This series has seven easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: The Federal Government Takes Up Protectionism.

Introduction

President Jackson had almost reached the end of his first term when a crisis second in gravity only to that of the Civil War threatened the peace and integrity of the American Union. The passage of the Ordinance of Nullification by a State convention of South Carolina. in November. 1832. accompanied with the threat of secession. filled the whole country with apprehension and alarm. By his energetic measures in dealing with this critical state of affairs. Jackson confirmed his reputation for courage and decision. and. what was far more important. averted for the time the danger of civil conflict between the States.

The doctrine of nullification. or the constitutional right of a State of the American Union to refuse obedience to an act of Congress. was introduced as early as 1798. when the Virginia Resolutions, prepared by James Madison, declared that the Alien and Sedition acts were “palpable and alarming infractions of the Constitution” and that when the Federal Government assumed powers not delegated by the States “a nullification of the act was the rightful remedy.” It was but the extended reaffirmation of this doctrine when in 1832 South Carolina. objecting to the collection of duties in Charleston harbor, made the declaration. “that any State had a right to nullify such of the laws of the United States as might not be acceptable to her.”

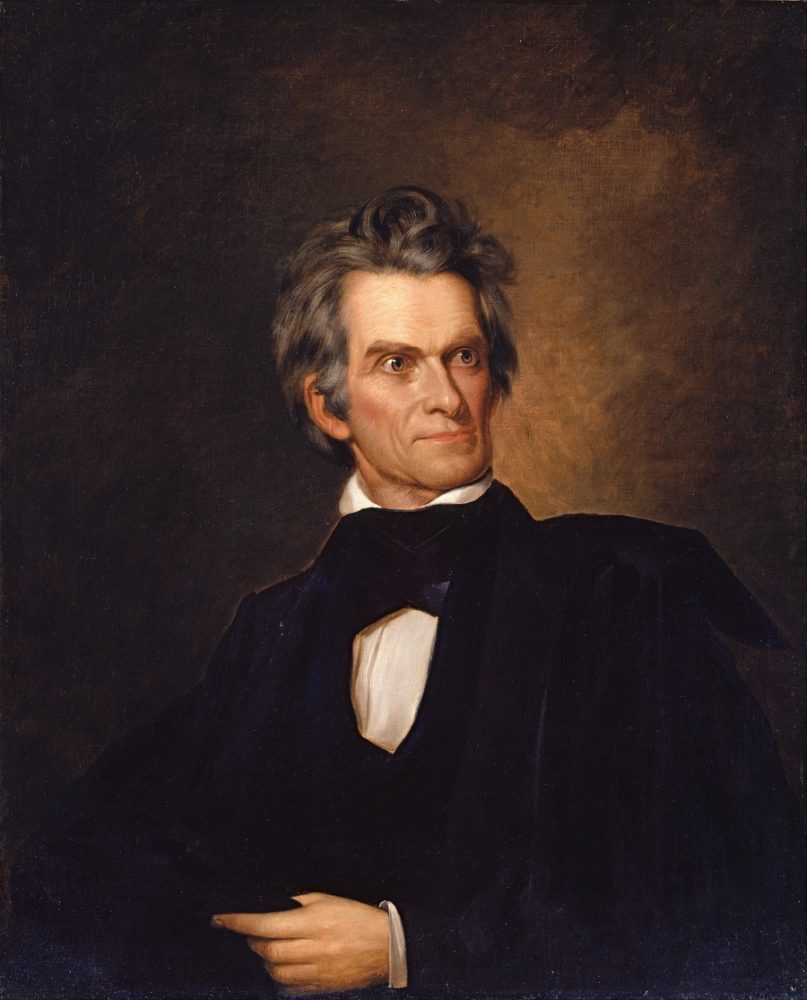

The nullifiers of 1798 protested against what they regarded as Federal usurpation. Those of 1832 were divided in their interpretation of the Virginia Resolutions, extremists holding that they implied the right of any State to secede at will. It is commonly held today that this was the real meaning of the nullifiers of 1832. The soul of the South Carolina nullification was John C. Calhoun. “Calhoun began it; Calhoun continued it; Calhoun stopped it.” says one historian. But such political acts have causes that are more than personal. The South Carolina Ordinance of Nullification grew out of questions connected with the tariff. which had long been a source of disagreement and perplexity among the American people. The War of 1812 had been expensive and in order to pay the interest on the debt and reduce the principal the Government had greatly to increase its revenues. The growing manufacturing interests of the North asked and received protection. The early protectionists were led by Calhoun and Clay. Calhoun being especially zealous. From this period the tariff became one of the most difficult and persistent subjects of American statesmanship. Calhoun’s attitude underwent a complete change and matters reached a climax in South Carolina.

Parton, who, in a wide range of authorship, devoted particular attention to this passage in American history. gives us a comprehensive and lucid presentation of the whole subject. with the historical background essential to its full understanding. His citations from Calhoun add the authority of his perspective to the following narrative.

