This series has six easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: The Moral Forces of the Great Religions.

Introduction

There were many reasons which led the populace to hate Christians, whom, first of all, they regarded as being unpatriotic. While among Romans it was considered the highest honor to possess the privileges of Roman citizenship, the Christians announced that they were citizens of heaven. They shrank from public office and military service.

Before the USA adopted the separation of church and state the predominant political philosophy was that religion was integral to the state and disloyalty to the state religion was disloyalty to the state. Even after the Renaissance in Christian Europe, religious wars between Protestants and Catholics engaged their civilization.

Again, the ancient religion of Rome was an adjunct of state dignity and ceremonial. It was hallowed by a thousand traditional and patriotic associations. The Christians regarded its rites and its popular assemblies with contempt and abhorrence. The Romans viewed the secret meetings of the Christians with suspicion, and accused them of abominable excesses and crime. They were known to have representatives in every important city of Gaul, Spain, Italy, and Asia; and the more their communities grew, the more the Roman populace raged against them. Only such considerations appear to mitigate the historical judgments against Aurelius for marring the splendor of his reign by persecutions. The tragedies enacted in the churches of Lyons and Vienne, as described in the following pages, form one of the most melancholy records of history.

This selection is from History of France by François P. G. Guizot published in 1875. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

He Guizot quotes extensively from Ecclesiastical History by Eusebius (260/265 – 339/340) in this series. Eusebius was a bishop who wrote a lot abut the Bible and church history.

François P. G. Guizot (1787-1874) was a dominant figure in French politics prior to the Revolution of 1848. His monumental History of France was used for many other series on this website.

Time: 177

Place: France

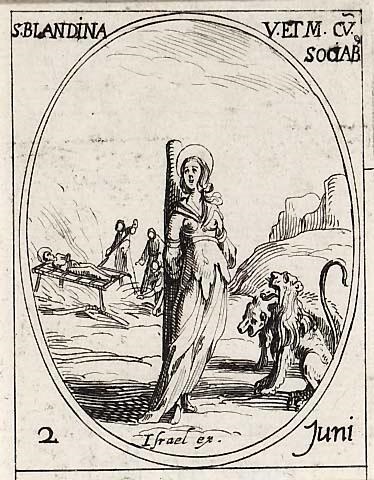

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

When Christianity began to penetrate into Gaul, it encountered there two religions very different one from the other, and infinitely more different from the Christian religion; these were Druidism and paganism — hostile one to the other, but with a hostility political only, and unconnected with those really religious questions that Christianity was coming to raise.

Druidism, considered as a religion, was a mass of confusion, wherein the instinctive notions of the human race concerning the origin and destiny of the world and of mankind were mingled with the oriental dreams of metempsychosis — that pretended transmigration, at successive periods, of immortal souls into divers creatures. This confusion was worse confounded by traditions borrowed from the mythologies of the East and the North, by shadowy remnants of a symbolical worship paid to the material forces of nature, and by barbaric practices, such as human sacrifices, in honor of the gods or of the dead.

People who are without the scientific development of language and the art of writing do not attain to systematic and productive religious creeds. There is nothing to show that, from the first appearance of the Gauls in history to their struggle with victorious Rome, the religious influence of Druidism had caused any notable progress to be made in Gallic manners and civilization. A general and strong, but vague and incoherent, belief in the immortality of the soul was its noblest characteristic. But with the religious elements, at the same time coarse and mystical, were united two facts of importance: the Druids formed a veritable ecclesiastical corporation, which had, throughout Gallic society, fixed attributes, special manners and customs, an existence at the same time distinct and national; and in the wars with Rome this corporation became the most faithful representatives and the most persistent defenders of Gallic independence and nationality.

The Druids were far more a clergy than Druidism was a religion; but it was an organized and a patriotic clergy. It was especially on this account that they exercised in Gaul an influence which was still existent, particularly in Northwestern Gaul, at the time when Christianity reached the Gallic provinces of the South and Center.

The Graeco-Roman paganism was, at this time, far more powerful than Druidism in Gaul, and yet more lukewarm and destitute of all religious vitality. It was the religion of the conquerors and of the State, and was invested, in that quality, with real power; but, beyond that, it had but the power derived from popular customs and superstitions. As a religious creed, the Latin paganism was at bottom empty, indifferent, and inclined to tolerate all religions in the State, provided only that they, in their turn, were indifferent at any rate toward itself, and that they did not come troubling the State, either by disobeying her rulers or by attacking her old deities, dead and buried beneath their own still standing altars.

Such were the two religions with which in Gaul nascent Christianity had to contend. Compared with them it was, to all appearance, very small and very weak; but it was provided with the most efficient weapons for fighting and beating them, for it had exactly the moral forces which they lacked. Christianity, instead of being, like Druidism, a religion exclusively national and hostile to all that was foreign, proclaimed a universal religion, free from all local and national partiality, addressing itself to all men in the name of the same God, and offering to all the same salvation. It is one of the strangest and most significant facts in history that the religion most universally human, most dissociated from every consideration but that of the rights and well-being of the human race in its entirety — that such a religion, be it repeated, should have come forth from the womb of the most exclusive, most rigorously and obstinately national religion that ever appeared in the world, that is, Judaism. Such, nevertheless, was the birth of Christianity; and this wonderful contrast between the essence and the earthly origin of Christianity was without doubt one of its most powerful attractions and most efficacious means of success.

Against paganism Christianity was armed with moral forces not a whit less great. Confronting mythological traditions and poetical or philosophical allegories, appeared a religion truly religious, concerned solely with the relations of mankind to God and with their eternal future. To the pagan indifference of the Roman world the Christians opposed the profound conviction of their faith, and not only their firmness in defending it against all powers and all dangers, but also their ardent passion for propagating it without any motive but the yearning to make their fellows share in its benefits and its hopes. They confronted, nay, they welcomed martyrdom, at one time to maintain their own Christianity, at another to make others Christians around them; propagandism was for them a duty almost as imperative as fidelity.

And it was not in memory of old and obsolete mythologies, but in the name of recent deeds and persons, in obedience to laws proceeding from God, One and Universal, in fulfilment and continuation of a contemporary and superhuman history — that of Jesus Christ, the Son of God and Son of Man — that the Christians of the first two centuries labored to convert to their faith the whole Roman world. Marcus Aurelius was contemptuously astonished at what he called the obstinacy of the Christians; he knew not from what source these nameless heroes drew a strength superior to his own, though he was at the same time emperor and sage. It is impossible to assign with exactness the date of the first footprints and first labors of Christianity in Gaul. It was not, however, from Italy, nor in the Latin tongue and through Latin writers, but from the East and through the Greeks, that it first came and began to spread. Marseilles and the different Greek colonies, originally from Asia Minor and settled upon the shores of the Mediterranean or along the Rhone, mark the route and were the places whither the first Christian missionaries carried their teaching: on this point the letters of the apostles and the writings of the first two generations of their disciples are clear and abiding proof.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.