This series has eight easy 5-minute installments. This first installment: Outbreak of Hostilities.

Introduction

The crushing defeat of Turkey by the Balkan States during the winter of 1912-13 had been accomplished mainly by Bulgaria. The Bulgarians were therefore eager to assert themselves as the chief Balkan State, the Power which was to take the place of Turkey as ruler of the “Near East.” Naturally this roused the antagonism not only of Bulgaria’s recent allies, Greece and Serbia, but also of the other neighboring State, Romania. Bulgaria hoped to meet and crush her two allies before Romania could join them. Thus, she deliberately precipitated a war which resulted in her utter defeat.

To understand this war, it should be realized that the Bulgars are really an Asiatic race, who broke into Europe as the Hungarians had done before them, and as the Turks did afterward. Hence their kinship with European races or manners is really slight, though they have something of Slavic or Russian blood. The Serbians are near akin to the Russians. The Romanians trace their ancestry proudly, if somewhat dubiously, back to the old Roman colonists of the days of Rome’s world empire. The Greeks are really the most ancient dwellers in the region; and to their pride of race was now added a furious eagerness to prove their military power. This had been much scorned after their ineffective war against Turkey in 1897, and they had found no opportunity to give decisive proof of their strength during the war of 1912.

To Professor Duggan’s account of the causes and results of the war, which appeared originally in the Political Science Quarterly, we append the picture of its most striking incidents by Captain Trapmann, who was with the Greek army through its brief but brilliant campaign.

The selections are from:

- The Balkan Question by Stephen P. Duggan.

- With the Conquering Greeks by Capt. A.H. Trapmann.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

There’s 4.5 installments by Stephen P. Duggan and 3.5 installments by Capt. A.H. Trapmann.

We begin with Stephen P. Duggan (1870-1950). He was an American academic who championed internationalism.

