He wrote, ”The settlement of this matter belongs to the apostolic see, mainly because it was the apostolic see that transferred the Empire from the East to the West, and ultimately because the same see confers the Imperial crown.”

Continuing Zenith of Papal Power,

our selection from The Empire and the Papacy, 918-1273 by Thomas F. Tout published in 1908. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Zenith of Papal Power.

Time: 1208

Place: Vatican

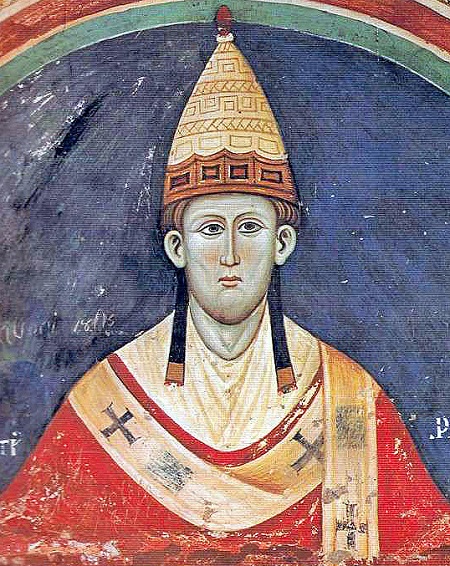

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Despite the precautions taken by Henry VI, it was soon clear that the German princes would not accept the hereditary rule of a child of three. Philip of Swabia abandoned his Italian domains and hurried to Germany, anxious to do his best for his nephew. But he soon perceived that Frederick’s chances were hopeless, and that it was all that he could do to prevent the undisputed election of a Guelf. He was favored by the absence of the two elder sons of Henry the Lion. Henry of Brunswick the eldest, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, was away on a crusade, and was loyal to the Hohenstaufen, since his happy marriage with Agnes. The next son Otto, born at Argenton during his father’s first exile, had never seen much of Germany. Brought up at his uncle Richard of Anjou’s court, Otto had received many marks of Richard’s favor, and looked up to the chivalrous, adventurous King as an ideal of a warrior prince. Richard had made him Earl of Yorkshire, and had invested him in 1196 with the country of Poitou, that he might learn war and statecraft in the same rude school in which Richard had first acquainted himself with arms and politics. Even now Otto was not more than seventeen years of age. Richard himself, as the new vassal of the Empire for Aries and England, was duly summoned to the electoral diet, but his representatives impolitically urged the claims of Count Henry, who was ruled ineligible on account of his absence. Thus it was that when the German magnates at last met for the election on the 8th of March, 1198, at Muehlhausen, their choice fell on Philip the Arabian, who took the title of Philip II.

Many of the magnates had absented themselves from the diet at Muehlhausen, and an irreconcilable band of partisans refused to be bound by its decisions. Richard of England now worked actively for Otto, his favorite nephew, and found support both in the old allies of the Angevins in the Lower Rhineland and the ancient supporters of the house of Guelf. Germany was thus divided into two parties, who completely ignored each other’s acts. Three months after the diet of Muehlhausen, another diet met at Cologne and chose Otto of Brunswick as King of the Romans. Three days afterward the young prince was crowned at Aachen.

A ten-years’ civil war between Philip II and Otto IV now devastated the Germany that Barbarossa and Henry VI had left so prosperous. The majority of the princes remained firm to Philip, who also had the support of the strong and homogeneous official class of ministeriales that had been the best helpers of his father and brother. Nevertheless, Otto had enough of a party to carry on the struggle. On his side was Cologne, the great mart of Lower Germany, so important from its close trading relations with England, and now gradually shaking itself free of its archbishops. The friendship of Canute of Denmark and the Guelf tradition combined to give him his earliest and greatest success in the North. It was the interest of the baronage to prolong a struggle which secured their own independence at the expense of the central authority. Both parties looked for outside help. Otto, besides his Danish friends, relied on his uncle Richard, and, after his death, on his uncle John. Philip formed a league with his namesake Philip of France. But distant princes could do but little to determine the result of the contest. It was of more moment that both appealed to Innocent III, and that the Pope willingly accepted the position of arbiter. “The settlement of this matter,” he declared, “belongs to the apostolic see, mainly because it was the apostolic see that transferred the Empire from the East to the West, and ultimately because the same see confers the Imperial crown.”

In March, 1201, Innocent issued his decision. “We pronounce,” he declared, “Philip unworthy of empire, and absolve all who have taken oaths of fealty to him as king. Inasmuch as our dearest son in Christ, Otto, is industrious, discreet, strong, and constant, himself devoted to the Church and descended on each side from a devout stock, we, by the authority of St. Peter, receive him as king, and will in due course bestow upon him the imperial crown.” The grateful Otto promised in return to maintain all the possessions and privileges of the Roman Church, including the inheritance of the countess Matilda.

Philip of Swabia still held his own, and the extravagance of the papal claim led to many of the bishops as well as the lay magnates of Germany joining in a declaration that no former pope had ever presumed to interfere in an imperial election. But the swords of his German followers were a stronger argument in favor of Philip’s claims than the protests of his supporters against papal assumptions. As time went on, the Hohenstaufen slowly got the better of the Guelfs. With the falling away of the North, Otto’s cause became distinctly the losing one. In 1206, Otto was defeated outside the walls of Cologne, and the great trading city was forced to transfer its obedience to his rival. In 1207 Philip became so strong that Innocent was constrained to reconsider his position, and suggested to Otto the propriety of renouncing his claims. But in June, 1208, Philip was treacherously murdered at Bamberg by his faithless vassal, Otto of Wittelsbach, to whom he had refused his daughter’s hand. It was no political crime, but a deed of private vengeance. It secured, however, the position of Otto, for the ministeriales now transferred their allegiance to him, and there was no Hohenstaufen candidate ready to oppose him. Otto, moreover, did not scruple to undergo a fresh election which secured for him universal recognition in Germany. By marrying Beatrice, Philip of Swabia’s daughter, he sought to unite the rival houses, while he conciliated Innocent by describing himself as King “by the grace of God and the Pope.” Next year he crossed the Alps to Italy, and bound himself by oath, not only to allow the papacy the privileges that he had already granted, but to grant complete freedom of ecclesiastical elections, and to support the Pope in his struggle against heresy. In October, 1209, he was crowned Emperor at Rome. After ten years of waiting, Innocent, already master of Italy, had procured for his dependent both the German kingdom and the Roman Empire.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.