Never in the history of the human race have such enormities been committed upon the helpless civilian inhabitants of a war-stricken land.

Continuing The Second Balkan War.

Today is our final installment from Stephen P. Duggan and then we begin the second part of the series with Capt. A.H. Trapmann. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Second Balkan War.

Time: 1913

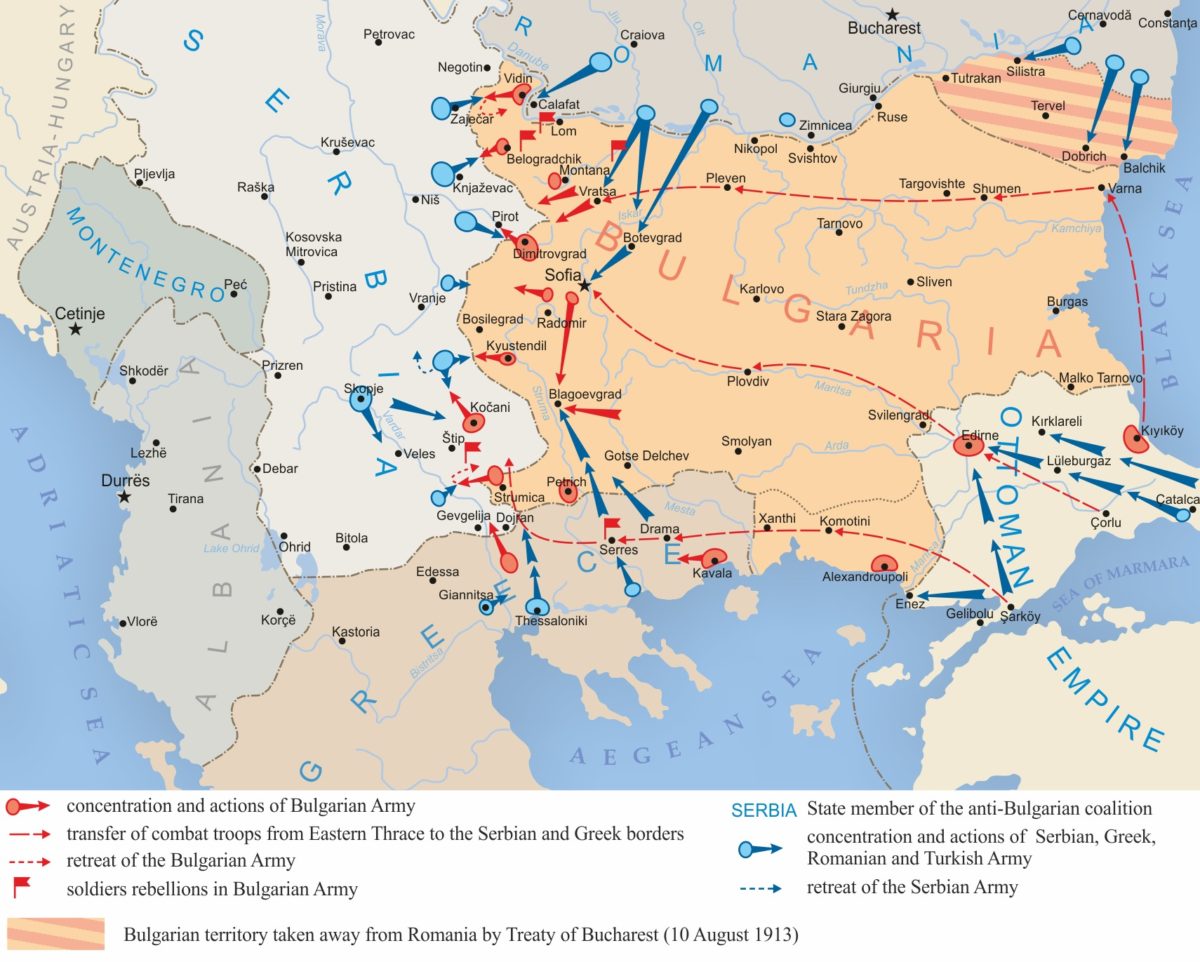

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Unrest soon spread throughout the whole of Albania. On August 17th a committee of Malissori chiefs visited Admiral Burney, who was in command, at Scutari, of the marines from the international fleet, to notify him that the Malissori would never agree to incorporation in Montenegro. They proceeded to make good their threat by capturing the important town of Dibra and driving the Serbians from the neighborhood of Djakova and Prizrend. Since then the greater part of northern and southern Albania has been practically in a state of anarchy.

The settlement of the Balkans described in this article will probably last for at least a generation, not because all the parties to the settlement are content, but because it will take at least a generation for the dissatisfied States to recuperate. Bulgaria is in far worse condition than she was before the war with Turkey. The second Balkan war, caused by her policy of greed and arrogance, destroyed 100,000 of the flower of her manhood, lost her all of Macedonia and eastern Thrace, and increased her expenses enormously. Her total gains, whether from Turkey or from her former allies, were but eighty miles of seaboard on the Aegean, with a Thracian hinterland wofully depopulated. Even railway communication with her one new port of Dedeagatch has been denied her. Bulgaria is in despair, but full of hate. However, with a reduced population and a bankrupt treasury, she will need many years to recuperate before she can hope to upset the new arrangement. And it will be hard even to attempt that; for the status quo is founded upon the principle of a balance of power in the Balkan peninsula; and Romania has definitely announced herself as a Balkan power. Serbia, and more particularly Greece, have made acquisitions beyond their wildest dreams at the beginning of the war and have now become strong adherents of the policy of equilibrium.

