In the meantime the Powers had not been passive onlookers.

Continuing The Second Balkan War,

with a selection from The Balkan Question by Stephen P. Duggan. This selection is presented in 4.5 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Second Balkan War.

Time: 1913

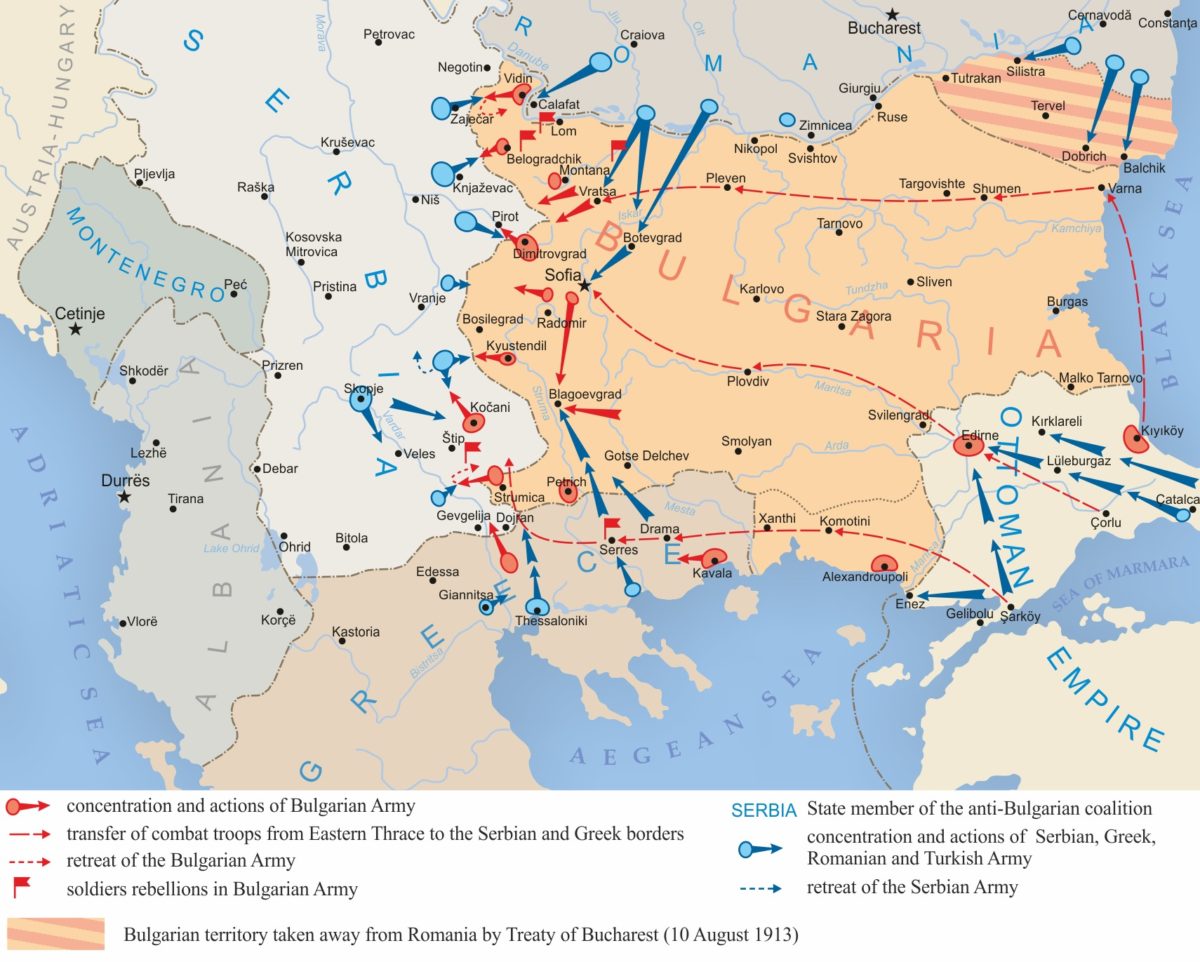

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Each of the belligerent States sent its best man to the peace conference. Greece was represented by M. Venezelos, Serbia by M. Pashitch, Romania by M. Jonescu, Montenegro by M. Melanovitch, and Bulgaria chiefly by General Fitcheff, who had opposed the surprise attack upon the Serbians. The policy of Bulgaria at the conference was to satisfy the demands of Romania at once, sign a separate treaty which would rid her territory of Romanian troops, and then treat with Greece and Serbia. But M. Jonescu, who controlled the situation, insisted that peace must be restored by one treaty, not by several. At the same time he let it be known that Romania would not uphold extravagant claims on the part of Greece and Serbia which they could never have advanced were her troops not at the gates of Sofia. The moderate Romanian demands were easily settled. Her southern boundary was to run from Turtukai via Dobritch to Baltchik on the Black Sea. She also secured cultural privileges for the Kutzovlachs in Bulgaria. The Serbians, who before the second Balkan war would have been satisfied with the Vardar river as a boundary, now insisted upon the possession of the important towns of Kotchana, Ishtib, Radovishta, and Strumnitza, to the east of the Vardar. With the assistance of Romania, Bulgaria was permitted to retain Strumnitza. The Greeks were the most unyielding. Before the war they would have been perfectly satisfied to have secured the Struma river as their eastern boundary. Now they demanded much more of the Aegean seacoast, including the important port of Kavala. The Bulgarian representatives refused to sign without the possession of Kavala, but under pressure from Romania they had to consent. But they would yield on nothing else. The money indemnity demanded by Greece and Serbia and the all-around grant of religious privileges suggested by Romania had to be dropped. The treaty was signed August 6, 1913.

In the meantime the Powers had not been passive onlookers. Austria-Hungary insisted that Balkan affairs are European affairs and that the Treaty of Bucharest should be considered as merely provisional, to be made definitive by the great Powers. On this proposition the members of both the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente divided. Austria and Italy in the one, and Russia in the other, favored a revision. Austria fears a strong Serbia, and Italy dislikes the growth of Greek influence in the eastern Mediterranean. These two States and Russia favored a whittling-down of the gains of Greece and Serbia and insisted upon Kavala and a bigger slice of the Aegean seaboard for Bulgaria. But France, England, and Germany insisted upon letting well-enough alone. King Charles of Romania, who demanded that the peace should be considered definitive, sent a telegram to Emperor William containing the following sentence: “Peace is assured, and thanks to you, will remain definitive.” This gave great umbrage at Vienna; but in the divided condition of the European Concert, no State wanted to act alone. So the treaty stands.