Time: 1913

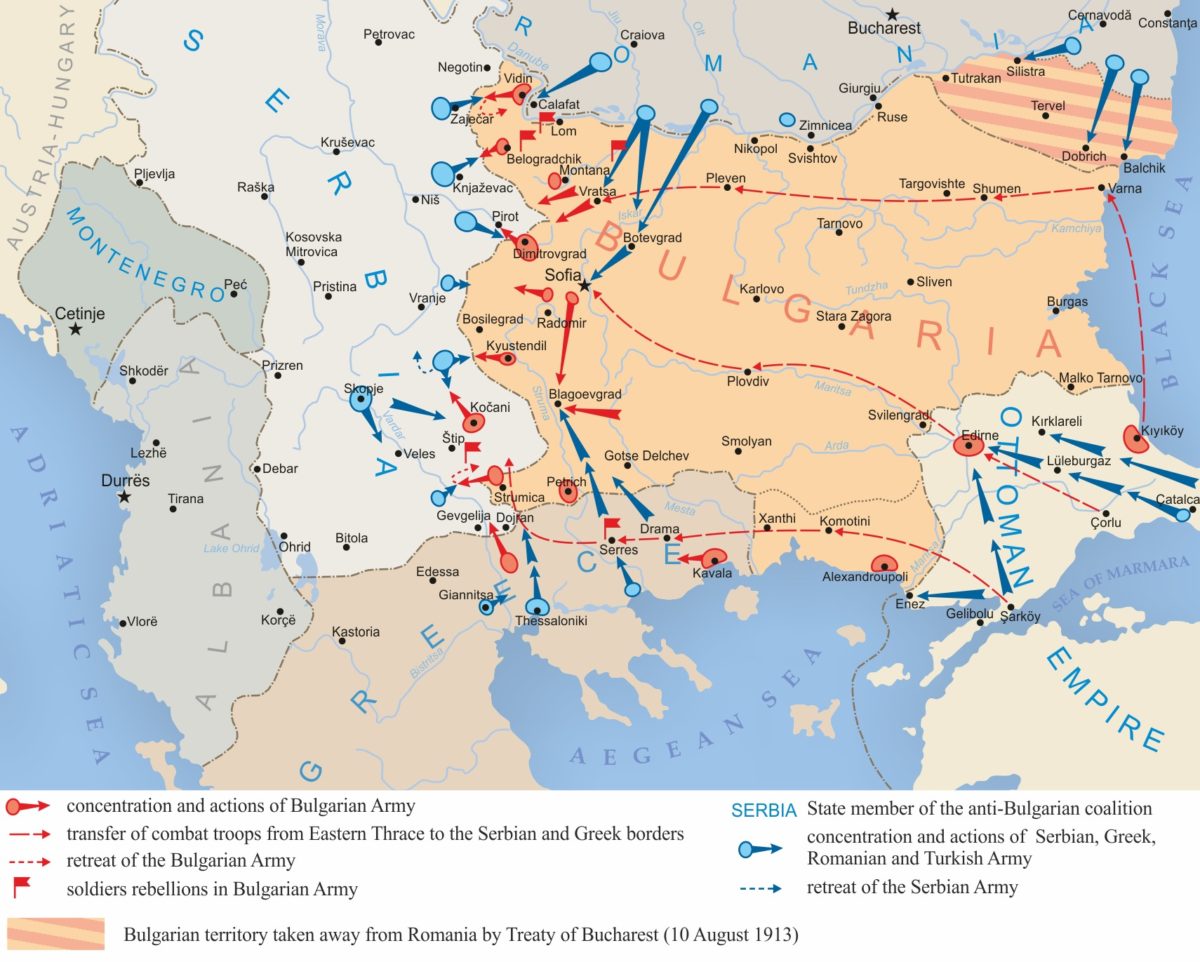

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

When the secret treaty of alliance of March, 1912, between Bulgaria and Serbia against Turkey was signed, a division of the territory that might possibly fall to the allies was agreed upon. Neither Bulgaria nor Serbia has ever published the treaty in full *, but from the denunciations and recriminations indulged in by the parliaments of both, we know in general what the division was to be. The river Maritza, it was hoped, would become the western boundary of Turkey, and a line running from a point just east of Kumanova to the head of Lake Ochrida was to divide the conquered territory between Serbia and Bulgaria. This would give Monastir, Prilip, Ochrida, and Veles to the Bulgarians–a great concession on the part of Serbia. Certain other disputed towns were to be left to the arbitrament of the Czar of Russia. The chief aim to be attained by this division was that Serbia should obtain a seaboard upon the Adriatic Sea, and Bulgaria upon the Aegean. Incidentally Bulgaria would obtain western Thrace and the greater part of Macedonia, and Serbia would secure the greater part of Albania.

[* written in 1914 – ED]

These calculations had been entirely upset by the course of events. Bulgaria’s share had been considerably increased by the unexpected conquest of eastern Thrace, including Adrianople, whereas Serbia’s portion had been greatly diminished by the creation of an independent Albania out of her share. Moreover, M. Pashitch, the Serbian prime minister, maintained that whereas by the preliminary treaty Bulgaria was to send detachments to assist the Serbian armies operating in the Vardar valley, the reverse had been found necessary and Adrianople had only been taken with the help of 60,000 Serbians and by means of the Serbian siege guns. Equity demanded that the new conditions which had arisen and which had entirely altered the situation should be given consideration and that Bulgaria should not expect the preliminary agreement to be carried out. Now, from the outbreak of hostilities Bulgaria’s foreign affairs, in which King Ferdinand was supposed to be supreme, were really controlled by the prime minister, Dr. Daneff. He proved to be the evil genius of his country; for his arrogant, unyielding attitude upon every disputed point, not only with the enemy, but with the allies and with the Powers, destroyed all kindly feeling for Bulgaria, and left her friendless in her hour of need. Dr. Daneff’s answer to the Serbian contention was that Bulgaria bore the brunt of the fight; that, had she not kept the main Turkish force occupied, Serbia and Greece would have been crushed; that a treaty is a treaty, and that the additional gain of eastern Thrace in no way invalidated the old agreement.

The recriminations between Greeks and Bulgarians were quite as bitter. There had been no preliminary agreement as to the division of conquered territory between them, and this permitted each to indulge in the most extravagant claims. The great bone of contention was the possession of the fine port of Salonika. As soon as the war against Turkey broke out, both states pushed forward troops to occupy that city. The Greeks arrived first and were still in possession. Moreover, they maintained that, except for the Jews, the population is chiefly Greek. So are the trade and the schools. M. Venezelos, the Greek prime minister, insisted also that the erection of an independent Albania deprived Greece of a large part of northern Epirus, as it had deprived Serbia of a great part of Old Serbia, and Montenegro of Scutari. In fact, he asserted that Bulgaria alone would retain everything she hoped for, securing nearly three-fifths of the conquered territory, and leaving only two-fifths to be divided among her three allies; and this, despite the fact that but for the activity of the Greek navy in preventing the convoy of Turkey’s best troops from Asia, Bulgaria would never have had her rapid success at the beginning of the war. Finally, he strenuously objected to the whole seaboard of Macedonia going to Bulgaria, as the population where it was not Moslem was chiefly Greek. All the parties to the dispute made much of ethnical and historical claims–“A thousand years are as a day” in their sight. The answer of Dr. Daneff to the Greek demands was to the effect that Greece already had one good port on the Mediterranean, while Bulgaria had none, and that Bulgaria would have to spend immense sums on either Kavala or Dedeagatch to make them of any great value. Moreover, as a result of the war, Greece would get Crete, the Aegean islands, and a good slice of the mainland. She had suffered least in the war and was really being overpaid for her services.

Behind all these formal contentions were the conflicting ambitions and the racial hatreds which no discussion could effectually resolve. Bulgaria was determined to secure the hegemony of the Balkan peninsula. She believed that her role was that of a Balkan Prussia, and her great victories made her confident of her ability to play the role successfully. To this Serbia would never consent. The Serbians far outnumber the Bulgarians. Were they united under one scepter they would be the strongest nation in the Balkans. Their policy is to maintain an equilibrium in the peninsula until the hoped-for annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina will give them the preponderance. This alone would incline Serbia to make common cause with Greece. In addition, she had the powerful motive of direct self-interest. Since she did not secure the coveted territory on the Adriatic, Salonika would be more than ever the natural outlet for her products. Should Bulgaria wedge in behind Greece at Salonika, Serbia would have two Powers to deal with, each of which could pursue the policy of destroying her commerce by a prohibitory tariff, a policy so often adopted toward her by Austria-Hungary. M. Pashitch, therefore, was determined to have the new southern boundary of Serbia coterminous with the northern boundary of Greece. Moreover, Greeks and Serbians were aware of the relative weakness of the Bulgarians due to their great losses and to the wide territory occupied by their troops. The war party was in the ascendant in each country. The Serbians were anxious to avenge Slivnitza, and the Greeks still further to redeem themselves from the reputation of 1897. Had peace been signed in January, there is little doubt that a greater spirit of conciliation would have prevailed. The Young Turks were universally condemned at that time for refusing to yield; but had they deliberately adopted Abdul Hamid’s policy of playing off one people against another, they could not have succeeded better than by their determination to fight.

| Master List | Next—> |

Capt. A.H. Trapmann begins here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.