But the reader may naturally ask : “How can Mr. Burbank, or any other human being, cause nuts to thicken or thin their shells at his bidding?”

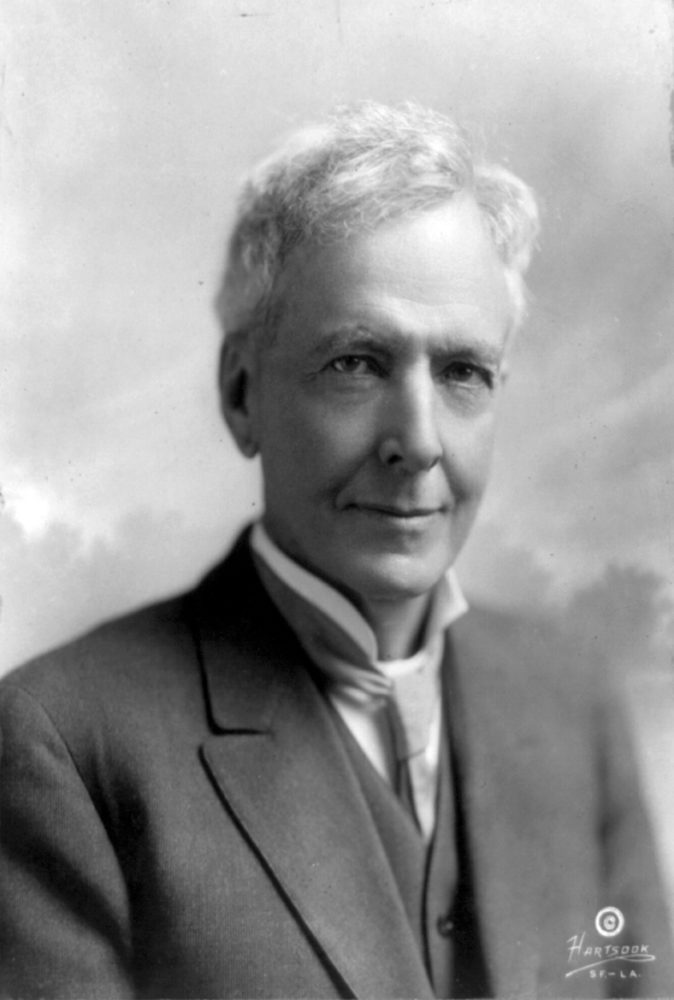

Continuing Luther Burbank’s Accomplishments,

with a selection from an article in Cosmopolitan Magazine by Garrett P. Servtss. This selection is presented in 4.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Luther Burbank’s Accomplishments.

Place: Santa Rosa, California

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

There appears to be no detail in the life and growth of plants that is beyond the reach of human interference and that can not be made to follow the dictates of man’s wishes. Once in a while Mr. Burbank discovers that he has gone too far, and that there is a wisdom garnered from ages of experience in some of nature’s arrangements which can not be violated with impunity. If nuts had thinner shells, for instance, it would be possible to dispense with nut-crackers. Accordingly Mr. Burbank once bred the shells of English walnuts so thin that they were easily broken. This proved a great boon to the birds, and they quickly got all the nuts, for they were up first in the morning and had to waste no time in climbing or shaking trees. So the process was reversed and the nuts were bred back again into the protection of thick shells. A similar thing happened when Mr. Burbank bred the prickly husks off chestnuts. He found that that kind of chestnuts would only answer for a birdless land, and he had to put the burrs on again. Nature has spent countless thousands of years in bringing about some of these adjustments of conditions to environment, which man can upset in a season or two if he finds it to his advantage to do so.

But the reader may naturally ask : “How can Mr. Burbank, or any other human being, cause nuts to thicken or thin their shells at his bidding?”

The answer sounds somewhat paradoxical : “He can do it because the world is so very old and so very full of life.”

In the eons of its past existence the kingdom of plants has stored up innumerable impressions derived from its ever changing environments. These impressions have produced hereditary tendencies ( tendencies toward their own perpetuation ) the greater number of which remain latent, and at present invisible, like photographic negatives not yet dipped into the developing-tray. There is not room enough in the whole world for all to manifest themselves simultaneously. If they were all materialized at once, a thousand earths would not suffice to hold the countless forms that are locked up, unseen, in plants. Only those are visible about us which have found favoring circumstances, and which upon the whole are best fitted for their present environments. But the latent tendencies, though held back, are not destroyed or obliterated. They are like so many memories stamped upon the brain, covered up under a flood of later impressions, apparently forgotten, yet ready, when the mystic chord is touched, to spring into vivid prominence. Thus it happens that through some change of environment, of food, soil, or climate, a concealed hereditary tendency, the sleeping memory of some former state of existence, awakes in a plant, and what the gardener or the horticulturist calls a “sport” is produced. The plant affected becomes like a black sheep in a snowy flock. It has heard a far-off ancestral voice and started backward at the call.

Now, ordinarily, these natural sports and variations are short-lived. There is no room or place for them in the existing order of things; they are not armed to engage in the struggle for existence; they are not “fitted” to survive; the favoring circumstance that brought them forth was but a flitting gleam, and with its departure they are left unsupported.

Yet here intelligence sees its opportunity to interfere. Man can govern the environment for the plant. He can re move unfriendly circumstances, and can eliminate the struggle for existence. Under his fostering care the exceptional plant, which has harked back to ancient traditions of its race, and assumed a form strange to its contemporaries, may be encouraged, stimulated, and developed until it becomes an established species.

Thus when Mr. Burbank crosses two species of walnuts and plants the new nuts so produced, the seedlings that spring up, are absolutely amazing in the variety of forms that they exhibit. The leaves of some resemble those of one parent, the leaves of others resemble those of the other parent; still others have leaves of an entirely novel and unexpected shape, not only imitating every known, and apparently every possible, type of walnut foliage, but even aping the foliage of the oak or the leaves of berry-bearing shrubs!

And all this is the result of a simple crossing of life-currents, in which these tendencies would have remained latent but for such crossing.

First crossing, to secure variation and break up established habits; then selection, to isolate and develop the new forms in which the master’s eye sees the indications of future useful ness, beauty, and permanence — such is the formula for the transformation of the plant-world, whose beginnings have drawn all eyes upon Luther Burbank.

After all, there is some verisimilitude in likening his operations to those of a wizard. The old magicians could not always foresee what spirits their necromancy would call forth and no more can this modern conjurer of science. We have seen that by crossing a raspberry with a blackberry he produced a valuable new species of fruit. But when he crossed the raspberry and the strawberry, a strange thing was summoned into existence a plant without the thorns of the rasp berry, but with the leaves and stolons of the strawberry, shooting up canes to the height of a man’s shoulder, bursting into an astonishing bloom of flowers such as neither the straw berry nor the raspberry plant ever knows, and finally, after this brilliant preparation, producing instead of berries, insignificant, unmaturing knobs!

Then he boldly crossed the blackberry with the apple. One can imagine what a successful combination of those species into an entirely new fruit might have meant. The result, however, was a plant, sprouting from blackberry seeds, that resembled a little apple-tree in foliage and growth, having no thorns and putting forth beautiful rose-colored flowers; but, alas! no fruit.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Garrett P. Servtss begins here. David Starr Jordan begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.