The chief factor that made for victory–the unspeakable horror, loathing, and rage aroused by the atrocities committed upon the Greek wounded whenever a temporary local reverse left a few of the gallant fellows at the mercy of the Bulgarians.

Continuing The Second Balkan War,

our selection from With the Conquering Greeks by Capt. A.H. Trapmann. The selection is presented in 3.5 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Second Balkan War.

Time: 1913

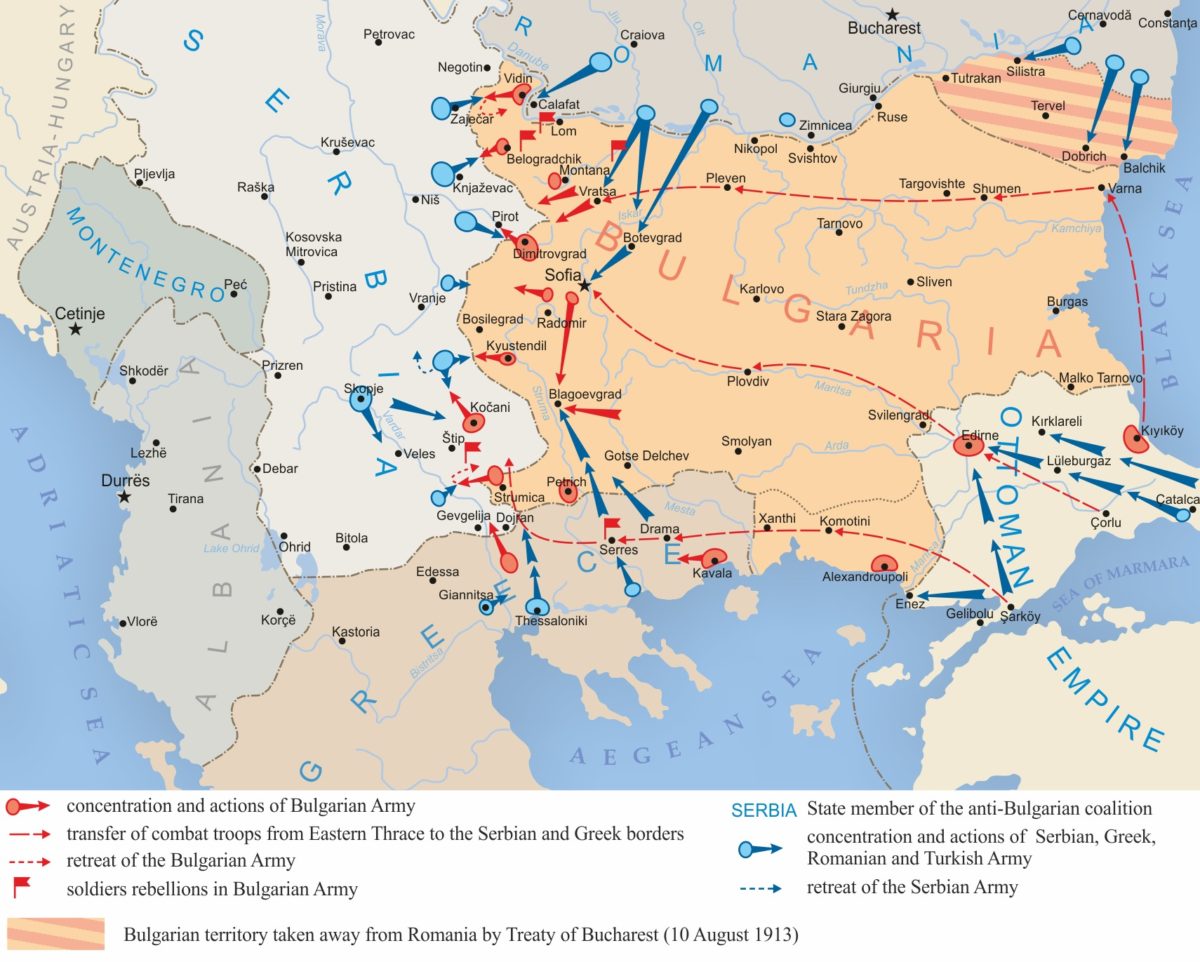

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

On the 3rd and 4th the Bulgarians retired sullenly northward toward Doiran, contesting every yard and putting in the units of the 14th Division as quickly as they could be detrained; but the Greeks never flagged for one moment in the pursuit. The 10th and 3d Divisions, marching at tremendous speed, came up on the left, menacing the line of retreat on Strumnitza. It was in the pass ten miles south of this town that remnants of the Bulgarian 3d and 14th Divisions made their last stand upon the 8th of July. Throughout the week they had been fighting and retreating incessantly, had lost at least 10,000 in killed and wounded, some 4,500 prisoners, and about forty guns, while the Greeks lost about 4,500 and 5,000 men in front of Kilkis and another 3,000 between Doiran and Strumnitza.

