Today’s installment concludes Zenith of Papal Power,

our selection from The Empire and the Papacy, 918-1273 by Thomas F. Tout published in 1908.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of seven thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Zenith of Papal Power.

Time: 1208

Place: Vatican

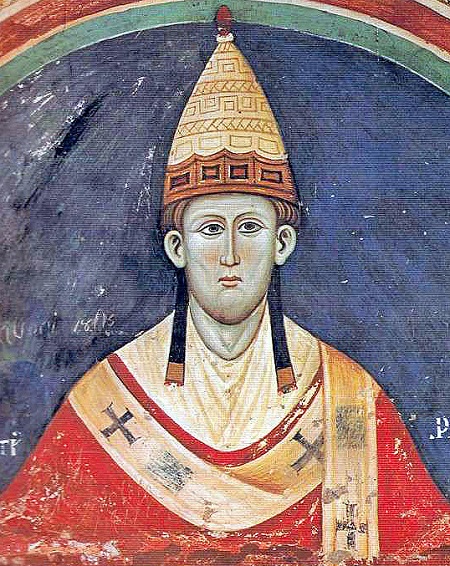

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Amid all the distractions of western politics, Innocent III ardently strove to revive the crusading spirit. He never succeeded in raising all Europe, as several of his predecessors had done. But after great efforts, and the eloquent preaching of Fulk of Neuilly he stirred up a fair amount of enthusiasm for the crusading cause, and, in 1204, a considerable crusading army, mainly French, mustered at Venice. It was the bitterest disappointment of Innocent’s life that the Fourth Crusade never reached Palestine, but was diverted to the conquest of the Greek empire. Yet the establishment of a Catholic Latin empire at Constantinople, at the expense of the Greek schismatics, was no small triumph. Not disheartened by his first failure, Innocent still urged upon Europe the need of the holy war. If no expedition against the Saracens of Syria marked the result of his efforts, his pontificate saw the extension of the crusading movement to other lands. Innocent preached the crusade against the Moors of Spain, and rejoiced in the news of the momentous victory of the Christians at Navas de Tolosa. He saw the beginnings of a fresh crusade against the obstinate heathen on the eastern shores of the Baltic.

But all these crusades were against pagans and infidels. Innocent made a much greater new departure when he proclaimed the first crusade directed against a Christian land. The Albigensian crusade succeeded in destroying the most dangerous and widespread popular heresy that Christianity had witnessed since the fall of the Roman Empire, and Innocent rejoiced that his times saw the Church purged of its worst blemish. But in extending the benefits of a crusade to Christians fighting against Christians, he handed on a precedent which was soon fatally abused by his successors. In crushing out the young national life of Southern France the papacy again set a people against itself. The denunciations of the German Minnesinger were reechoed in the complaints of the last of the Troubadours. Rome had ceased to do harm to Turks and Saracens, but had stirred up Christians to war against fellow-Christians. God and his saints abandon the greedy, the strife-loving, the unjust worldly Church. The picture is darkly colored by a partisan, but in every triumph of Innocent there lay the shadow of future trouble.

Crusades, even against heretics and infidels, are the work of earthly force rather than of spiritual influence. It was to build up the great outward corporation of the Church that all these labors of Innocent mainly tended. Even his additions to the canon law, his reforms of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, dealt with the external rather than the internal life of the Church. The criticism of James of Vitry, that the Roman curia was so busy in secular affairs that it hardly turned a thought to spiritual things, is clearly applicable to much of Innocent’s activity. But the many-sided Pope did not ignore the religious wants of the Church. His crusade against heresy was no mere war against enemies of the wealth and power of the Church. The new tendencies that were to transform the spiritual life of the thirteenth century were not strange to him. He favored the early work of Dominic; he had personal dealings with Francis, and showed his sympathy with the early work of the poor man of Assisi. But it is as the conqueror and organizer rather than the priest or prophet that Innocent made his mark in the Church. It is significant that, with all his greatness, he never attained the honors of sanctity.

Toward the end of his life, Innocent held a general council in the basilica of St. John Lateran. A vast gathering of bishops heads of orders, and secular dignitaries gave brilliancy to the gathering and enhanced the glory of the Pontiff. Enthroned over more than four hundred bishops, the Pope proudly declared the law to the world. “Two things we have specially to heart,” wrote Innocent, in summoning the assembly, “the deliverance of the Holy Land and the reform of the Church Universal.” In its vast collection of seventy canons, the Lateran Council strove hard to carry out the Pope’s program. It condemned the dying heresies of the Albigenses and the Cathari, and prescribed the methods and punishments of the unrepentant heretic. It strove to rekindle zeal for the crusade. It drew up a drastic scheme for reforming the internal life and discipline of the Church. It strove to elevate the morals and the learning of the clergy, to check their worldliness and covetousness, and to restrain them from abusing the authority of the Church through excess of zeal or more corrupt motives. It invited bishops to set up free schools to teach poor scholars grammar and theology. It forbade trial by battle and trial by ordeal. It subjected the existing monastic orders to stricter superintendence, and forbade the establishment of new monastic rules. It forbade superstitious practices and the worship of spurious or unauthorized relics.

The whole series of canons sought to regulate and ameliorate the influence of the Church on society. If many of the abuses aimed at were too deeply rooted to be overthrown by mere legislation, the attempt speaks well for the character and intelligence of Pope and council. All mediaeval lawmaking, civil and ecclesiastical alike, was but the promulgation of an ideal, rather than the issuing of precepts meant to be literally executed. But no more serious attempt at rooting out inveterate evils was ever made in the Middle Ages than in this council.

The formal enunciation of this lofty program of reform brought Innocent’s pontificate to a glorious end. The Pontiff devoted what little remained of his life to hurrying on the preparations for the projected crusade, which was to set out 1217. But in the summer of 1216 Innocent died at Perugia, when only fifty-six years old. If not the greatest he was the most powerful of all the popes. For nearly twenty years the whole history of Europe groups itself round his doings.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Zenith of Papal Power by Thomas F. Tout from his book The Empire and the Papacy, 918-1273 published in 1908. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Zenith of Papal Power here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.