This is the second half of The Founding of Montreal

our selection from Villemarie by Alfred Sandham.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Founding of Montreal.

Time: 1642

Place: Isle de Montreal

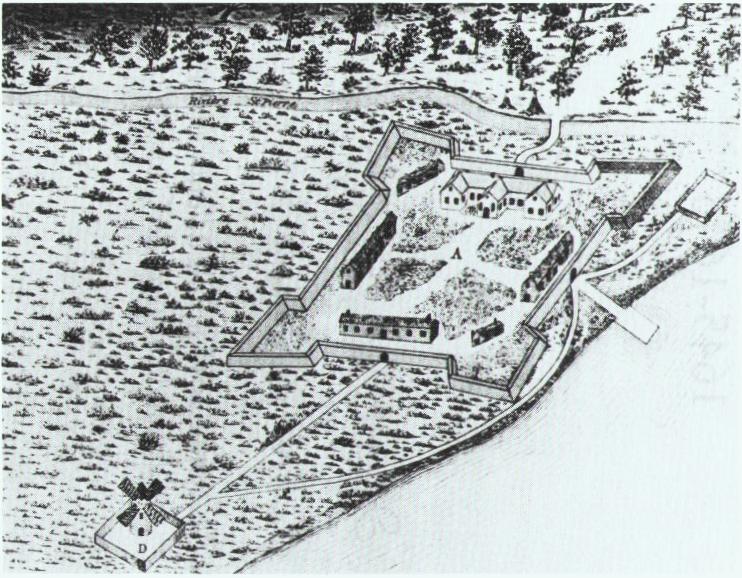

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Maisonneuve sprang ashore and fell on his knees. His followers imitated his example; and all joined their voices in songs of thanksgiving. Tents, baggage, arms, and stores were landed. Here were the ladies with their servants; Montmagny, no willing spectator; and Maisonneuve, a warlike figure, erect and tall, his men clustering around him–soldiers, sailors, artisans, and laborers–all alike soldiers at need. They kneeled in reverent silence as the host was raised aloft; and when the rite was over the priest turned and addressed them: “You are a grain of mustard-seed that shall rise and grow until its branches overshadow the land. You are few, but your work is the work of God. His smile is on you, and your children shall fill the land.” Then they pitched their tents, lighted their fires, stationed their guards, and lay down to rest. Such was the birthnight of Montreal. The following morning they proceeded to form their encampment, the first tree being felled by Maisonneuve. They worked with such energy that by the evening they erected a strong palisade, and had covered their altar with a roof formed of bark. It was some time after their arrival before their enemies, the Indians, were made aware of it, and they improved the time by building some substantial houses and in strengthening their fortifications.

The activity and zeal of Maisonneuve induced him to make a voyage to France to obtain assistance for his settlement. Though his difficulties were great, he yet was enabled to induce one hundred men to join his little establishment on the island. Notwithstanding this addition to his force, the progress of the colony was greatly retarded by the frequent attacks of the Indians. These enemies soon became a cause of great trouble to the colonists, and it was dangerous to pass beyond the palisades, as the Indians would hide for days, waiting to assail any unfortunate straggler. Although Maisonneuve was brave as man could be, he knew that his company was no match for the wily enemy, owing to their ignorance of the mode of Indian warfare; therefore he kept his men as near the fort as possible. They, however, failed to appreciate his care of them, and imputed it to cowardice. This led him to determine that such a feeling should not exist if he could possibly remove it. He therefore ordered his men to prepare to attack the Indians, at the same time signifying his intention to lead them himself. He sallied forth at the head of thirty men, leaving D’Aillebout with the remainder to hold the fort. After they had waded through the snow for some distance they were attacked by the Iroquois, who killed three of his men and wounded several others. Maisonneuve and his party held their ground until their ammunition began to fail, and then he gave orders to retreat, he himself remaining till the last. The men struggled on for some time facing the enemy, but finally they broke their ranks and retreated in great disorder toward the fort. Maisonneuve, with a pistol in each hand, held the Iroquois in check for some time. They might have killed him, but they wished to take him prisoner. Their chief, desiring this honor, rushed forward, but just as he was about to grasp him Maisonneuve fired and he fell dead. The Indians, fearing that the body of their chief would fall into the hands of the French, rushed forward to secure it, and Maisonneuve passed safely into the fort. From that day his men never dared to impute cowardice to him.

In 1644 the island of Montreal was made over to the Sulpicians of Paris, and was destined for the support of that religious order. In 1658 Viscount d’Argenson was appointed governor of Canada, but the day he landed the Iroquois murdered some Algonquin Indians under the very guns of Quebec. The Indians seemed determined to exterminate the French. In addition to keeping Quebec in a state little short of actual siege, they massacred a large number of the settlers at Montreal. D’Argenson having resigned, the Baron d’Avagnon was appointed governor (1661), and on his arrival visited the several settlements throughout the country. He was surprised to find them in such a deplorable condition, and made such representation to the King, as to the neglect of the Company of One Hundred Associates, that M. de Monts, the King’s commissioner, was ordered to visit Canada and report on its condition. At the same time four hundred more troops were added to the colonial garrison. The arrival of these troops gave life and confidence to the colonists and relieved Montreal from its dangers. The representations made by M. de Monts, as well as those of the Bishop of Quebec, determined Louis XIV to demand their charter from the Company of One Hundred Associates and to place the colony in immediate connection with the crown. As the profits of the fur trade had been much diminished by the hostility of the Iroquois, the company readily surrendered its privileges. As soon as the transfer was completed, D’Avagnon was recalled and M. de Mesy was appointed governor for three years. Canada was thus changed into a royal government, and a council of state was nominated to cooperate with the Governor in the administration of affairs. This council consisted of the Governor, the Bishop of Quebec, and the intendant, together with four others to be named by them, one of whom was to act as attorney-general.

| <—Previous | Master List |

More information on The Founding of Montreal here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.