Meanwhile at Lakhanas an equally sanguinary two days’ conflict had been in progress. The Greeks attacked and finally captured the Bulgarian entrenched positions. Time after time their charges failed to reach, but eventually their persistent courage and inimitable élan won home, and the Bulgarians fled in utter rout and panic, leaving everything, even many of their uniforms, behind them.

King Constantine, speaking in Germany recently, attributed the success of the Greek armies to the courage of his men, the excellence of the artillery, and to the soundness of the strategy, but I think he overlooked the chief factor that made for victory–the unspeakable horror, loathing, and rage aroused by the atrocities committed upon the Greek wounded whenever a temporary local reverse left a few of the gallant fellows at the mercy of the Bulgarians. I have seen an officer and a dozen men who had had their eyes put out, and their ears, tongues, and noses cut off, upon the field of battle during the lull between two Greek charges. And there were other worse, but nameless, barbarities both upon the wounded and the dead who for a brief moment fell into Bulgarian hands.

This was during the very first days of the war; later, when the news of the wholesale massacres of Greek peaceable inhabitants at Nigrita, Serres, Drama, Doxat, etc., became known to the army, it raised a spirit which no pen can describe. The men “saw red,” they were drunk with lust for honorable revenge, from which nothing but death could stop them. Wounds, mortal wounds, were unheeded so long as the man still had strength to stagger on; I have seen a sergeant with a great fragment of common shell through his lungs run forward for several hundred yards vomiting blood, but still encouraging his men, who, truth to tell, were as eager as he. It is impossible to describe or even conceive the purposeful and aching desire to get to close quarters regardless of all losses and of all consequences. The Bulgarians, in committing those obscene atrocities, not only damned themselves forever in the eyes of humanity, but they doubled, nay, quadrupled, the strength of the Greek army. Nothing short of extermination could have prevented the Greek army from victory; there was not a man who would not have a million times rather died than have hesitated for a moment to go forward.

The days of those first battles were steaming hot with a pitiless Macedonian sun. The Greek troops were in far too high a state of spiritual excitation to require food, even if food had been able to keep pace with their lightning advance. All that the men wanted, all they ever asked for, was water and ammunition; and here the greatest self-sacrifice of all to the cause was frequently seen; for a wounded man, unable to struggle forward another yard, would, as he fell to the ground, hastily unbuckle water-bottle and cartridge-cases and hand them to an advancing comrade with a cheery word, “Go on and good luck, my lad,” and then as often as not he would lay him down to die with parched lips and cleaving tongue.

I was myself, at the pressing and personal invitation of King Constantine, the first to visit Nigrita, where the Bulgarian General, before leaving, had the inhabitants locked into their houses, and then with guncotton and petroleum burned the place to the ground. Here 470 victims were burned alive, mostly old folk, women, and children. Serres, Drama, Kilkis, and Demir Hissar (all important towns) have similar tales to tell, only the death-roll is longer. Small wonder that these stories of ferocity are not given credence, for they are incredible, and it is only when one studies the Bulgarian character that one can understand how such orgies of carnage were possible.

The scope of this article does not permit me to describe in detail the minor battles and operations between the 6th of July and the 25th of July; suffice it to say that the rapidity of the Greek advance upon Strumnitza and up the valley of the Struma forced the Bulgarians to beat in full retreat toward their frontier, leaving behind them all that impeded their flight. Military stores, guns, carts, and even uniforms strewed the line of their march, and they were only saved from annihilation because the mountains which guarded their flanks were impassable for the Greek artillery. By blowing up the bridges over the Struma the impetuosity of the Greek pursuit was delayed, and it was in the Kresna Pass that the Bulgarian rear-guard first turned at bay. The pass is a twenty-mile gorge cut through mountains 7,000 feet high, but the Greeks turned the Bulgarian positions by marching across the mountains, and it was near Semitli, five miles north of the pass, that the Bulgarians offered their last serious resistance. It was a wonderful battle. The Greeks, at the urgent request of the Serbian General Staff, had detailed two divisions to help the Serbians. On the west bank of the Struma they pushed the 2d and 4th Divisions gently northward, while in the narrow Struma valley (it is little better than a gorge in most places) they had the 1st Division on the main road with the 5th behind it in reserve; on the right, perched on the summit of well-nigh inaccessible mountains, was the Greek 6th Division, with the 7th Division on its right, somewhat drawn back.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Stephen P. Duggan began here. Capt. A.H. Trapmann began here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.