Instead of attacking first the Serbians and then the Greeks and overwhelming them separately, it was necessary to fight their combined forces.

Continuing The Second Balkan War,

with a selection from The Balkan Question by Stephen P. Duggan. This selection is presented in 4.5 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Second Balkan War.

Time: 1913

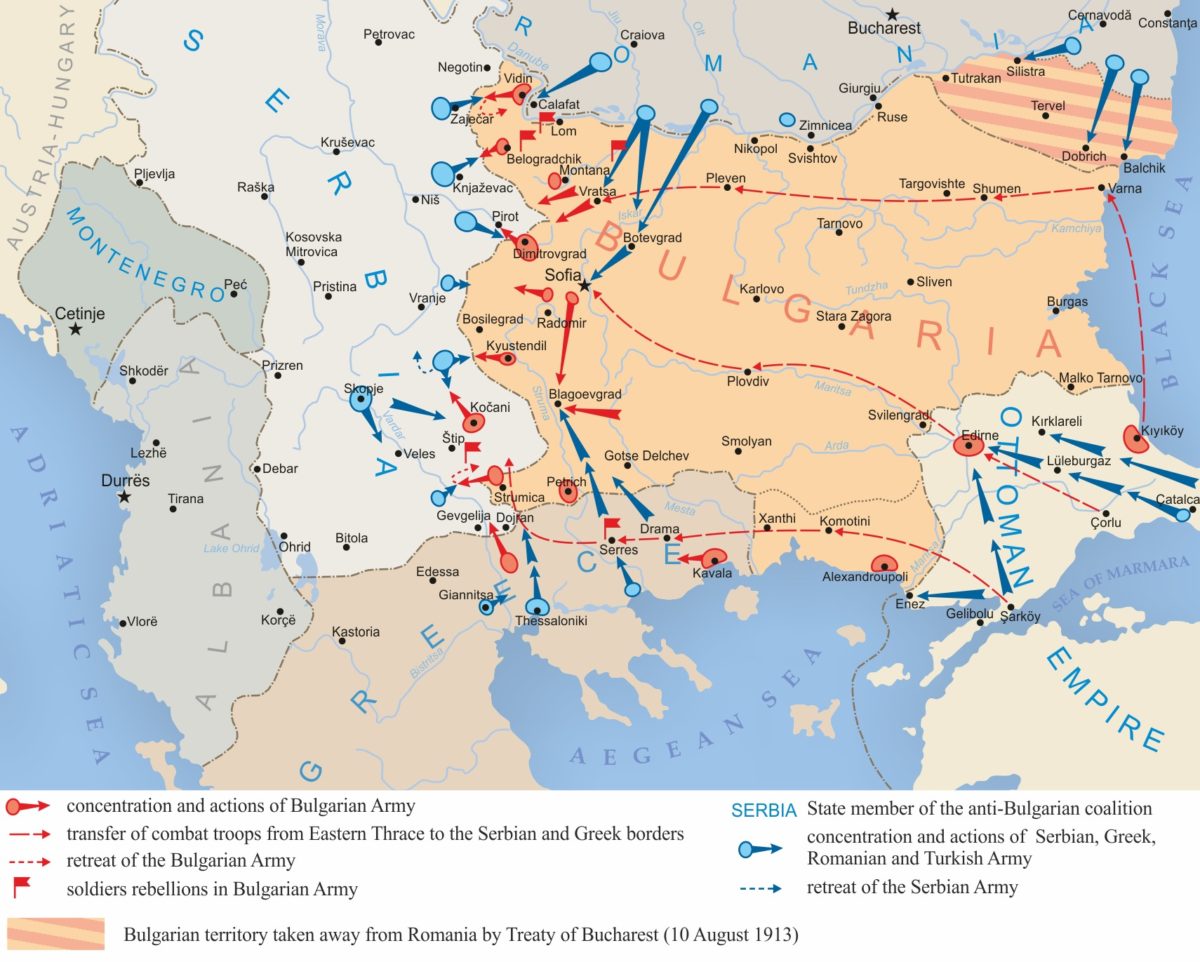

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

It was in his relations with Romania that Daneff’s diplomacy was most stupid. M. Take Jonescu, one of Romanians ablest statesmen, was sent by the Government to the first Peace Conference at London to secure pledges from Dr. Daneff in regard to the Romanian demand. He could get no answer. Daneff used every device to gain time in the hope that a settlement with Turkey would relieve Bulgaria from the necessity of giving anything. When the peace negotiations failed and the war between the allies and Turkey recommenced, the relations between Romania and Bulgaria became very critical. However, at the Czar’s suggestion, both countries agreed to refer the dispute to a conference of the ambassadors of the great Powers at St. Petersburg. Dr. Daneff, who represented Bulgaria, adopted a most truculent attitude and refused to yield on any point. As a result of the skilful diplomacy of the French ambassador, M. Delcassé, in reconciling the divergent views of the great Powers, Romania was awarded, on April 19th, the town of Silistria and a three-mile zone around it but was refused an increase on the seaboard. The award was very unpopular in Romania, but M. Jonescu risked his official life by successfully urging the Romanian Government to accept it. But when it became perfectly evident, after the signing of the Treaty of London on May 30th, that the former allies were now to be enemies, the Romanian government notified Bulgaria that she could not rely upon its neutrality without compensation in the interests of the equilibrium of the Balkans.

Such was the diplomatic situation when the Czar’s telegram of June 11th was received by King Ferdinand. Nothing could have been more inopportune for the Bulgarian cause. Though the government had no intention of changing its plan, sufficient deference had to be paid to the Czar’s request to suspend the forward movement of troops. The delay was fatal. The Serbians, who were already aware that the Bulgarians were in motion, now learned their direction and their actual positions. The Serbian Government hastened to fortify the passes of the Balkans between Bulgaria and the home territory, and the Serbian army in Macedonia effected a junction with the Greek army from Salonika. There was nothing left for the Bulgarians but to direct their offensive movements against the southern Serbian divisions in Macedonia. The great coup had failed. Instead of attacking first the Serbians and then the Greeks and overwhelming them separately, it was necessary to fight their combined forces.

