Despite his vigor and his authority, Innocent’s constant interference with the internal concerns of every country in Europe did not pass unchallenged.

Continuing Zenith of Papal Power,

our selection from The Empire and the Papacy, 918-1273 by Thomas F. Tout published in 1908. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Zenith of Papal Power.

Time: 1208

Place: Vatican

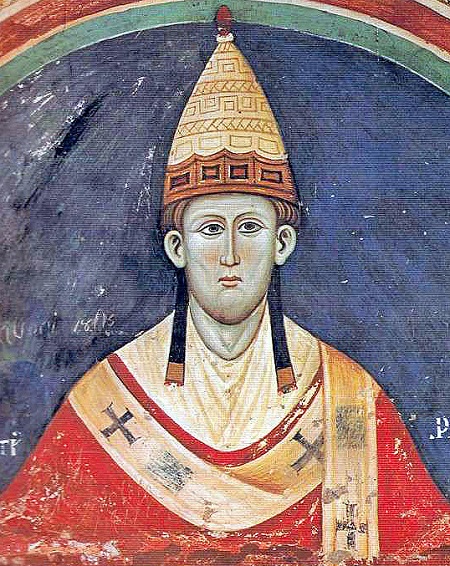

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The long strife of Innocent with John of Anjou, about the disputed election to the see of Canterbury, was fought with the same weapons which the Pope had already employed against the King of France. But John held out longer. Interdict was followed by excommunication and threatened deposition. At last the English King surrendered his crown to the papal agent Pandulf, and, like Peter of Aragon, received it back as a vassal of the papacy, bound by an annual tribute.

Nor were these the only kings that sought the support of the great Pope. The schismatic princes of the East vied in ardor with the Catholic princes of the West in their quest of Innocent’s favor. King Leo of Armenia begged for his protection. The Bulgarian prince John besought the Pope to grant him a royal crown. Innocent posed as a mediator in Hungary between the two brothers, Emeric and Andrew, who were struggling for the crown. Canute of Denmark, zealous for his sister’s honor, was his humble suppliant. Poland was equally obedient. The Duke of Bohemia accepted the papal reproof for allying himself with Philip of Swabia.

Despite his vigor and his authority, Innocent’s constant interference with the internal concerns of every country in Europe did not pass unchallenged. Even the kings who invoked his intercession were constantly in conflict with him. Besides his great quarrels in Germany, France, and England, Innocent had many minor wars to wage against the princes of Europe. For five years the kingdom of Leon lay under interdict because its king Alfonso had married his cousin, Berengaria of Castile, in the hope of securing the peace between the two realms. It was only after the lady had borne five children to Alfonso that she voluntarily terminated the obnoxious union, and Innocent found it prudent, as in France, to legitimize the offspring of a marriage which he had denounced as incestuous. Not one of the princes of the peninsula was spared. Sancho of Navarre incurred interdict by reason of suspected dealings with the Saracens, while the marriage of his sister with Peter of Aragon, the vassal of the Pope, involved both kings in a contest with Innocent. Not only did the monarchs of Europe resent, so far as they were able, the Pope’s haughty policy; for the first time the peoples of their realms began to make common cause with them against the political aggressions of the papacy. The nobles of Aragon protested against King Peter’s submission to the papacy, declared that his surrender of their kingdom was invalid, and prevented the payment of the promised tribute. When John of England procured his Roman overlord’s condemnation of Magna Charta, the support of Rome was of no avail to prevent his indignant subjects combining to drive him from the throne, and did not even hinder Louis of France, the son of the papalist Philip II, from accepting their invitation to become English king in his stead. It was only by a repudiation of this policy, and by an acceptance of the Great Charter, that the papacy could secure the English throne for John’s young son, Henry III, and thus continue for a time its precarious overlordship over England.

For the moment Innocent’s iron policy crushed opposition, but in adding the new hostility of the national kings and the rising nations of Europe to the old hostility of the declining empire, Innocent was entering into a perilous course of conduct, which, within a century, was to prove fatal to one of the strongest of his successors. The more political the papal authority became, the more difficult it was to uphold its prestige as the source of law, of morality, of religion. Innocent himself did not lose sight of the higher ideal because he strove so firmly after more earthly aims. His successors were not always so able or so high-minded. And it was as the protectors of the people, not as the enemies of their political rights, that the great popes of the eleventh and twelfth centuries had obtained their wonderful ascendency over the best minds of Europe.

The coronation of Otto IV did not end Innocent’s troubles with the Empire. It was soon followed by an open breach between the Pope and his nominee, from which ultimately developed something like a general European war, between a league of partisans of the Pope and a league of partisans of Otto. It was inevitable that Otto, as a crowned emperor, should look upon the papal power in a way very different from that in which he had regarded it when a faction leader struggling for the crown. Then the support of the Pope was indispensable. Now the autocracy of the Pope was to be feared. The Hohenstaufen ministeriales, who now surrounded the Guelfic Emperor, raised his ideals and modified his policy. Henry of Kalden, the old minister of Henry VI, was now his closest confidant, and under his direction it soon became Otto’s ambition to continue the policy of the Hohenstaufen. The great object of Henry VI had been the union of Sicily with the Empire. To the alarm and disgust of Innocent, his ancient dependent now strove to continue Henry VI’s policy by driving out Henry VI’s son from his Sicilian inheritance. Otto now established relations with Diepold and the other German adventurers, who still defied Frederick II and the Pope in Apulia. He soon claimed the inheritance of Matilda as well as the Sicilian monarchy. In August, 1210, he occupied Matilda’s Tuscan lands, and in November invaded Apulia, and prepared to dispatch a Pisan fleet against Sicily. Innocent was moved to a terrible wrath. On hearing of the capture of Capua, and the revolt of Salerno and Naples, he excommunicated the Emperor and freed his subjects from their oaths of fealty to him. But, despite the threats of the Church, Otto conquered most of Apulia and was equally successful in reviving the Imperial authority in Northern Italy.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.