The future of the Turks is in Asia, and Turkey in Asia just now is in a most unhappy condition. Syria, Armenia, and Arabia are demanding autonomy; and the former respect of the other Moslems for the governing race, i.e., the Turks, has received a severe blow. Whether Turkey can pull itself together, consolidate its resources, and develop the immense possibilities of its Asiatic possessions remains, of course, to be seen. But it will have no power, and probably no desire, to upset the new arrangement in the Balkans.

The settlement is probably a landmark in Balkan history in that it brings to a close the period of tutelage exercised by the great Powers over the Christian States of the Balkans. Neither Austria-Hungary nor Russia emerges from the ordeal with prestige. The pan-Slavic idea has received a distinct rebuff. To Romania and Greece, another non-Slavic State, i.e., Albania, has been added; and in no part of the peninsula is Russia so detested as in Bulgaria which unreasonably protests that Russia betrayed her. “Call us Huns, Turks, or Tatars, but not Slavs.” Twice the Austro-Hungarians, in their anxiety to maintain the balance of power in the Balkans, made the mistake of backing the wrong combatant. In the first war, they upheld Turkey; and in the second, they favored Bulgaria. In encouraging Bulgarian aggression they estranged Romania, the faithful friend of a generation, and Bulgaria won only debt and disgrace. Yet Austria-Hungary must now continue to support Bulgaria as a counterpoise to a stronger Serbia which they consider a menace to their security because of Serbian influence on their southern Slavs. The Balkan states will manage their own affairs in the future, but they will still offer abundant opportunity for the play of Russian and Austro-Hungarian rivalry. It had been hoped that the Balkan peninsula, when freed from the incubus of Turkish misrule, would settle down to a period of general tranquillity. Instead of this, the ejectment of the Turk has resulted in increased bitterness and more dangerous hate.

Now we begin the second the second part of our series with our selection from With the Conquering Greeks by Capt. A.H. Trapmann. The selection is presented in 3.5 easy 5 minute installments.

I doubt if history can show a more brilliant or dramatic campaign than that which the Greeks commenced on the first of July and ended on the last day of the same month; certainly no country has ever been drenched with so much blood in so short a space of time as was Macedonia, and never in the history of the human race have such enormities been committed upon the helpless civilian inhabitants of a war-stricken land.

Bulgaria felt herself amply strong enough to crush the Serbian and Greek armies single-handed, provided peace with Turkey could be assured, and the Bulgarian troops at Tchataldja set free. Thus, while Bulgaria talked loudly about the conference at St. Petersburg, she was making feverish haste to persuade the Allies to join with her in concluding peace with Turkey. But the Allies were quite alive to the dangers they ran. As peace with Turkey became daily more assured, the Bulgarian army at Tchataldja was gradually withdrawn and transported to face the Greek and Serbian armies in Macedonia.

But meanwhile Bulgaria had got one more preparation to make. Her plan was to attack the Allies suddenly, but to do it in such a way that the Czar and Europe might believe that the attack was mutual and unpremeditated. She therefore set herself to accustom the world to frontier incidents between the rival armies. On no fewer than four occasions various Bulgarian generals acting under secret instructions attacked the Greek or Serbian troops in their vicinity. The last of these incidents, which was by far the most serious, took place on the 24th of May in the Pangheion region, when the sudden attack at sunset of 25,000 Bulgarians drove the Greek defenders back some six miles upon their supports. On each occasion the Bulgarian Government disclaimed all responsibility, and attributed the bloodshed to the personal initiative of individual soldiers acting under (imaginary) provocation.

The incident of the 24th of May cost the Bulgarians some 1,500 casualties, while the Greeks lost about 800 men, sixteen of whom were prisoners; two of these subsequently died from ill-treatment. In connection with this last “incident” a circumstance arose which demonstrates more vividly than mere adjectives the underhand methods employed by the Sofia authorities. It was announced that the Bulgarians had captured six Greek guns, and these were duly displayed at Sofia and inspected by King Ferdinand. I myself was at Salonica at the time, and, knowing that this was not true, I protested through the Daily Telegraph against the misleading rumor. A controversy arose, but it was subsequently proved by two artillery experts who inspected the guns in question that they were really Bulgarian guns painted gray, with their telltale breech-blocks removed.

On the morning of the 29th of June we at Salonica received the news that during the night Bulgarian troops in force had attacked the Greek outposts in the Pangheion region and driven them in. All through the day came in fresh news of further attacks all along the line. At Guevgheli, where the Greek and Serbian armies met, the Bulgarians had attacked fiercely, occupied the town, and cut the railway line. The two armies were separated from each other by an interposing Bulgarian force. On the morning of the 30th of June it was learned that all along the line the Bulgarians had crossed the neutral line and were advancing, while at Nigrita they had driven back a Greek detachment and pressed some fifteen miles southward, thus threatening entirely to cut off the Greek troops remaining in the Pangheion district. The situation was critical and demanded prompt attention. King Constantine was away at Athens, but he sent his instructions by wireless and hastened hotfoot back to Salonica to place himself at the head of the army.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Stephen P. Duggan began here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.