Every element in the situation demanded the utmost caution on the part of Bulgaria. Elementary prudence dictated that she yield to Romanians demand for a slice of the seaboard to Baltchik in order to prevent Romania from joining Serbia and Greece. No doubt, had Daneff yielded he would have been voted out of office by the opposition, for the military party was in the ascendant at Sofia also. But a real statesman would not have flinched. Seldom has the influence of home politics upon the foreign affairs of a State operated so disastrously upon both. It was determined to carry out that part of the original plan of campaign which called for a surprise attack upon the Serbians. It must be remembered that all the engagements that had hitherto taken place between the former allies had been unofficial, Daneff all the while insisting that there existed no war, but “only military action to enforce the Serbo-Bulgarian treaty.” Nevertheless, on June 29th the word went forth from Bulgarian headquarters for a general attack upon the Serbian line which, taken by surprise, yielded.

In the mean time public opinion at Bucharest became almost uncontrollable in its demand for the mobilization of the troops, and the government was outraged at the continued prohibition by Russia of a forward movement. The Romanian Government had already appealed to Count Berchtold for Austro-Hungarian support against Russian interference, but Austria-Hungary, like every other great power, expected Bulgaria to win, and she intended that Bulgaria should take the place vacated by Turkey as a counterpoise to Russia in the Balkans. Hence Count Berchtold informed Romania that she could not rely upon Austro-Hungarian support, were she to ignore the Russian veto. But in the mean time an exaggerated report of the Serbian defeat had reached St. Petersburg on July 1st, and to save Serbia, Russia lifted the embargo on Romanian action.

Forty-eight hours later Europe knew that the Greeks had fought the fearful battle of Kilchis, resulting in the utter rout of the Bulgarians, who were in full retreat to defend the Balkan passes into their home territory. Russia at once recalled her permission for Romanian mobilization, but it was too late. The army was on the march.

The situation of Bulgaria was now truly desperate. Not only had her coup against the Serbians failed, but her troops were fleeing before the victorious Greeks up the Struma valley. On July 5th war was officially recognized by the withdrawal of the representatives of Greece, Montenegro, and Romania, from Sofia. On the same day Turkey requested the withdrawal of all Bulgarian troops east of the Enos-Midia line. In the bloody battles which continued to be fought against Greeks and Serbians, the Bulgarians were nearly everywhere defeated, and on July 10th Bulgaria placed herself unreservedly in the hands of Russia with a view to a cessation of hostilities.

This did not, however, prevent the forward movement of all her enemies. On July 15th, Turkey, “moved by the unnatural war” existing in the Balkan Peninsula, dispatched Enver Bey with an army to Adrianople, which he reoccupied July 20th. By that time the Romanians were within twenty miles of Sofia, and the guns of the Serbians and Greeks could be heard in the Bulgarian capital. The next day King Ferdinand telegraphed to King Charles of Romania, asking him to intercede with the kings of Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro. He did so, and all the belligerents agreed to send peace delegates to Bucharest. They assembled there on July 29th and at once concluded an armistice.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Stephen P. Duggan begins here. Capt. A.H. Trapmann begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.