This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: The Cloud From Vesuvius.

Introduction

Among the historic calamities of the world none has gathered about itself more of human interest, whether in connection with the study of ancient cities and customs or in the calling forth of sympathy through the magical treatment of imaginative literature, than the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, which occurred at the beginning of the reign of Titus. The eruption was accompanied by an earthquake, and the combination of natural commotions caused the complete ruin and burial of the two cities.

One of the most vivid descriptions of the catastrophe is that given in the account of Dion Cassius. Among those who perished in the disaster was the elder Pliny, the celebrated naturalist; and the most famous narrative of the eruption is that here given of Pliny the Younger, nephew of the other, in the two letters which he wrote to Tacitus in order to supply that historian with accurate details.

Lytton’s well-known _Last Days of Pompeii_, although a work of imagination, deals with this subject in a manner which almost simulates the realistic tale of an actual observer; and his account, linking the calamity itself with the revelations of the earlier explorers of the buried city, after so many centuries had passed, well deserves a place in connection with the story of the older and more circumstantial writer.

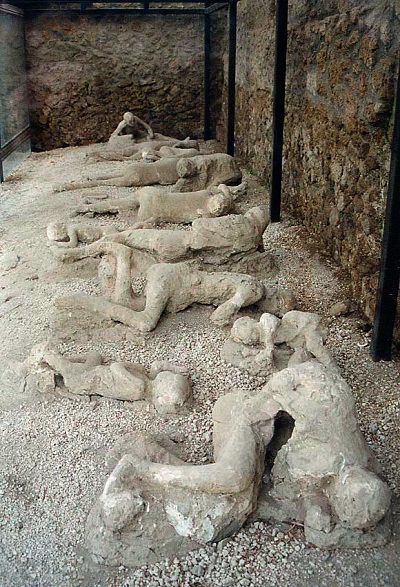

One of the earliest important discoveries at Pompeii, made in 1771, was that of the “Villa of Diomedes,” named from the tomb of Marcus Arrius Diomedes across the street. Since then every decade has seen some progress in the work of excavation, and among other buildings brought to light are the “House of Pansa,” the “House of the Tragic Poet,” the “House of Sallustius,” the “Castor and Pollux,” a double house, and the “House of the Vettii” — the last, a recent discovery, being left with all its furnishings as found. Many interesting objects have been discovered lately, and a complete picture can now be presented of a small Italian city and its life in the first century A.D. Valuable finds are wall paintings, illustrative of decorative art; floor mosaics, etc., which may be seen in the Royal Museum of Naples. Another of the most recent discoveries is that of the temple of Venus Pompeiana in the southern corner of the city; others are the remains of persons who, carrying valuables, perished in a wayside inn where they had sought refuge. At the present time about one-half of the city has been excavated, and the circuit of the walls has been found to be about two miles. The uncovering of the whole city will probably require many years. Excavations now being made in the adjacent country promise results as interesting as those already obtained within the city limits.

The selections are from:

- Letters to Tacitus by Pliny the Younger published in around 105.

- The Last Days of Pompeii by Edward Bulwer-Lytton published in 1834.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

There’s 3 installments by Pliny and 2 installments by Edward Bulwer-Lytton.

We begin with Pliny (61 AD-113). He was an imperial magistrate in the Roman Empire. He maintained a vast correspondence with many of the leaders of his time.

Time: October or November 79 AD

Place: Pompeii, Italy

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Your request that I would send you [Tacitus] an account of my uncle’s death, in order to transmit a more exact relation of it to posterity, deserves my acknowledgments; for, if this accident shall be celebrated by your pen, the glory of it, I am well assured, will be rendered forever illustrious. And notwithstanding he perished by a misfortune, which as it involved at the same time a most beautiful country in ruins, and destroyed so many populous cities, seems to promise him an everlasting remembrance; notwithstanding he has himself composed many and lasting works; yet I am persuaded, the mentioning of him in your immortal writings will greatly contribute to render his name immortal.

