Today’s installment concludes How to Handle Arabs,

our selection from With Lawrence in Arabia by Lowell Thomas published in 1924.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in How to Handle Arabs.

Time: World War I

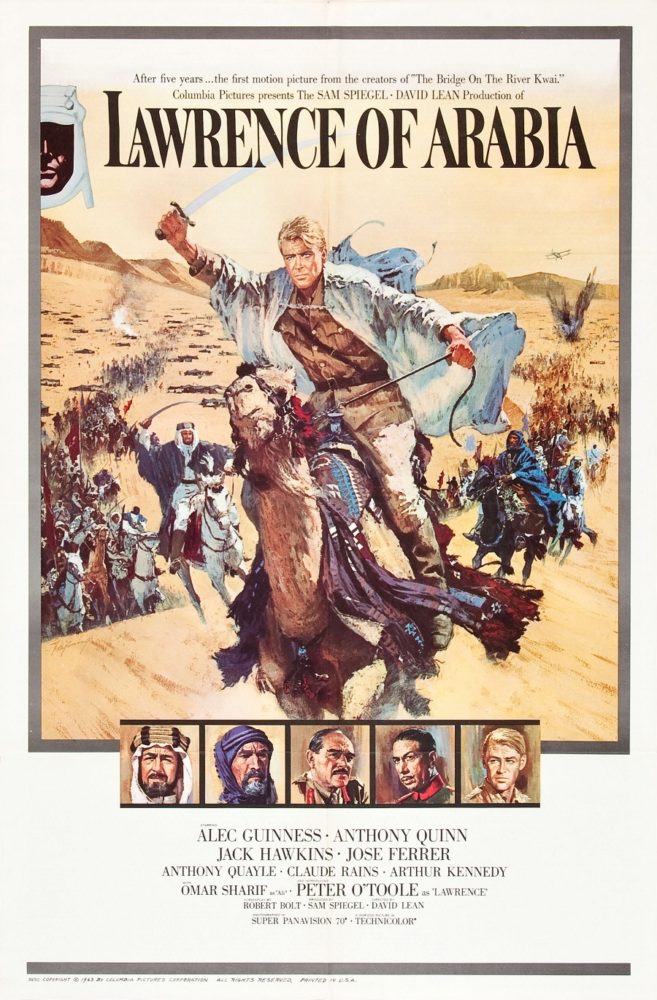

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Until he became an undisputed leader, Lawrence kept in constant touch with the king of the Hedjaz and his four sons, principally Emir Feisal. He lived with the leaders that he might be with them when they were dining or holding audiences in their tents. It was his theory that giving direct and formal advice was not nearly so effective as the constant dropping of ideas in casual talk. At his meals the Arab is off guard and at his ease, engaging in small talk and general conversation. Whenever Lawrence wanted to make a new move, start a raid, or capture a town, he would bring up the question casually and indirectly, and before half an hour had passed he usually succeeded in inspiring one of the prominent sheiks to suggest the plan. Lawrence would then seize his advantage, and before the sheik’s enthusiasm had time to wane he would push him on to the execution of the plan.

On one occasion Lawrence was dining with Emir Feisal and some of his leaders, not far from Akaba. The Arab chieftains thought it would be a splendid plan to take Deraa, the important railway junction hundreds of miles farther north, just south of Damascus. Lawrence knew that Deraa could be captured, but he also realized that at that stage of the campaign it could not be held for any length of time; so he said: “Oh, yes, that’s a fine idea! But first, let’s work out the details.” A great council of war was held, but somehow the longer the matter was discussed the less enthusiasm manifested itself. In fact, the Arab leaders became so disheartened that they even suggested retreating from the position that they occupied at that moment. Then Lawrence delicately suggested that such a retreat would greatly anger King Hussein, and little by little he prevailed upon them to go through with the original plan for capturing Akaba, which was his first objective.

As Lawrence once remarked to me under his breath when we were attending a consultation of Arab leaders: “Everybody is a general in the Arab army. In British circles a general is allowed to make a mess of things by himself, whereas here in Arabia every man wants a hand in making the mess complete.”

The Arab Shereefs and sheiks are strong-minded and obstinate men. Nothing hurts them more than to have some one point out their mistakes. If you say “rubbish” to an Arab, it is sure to put his back up, and he will ever afterward decline to help you. Lawrence never refused to consider any scheme that was put forward, even though he had the actual power to do so. Instead, he always approved a plan and then skilfully directed the conversation so that the Arab himself modified it to suit Lawrence, who would then announce it publicly to the other Arab leaders before the originator of the scheme had time to change his point of view. All this would be manipulated in such a delicate way that the Arab would not for a moment be aware that he was acting under pressure. If Lawrence and his British associates had acted behind the shereef’s back they might have attained certain of their objectives in half the time, but until Lawrence actually had been raised to supreme command by the voluntary act of the Arabs themselves and was regarded by them as a sort of superman he was wise enough never to give direct orders. Even his suggestions and advice to Emir Feisal he reserved until they were alone. From the beginning of the campaign Lawrence adopted the policy of trying not to do too much himself, always remembering that it was the Arab’s war. At times, when it seemed necessary, he would even strengthen the prestige of the Arab leaders with their subordinates at the expense of his own position. The failure of the Turks and Germans, on the other hand, was partly due to the fact that they rushed at the Arabs blindly and attempted to deal with them in a brutally direct manner.

Whenever a new shereef or sheik came for the first time to offer his services to King Hussein, Lawrence and any other British officer present made it a point to leave the emir’s tent until the formality of swearing allegiance on the Koran and touching Feisal’s hand was over. They did this because the strange sheik might easily become suspicious if his first impression revealed foreigners in Feisal’s confidence. At the same time it was Lawrence’s policy always to have his name associated with those of the shereefs. Everywhere he went he was regarded as Feisal’s mouthpiece. “Wave a shereef in front of you like a banner and hide your own mind and person,” was the maxim of this student of Bedouin tactics. But Lawrence was careful not to identify himself too long or too often with any one tribal sheik, for he did not want to lose prestige by being associated with any particular tribe and its inevitable feuds. The Bedouins are extremely jealous. When going on an expedition Lawrence would ride with every one up and down the line, so that no one could criticize him for showing favoritism.

In every way Lawrence used his knowledge of desert psychology to the best possible advantage. For instance, he was constantly in need of detailed information regarding the topography of the country over which the Arabian forces were campaigning; but the Bedouins are always reluctant to reveal the location of wells, springs, and points of vantage. Lawrence convinced them that making maps was an accomplishment of every educated man. Auda Abu Tayi and many of the other sheiks became so keenly interested in maps that they often kept Lawrence up to all hours of the night helping them with maps that were not of the slightest military value and in which he was not in the least interested.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on How to Handle Arabs by Lowell Thomas from his book With Lawrence in Arabia published in 1924. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on How to Handle Arabs here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.