This selection is from Life of Andrew Jackson by James Parton published in 1860. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

James Parton (1822-1891) was the most popular American biographer of his day.

Time: 1832

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The protectionists triumphed in 1816. In the tariff bill of 1820 the principle was carried further and still further in those of 1824 and 1828. Under the protective system manufactures flourished and the public debt was greatly diminished. It attracted skillful workmen to the country. as John C. Calhoun had said it would. and contributed to swell the tide of ordinary emigration.

But about the year 1824 it began to be thought that the advantages of the system were enjoyed chiefly by the Northern States. and the South hastened to the conclusion that the protective system was the cause of its lagging behind. There was. accordingly. a considerable Southern opposition to the tariff of 1824. and a general Southern opposition to that of 1828. In the latter year, however, the South elected to the Presidency General Jackson, whose votes and whose writings had committed him to the principle of protection. Southern politicians felt that the General, as a Southern man, was more likely to further their views than Messrs. Adams and Clay, both of whom were peculiarly devoted to protection.

As the first years of General Jackson’s Administration wore away without affording to the South the “relief” which they had hoped from it, the discontent of the Southern people increased. Circumstances gave them a new and most telling argument. In 1831 the public debt had been so far diminished as to render it certain that in three years the last dollar of it would be paid. The Government had been collecting about twice as much revenue as its annual expenditures required. In three years, therefore, there would be an annual surplus of twelve or thirteen millions of dollars. The South demanded, with almost a united voice, that the duties should be reduced so as to make the revenue equal to the expenditure and that. in making this reduction. the principle of protection should be, in effect, abandoned, Protection should thenceforth be “incidental” merely, the country. The President’s message announced that, in view of the speedy extinction of the public debt, it was high time that Congress should prepare for the threatened surplus.

Clay, after an absence from the halls of Congress of six years, returned to the Senate in December, 1831 — an illustrious figure, the leader of the opposition, its candidate for the Presidency, his old renown enhanced by his long exile from the scene of his well remembered triumphs. The galleries filled when he was expected to speak. He was in the prime of his prime. He never spoke so well as then, nor as often, nor so long, nor with so much applause. But he either could not or dared not undertake the choking of the surplus. He proposed merely “that the duties upon articles imported from foreign countries, and not coming into competition with similar articles made or produced within the United States, be forthwith abolished, except the duties upon wines and silks, and that those be reduced.” After a debate of months’ duration, a bill in accordance with this proposition passed both Houses and was signed by the President. It preserved the protective principle intact; it reduced the income of the Government about three million dollars; and it inflamed the discontent of the South to such a degree, that one State. under the influence of a man of force became capable of —- nullification.

The President signed the bill, as he told his friends, because he deemed it an approach to the measure required. His influence during the session had been secretly exerted in favor of compromise. Major Lewis, at the request of the President, had been much in the lobbies and committee-rooms of the Capitol, urging members of both sections to make concessions. The President thought that the just course lay between the two extremes of abandoning the protective principle and reducing the duties in total disregard of it.

“You must yield something on the tariff question,” said Major Lewis to the late Governor Marcy, of New York. “or Van Buren will be sacrificed.” Said Governor Marcy in reply: “I am Van Buren’s friend, but the protective system is more important to New York than Van Buren.”

To return to Calhoun. He had been elected Vice-President, but soon disagreed with Jackson’s measures. His hostile correspondence with the President was published by him in the spring of 1831. The President retorted by getting rid of the three members of the Cabinet who favored the succession of Calhoun to the Presidency. Three months afterward, in the Pendleton Messenger of South Carolina. Calhoun continued the strife by publishing his first treatise upon nullification. As there was no obvious reason for such a publication at that moment the Vice-President began his essay by giving a reason for it.

“It is one of the peculiarities,” said he,

of the station I occupy that while it necessarily connects its incumbent with the politics of the day, it affords him no opportunity officially to express his sentiments, except accidentally on an equal division of the body over which he presides. He is thus exposed, as I have often experienced, to have his opinions erroneously and variously represented. In ordinary cases the correct course I conceive to be to remain silent, leaving to time and circumstances the correction of misrepresentations; but there are occasions so vitally important that a regard both to duty and character would seem to forbid such a course; and such I conceive to be the present. The frequent allusions to my sentiments will not permit me to doubt that such also is the public conception, and that it claims the right to know, in relation to the question referred to, the opinions of those who hold important official stations; while on my part desiring to receive neither unmerited praise nor blame, I feel, I trust, the solicitude which every honest and independent man ought, that my sentiments should be truly known, whether they be such as may be calculated to recommend them to public favor or not. Entertaining these impressions, I have concluded that it is my duty to make known my sentiments; and I have adopted the mode which, on reflection, seemed to be the most simple and best calculated to effect the object in view. “

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.