Happy I esteem those to be to whom by provision of the gods has been granted the ability either to do such actions as are worthy of being related or to relate them in a manner worthy of being read; but peculiarly happy are they who are blessed with both these uncommon talents: in the number of which my uncle, as his own writings and your history will evidently prove, may justly be ranked. It is with extreme willingness, therefore, that I execute your commands; and should indeed have claimed the task if you had not enjoined it. He was at that time with the fleet under his command at Misenum.

On the 24th of August, about one in the afternoon, my mother desired him to observe a cloud which appeared of a very unusual size and shape. He had just taken a turn in the sun, [1] and, after bathing himself in cold water, and making a light luncheon, gone back to his books: he immediately arose and went out upon a rising ground from whence he might get a better sight of this very uncommon appearance. A cloud, from which mountain was uncertain at this distance (but it was found afterward to come from Mount Vesuvius [2]) was ascending, the appearance of which I cannot give you a more exact description of than by likening it to that of a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of branches; occasioned, I imagine, either by a sudden gust of air that impelled it, the force of which decreased as it advanced upward, or the cloud itself, being pressed back again by its own weight, expanded in the manner I have mentioned; it appeared sometimes bright and sometimes dark and spotted, according as it was either more or less impregnated with earth and cinders.

[1: The Romans used to lie or walk naked in the sun, after anointing their bodies with oil, which was esteemed as greatly contributing to health, and therefore daily practiced by them. This custom, however, of anointing themselves, is inveighed against by the satirists as in the number of their luxurious indulgences; but since we find the elder Pliny here, and the amiable Spurinna in a former letter, practicing this method, we cannot suppose the thing itself was esteemed unmanly, but only when it was attended with some particular circumstances of an over-refined delicacy. – ED]

[2: About six miles distant from Naples. – ED]

This phenomenon seemed to a man of such learning and research as my uncle extraordinary and worth further looking into. He ordered a light vessel to be got ready, and gave me leave, if I liked, to accompany him. I said I had rather go on with my work; and it so happened he had himself given me something to write out. As he was coming out of the house, he received a note from Rectina, the wife of Bassus, who was in the utmost alarm at the imminent danger which threatened her; for her villa lying at the foot of Mount Vesuvius, there was no way of escape but by sea; she earnestly entreated him therefore to come to her assistance.

He accordingly changed his first intention, and what he had begun from a philosophical, he now carried out in a noble and generous, spirit. He ordered the galleys to put to sea, and went himself on board with an intention of assisting not only Rectina, but the several other towns which lay thickly strewn along that beautiful coast. Hastening then to the place from whence others fled with the utmost terror, he steered his course direct to the point of danger, and with so much calmness and presence of mind as to be able to make and dictate his observations upon the motion and all the phenomena of that dreadful scene. He was now so close to the mountain that the cinders, which grew thicker and hotter the nearer he approached, fell into the ships, together with pumice-stones and black pieces of burning rock: they were in danger too not only of being aground by the sudden retreat of the sea, but also from the vast fragments which rolled down from the mountain and obstructed all the shore. Here he stopped to consider whether he should turn back again; to which the pilot advising him, “Fortune,” said he, “favors the brave; steer to where Pomponianus is.” Pomponianus was then at Stabiae, separated by a bay, which the sea, after several insensible windings, forms with the shore. He had already sent his baggage on board; for though he was not at that time in actual danger, yet being within sight of it, and indeed extremely near, if it should in the least increase, he was determined to put to sea as soon as the wind, which was blowing dead in-shore, should go down. It was favorable, however, for carrying my uncle to Pomponianus, whom he found in the greatest consternation: he embraced him tenderly, encouraging and urging him to keep up his spirits, and, the more effectually to soothe his fears by seeming unconcerned himself, ordered a bath to be got ready, and then, after having bathed, sat down to supper with great cheerfulness, or at least — what is just as heroic — with every appearance of it.

| Master List | Next—> |

Edward Bulwer-Lytton begins here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.