For the first time, a German national irritation at the aggressions of the papacy began to be distinctly felt.

Continuing Zenith of Papal Power,

our selection from The Empire and the Papacy, 918-1273 by Thomas F. Tout published in 1908. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Zenith of Papal Power.

Time: 1208

Place: Vatican

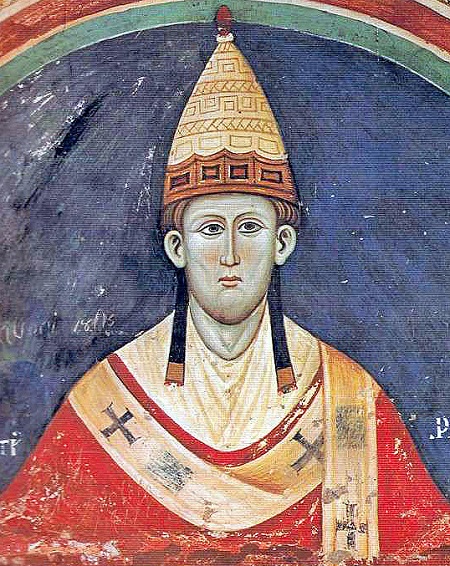

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Innocent saw the power that he had built up so carefully in Italy crumbling rapidly away. In his despair he turned to France and Germany for help against the audacious Guelf. Philip Augustus, though still in bad odor at Rome through his persistent hostility to Ingeborg, was now an indispensable ally. He actively threw himself into the Pope’s policy, and French and papal agents combined to stir up disaffection against Otto in Germany. The haughty manners and the love of the young King for Englishmen and Saxons had already excited disaffection. It was believed that Otto wished to set up a centralized despotism of court officials, levying huge taxes on the model of the Angevin administrative system of his grandfathers and uncles. The bishops now took the lead in organizing a general defection from the absent Emperor. In September, 1211, a gathering of disaffected magnates, among whom were the newly made king Ottocar of Bohemia and the dukes of Austria and Bavaria, assembled at Nuremberg. They treated the papal sentence as the deposition of Otto, and pledged themselves to elect as their new king Frederick of Sicily, the sometime ward of the Pope. It was not altogether good news to the Pope that the German nobles had, in choosing the son of Henry VI, renewed the union of German and Sicily. But Innocent felt that the need of setting up an effective opposition to Otto was so pressing that he put out of sight the general in favor of the immediate interests of the Roman see. He accepted Frederick as emperor, only stipulating that he should renew his homage for the Sicilian crown, and consequently renounce an inalienable union between Sicily and the Empire. Frederick now left Sicily, repeated his submission to Innocent at Rome, and crossed the Alps for Germany.

Otto had already abandoned Italy to meet the threatened danger in the North. Misfortunes soon showered thick upon him. His Hohenstaufen wife, Beatrice, died, and her loss lessened his hold on Southern Germany. When Frederick appeared, Swabia and Bavaria were already eager to welcome the heir of the mighty southern line, and aid him against the audacious Saxon. The spiritual magnates flocked to the side of the friend and pupil of the Pope. In December, 1212, followed Frederick’s formal election and his coronation at Mainz by the archbishop Siegfried. Early in 1213 Henry of Kalden appeared at his court. Henceforward the important class of the ministeriales was divided. While some remained true to Otto, others gradually went back to the personal representative of Hohenstaufen.

Otto was now thrown back on Saxony and the Lower Rhineland. He again took up his quarters with the faithful citizens of Cologne, when he appealed for help to his uncle, John of England, still under the papal ban. With English help he united the princes of the Netherlands in a party of opposition to the Pope and the Hohenstaufen. Frederick answered by a closer and a more effective league with France. Even before his coronation he had met Louis, the son of Philip Augustus, at Vaucouleurs. All Europe seemed arming at the bidding of the Pope and Emperor.

John of England now hastily reconciled himself to Innocent, at the price of the independence of his kingdom. He thus became in a better position to aid his excommunicated nephew, and revenge the loss of Normandy and Anjou on Philip Augustus. His plan was now a twofold one. He himself summoned the barons of England to follow him in an attempt to recover his ancient lands on the Loire. Meanwhile, Otto and the Netherlandish lords were encouraged, by substantial English help, to carry out a combined attack on France from the north. The opposition of the English barons reduced to comparative insignificance the expedition to Poitou, but a very considerable army gathered together under Otto, and took up its position in the neighborhood of Tournai. Among the French King’s vassals, Ferrand, Count of Flanders, long hostile to his overlord Philip, and the Count of Boulogne fought strenuously on Otto’s side; while, of the Imperial vassals, the Count of Holland and Duke of Brabant (Lower Lorraine) were among Otto’s most active supporters. A considerable English contingent came also, headed by Otto’s bastard uncle, William Longsword, Earl of Salisbury. Philip himself commanded the chivalry of France, leaving his son Louis to fight against John in Poitou. On July 27th the decisive battle was fought at Bouvines, a few miles southwest of Tournai. The army of France and Church gained an overwhelming victory over the league which had incurred the papal ban, and Otto’s fortunes were utterly shattered. He soon lost all his hold over the Rhineland, and was forced to retreat to the ancient domains of his house in Saxony. His remaining friends made their peace with Philip and Frederick. The defection of the Wittelsbachers lost his last hold in the south of Germany, and the desertion of Valdemar of Denmark deprived him of a strong friend in the North. John withdrew from Continental politics to be beaten more decisively by his barons than he had been beaten in Poitou or at Bouvines.

Frederick II, was now undisputed King of the Romans, and Innocent III had won another triumph. By the Golden Bull of Eger (July, 1213) Frederick had already renewed the concessions made by Otto to the Church, and promised obedience to the holy see. In 1216 he pledged himself to separate Sicily from the Empire, and establish his son Henry there as king, under the supremacy of the Church. But, like his other triumphs, Innocent’s victory over the Empire was purchased at no small cost. For the first time, a German national irritation at the aggressions of the papacy began to be distinctly felt. It found an adequate expression in the indignant verses of Walther von der Vogelweide, protesting against the priests who strove to upset the rights of the laity, and denouncing the greed and pride of the foreigners who profited by the humiliation of Germany.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.