Today’s installment concludes Wesley Begins Methodism,

our selection from History of England in the Eighteenth Century by William E.H. Lecky published in 1890.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Wesley Begins Methodism.

Time: 1738

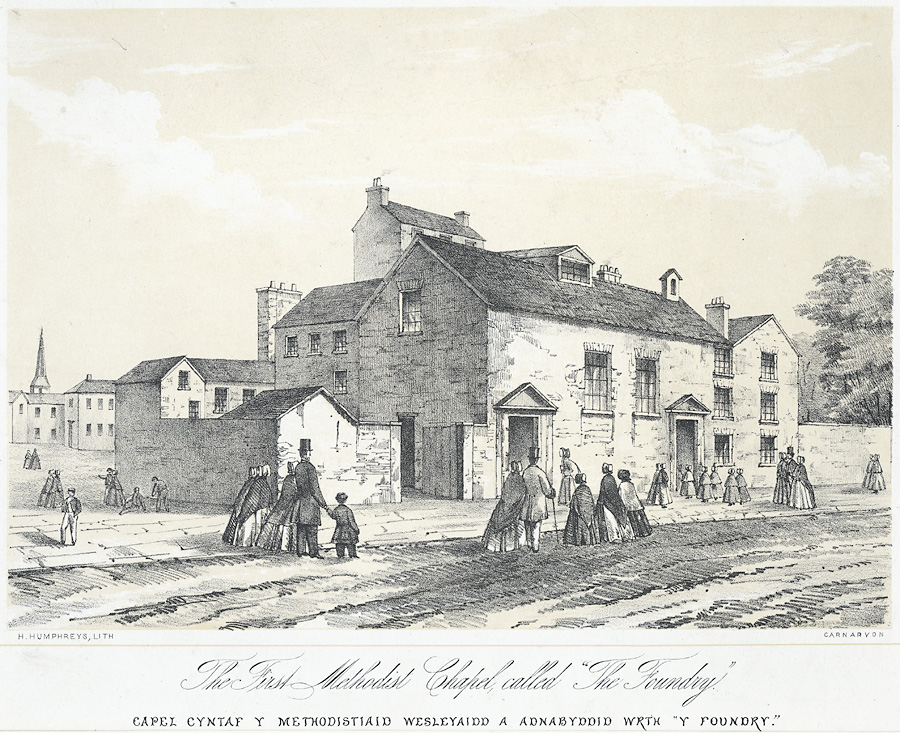

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

He was filled with horror and compassion at finding in the heart of a Christian country, and in the immediate neighborhood of a great city, a population of many thousands sunk in the most brutal ignorance and vice, and entirely excluded from the ordinances of religion. Moved by such feelings, he resolved to address the colliers in their own haunts. The resolution was a bold one, for field-preaching was then utterly unknown in England, and it needed no common courage to brave all the obloquy and derision it must provoke, and to commence the experiment in the center of a half-savage population.

Whitefield, however, had a just confidence in his cause and in his powers. Standing himself upon a hillside, he took for his text the first words of the Sermon which was spoken from the Mount, and he addressed with his accustomed fire an astonished audience of some two hundred men. The fame of his eloquence spread far and wide. On successive occasions five, ten, fifteen, even twenty thousand were present. It was February, but the winter sun shone clear and bright. The lanes were filled with the carriages of the more wealthy citizens, whom curiosity had drawn from Bristol. The trees and hedges were crowded with humbler listeners, and the fields were darkened by a compact mass. The face of the preacher paled with a thrilling power to the very outskirts of that mighty throng. The picturesque novelty of the occasion and of the scene, the contagious emotion of so great a multitude, a deep sense of the condition of his hearers and of the momentous importance of the step he was taking, gave an additional solemnity. His rude auditors were electrified. They stood for a time in rapt and motionless attention. Soon tears might be seen forming white gutters down cheeks blackened from the coal-mine. Then sobs and groans told how hard hearts were melting at his words. A fire was kindled among the outcasts of Kingswood, which burned long and fiercely, and was destined in a few years to overspread the land.

It was only with great difficulty that Whitefield could persuade the Wesleys to join him in this new phase of missionary labor. John Wesley has left on record, in his journal, his first repugnance to it, “having,” as he says, “been all my life (till very lately) so tenacious of every point relating to decency and order, that I should have thought the saving of souls almost a sin if it had not been done in a church.” Charles Wesley, on this as on most other occasions, was even more strongly conservative. The two brothers adopted their usual superstitious practice of opening their Bibles at random, under the belief that the texts on which their eyes first fell would guide them in their decision. The texts were ambiguous and somewhat ominous, relating for the most part to violent deaths; but on drawing lots the lot determined them to go. It was on this slender ground that they resolved to give the weight of their example to this most important development of the movement. They went to Bristol, from which Whitefield was speedily called, and continued the work among the Kingswood colliers and among the people of the city; while Whitefield, after a preaching tour of some weeks in the country, reproduced on a still larger scale the triumphs of Kingswood by preaching with marvelous effect to immense throngs of the London rabble at Moorfields and on Kennington Common. From this time field-preaching became one of the most conspicuous features of the revival.

The character and genius of the preacher to whom this most important development of Methodism was due demand a more extended notice than I have yet given them. Unlike Wesley, whose strongest enthusiasm was always curbed by a powerful will, and who manifested at all times and on all subjects an even exaggerated passion for reasoning, Whitefield was chiefly a creature of impulse and emotion. He had very little logical skill, no depth or range of knowledge, not much self-restraint, nothing of the commanding and organizing talent, and, it must be added, nothing of the arrogant and imperious spirit so conspicuous in his colleague. At the same time a more zealous, a more single-minded, a more truly amiable, a more purely unselfish man it would be difficult to conceive. He lived perpetually in the sight of eternity, and a desire to save souls was the single passion of his life. Of his labors it is sufficient to say that it has been estimated that in the thirty-four years of his active career he preached eighteen thousand times, or on an average ten times a week; that these sermons were delivered with the utmost vehemence of voice and gesture, often in the open air, and to congregations of many thousands; and that he continued his exertions to the last, when his constitution was hopelessly shattered by disease. During long periods he preached forty hours, and sometimes as much as sixty hours, a week. In the prosecution of his missionary labors he visited almost every important district in England and Wales. At least twelve times he traversed Scotland, three times he preached in Ireland, thirteen times he crossed the Atlantic.

Very few men placed by circumstances at the head of a great religious movement have been so absolutely free from the spirit of sect. Very few men have passed through so much obloquy with a heart so entirely unsoured, and have retained amid so much adulation so large a measure of deep and genuine humility. There was indeed not a trace of jealousy, ambition, or rancor in his nature. There is something singularly touching in the zeal with which he endeavored to compose the differences between himself and Wesley, when so many of the followers of each leader were endeavoring to envenom them; in the profound respect he continually expressed for his colleague at the time of their separation; in the exuberant gratitude he always showed for the smallest act of kindness to himself; in the tenderness with which he guarded the interests of the inmates of that orphanage at Georgia around which his strongest earthly affections were entwined; in the almost childish simplicity with which he was always ready to make a public confession of his faults.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Wesley Begins Methodism by William E.H. Lecky from his book History of England in the Eighteenth Century published in 1890. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Wesley Begins Methodism here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.