The condition of Bulgaria was indeed pitiable, but her cup was not yet full. Immediately after occupying Adrianople on July 20th, the Turks had made advances to the Bulgarian government looking to the settlement of a new boundary. But Bulgaria, relying upon the intervention of the Powers, had refused to treat at all. On August 7th the representatives of the great Powers at Constantinople called collectively upon the Porte to demand that it respect the Treaty of London. But the Porte had seen Europe so frequently flouted by the little Balkan States during the previous year, that it had slight respect for Europe as a collective entity. In fact, Europe’s prestige at Constantinople had disappeared. J’y suis, j’y reste was the answer of the Turks to the demand to evacuate Adrianople. The recapture of that city had been a godsend to the Young Turk party. The Treaty of London had destroyed what little influence it had retained after the defeat of the armies, and it grasped at the seizure of Adrianople as a means of awakening enthusiasm and keeping office. As the days passed by, it became evident that further delay would cost Bulgaria dear. On August 15th the Turkish troops crossed the Maritza river and occupied western Thrace, though the Porte had hitherto been willing to accept the Maritza as the boundary. The Bulgarian hope of a European intervention began to fade. The Turks were soon able to convince the Bulgarian Government that most of the great Powers were willing to acquiesce in the retention of Adrianople by the Turks in return for economic and political concessions to themselves. There was nothing for Bulgaria to do but yield, and on September 3d General Savoff and M. Tontcheff started for Constantinople to treat with the Turkish government for a new boundary line. They pleaded for the Maritza as the boundary between the two States, the possession of the west bank being essential for railway connection between Bulgaria and Dedeagatch, her only port on the Aegean. But this plea came in conflict with the determination of the Turks to keep a sufficient strategic area around Adrianople. Hence the Turks demanded and secured a considerable district on the west bank, including the important town of Dimotika. By the preliminary agreement signed on September 18th the boundary starts at the mouth of the Maritza river, goes up the river to Mandra, then west around Dimotika almost to Mustafa Pasha. On the north the line starts at Sveti Stefan and runs west so that Kirk Kilesseh is retained by Turkey.

While the Balkan belligerents were settling upon terms of peace among themselves, the conference of ambassadors at London was trying to bring the settlement of the Albanian problem to a conclusion. On August 11th the conference agreed that an international commission of control, consisting of a representative of each of the great Powers, should administer the affairs of Albania until the Powers should select a prince as ruler of the autonomous State. The conference also decided to establish a gendarmerie under the command of military officers selected from one of the small neutral States of Europe. At the same time the conference agreed upon the southern boundary of Albania. This line was a compromise between that demanded by Greece and that demanded by Austria-Hungary and Italy. Unfortunately it was agreed that the international boundary commission which was to be appointed should in drawing the line be guided mainly by the nationality of the inhabitants of the districts through which it would pass. At once Greeks and Albanians began a campaign of nationalization in the disputed territory, which resulted in sanguinary conflicts.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Stephen P. Duggan begins here. Capt. A.H. Trapmann begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.