The reader has but to turn to the debates of 1816 to discover that the discussion of the tariff bill turned entirely on its protective character and that Calhoun was the special defender of its protective provisions.

Continuing The South Carolina Nullification Crisis,

our selection from Life of Andrew Jackson by James Parton published in 1860. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The South Carolina Nullification Crisis.

Time: 1832

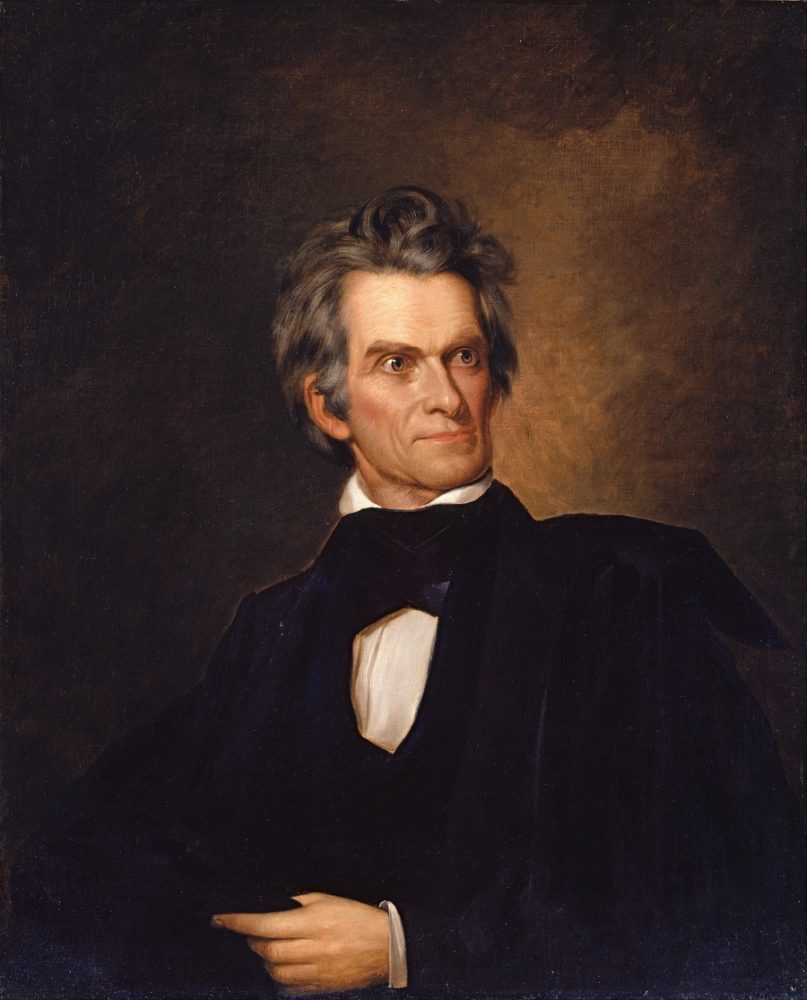

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The essay is divided into two parts. First, the Vice-President endeavors to show that nullification is the natural, proper, and peaceful remedy for an intolerable grievance inflicted by Congress upon a State or upon a section; secondly, that the Tariff Law of 1828, unless rectified during the next session of Congress, will be such a grievance. He went all lengths against the the protective principle. It was unconstitutional, unequal in its operation, oppressive to the South, an evil “inveterate and dangerous.” The reduction of duties to the revenue standard could be delayed no longer ” without the most distracting and dangerous consequences.

The honest and obvious course is to prevent the accumulation of the surplus in the treasury by a timely and judicious reduction of the imposts, and thereby to leave the money in the pockets of those who made it, and from whom it cannot be honestly nor constitutionally taken unless required by the fair and legitimate wants of the Government.

If, neglecting a disposition so obvious and just, the Government should attempt to keep up the present high duties when the money was no longer wanted, or to dispose of this immense surplus by enlarging the old or devising new schemes of appropriations; or, finding that to be impossible, it should adopt the most dangerous, unconstitutional, and absurd project ever devised by any Government, of dividing the surplus among the States —- a project which, if carried into execution, could not fail to create an antagonistic interest between the States and General Government on all questions of appropriations, which would certainly end in reducing the latter to a mere office of collection and distribution — either of these modes would be considered by the section suffering under the present high duties as a fixed de termination to perpetuate forever what it considers the present unequal, unconstitutional, and oppressive burden; and from that moment it would cease to look to the General Government for relief. “

Nullification is distinctly announced in this passage. It seems to be again announced, as a thing inevitable, in the concluding words of the essay:

In thus placing my opinions before the public I have not been actuated by the expectation of changing the public sentiment. Such a motive, on a question so long agitated and so beset with feelings of prejudice and interest, would argue on my part an insufferable vanity and a profound ignorance of the human heart. To avoid as far as possible the imputation of either, I have confined my statements on the many and important points on which I have been compelled to touch, to a simple declaration of my opinion, without advancing any other reasons to sustain them than what appeared to me to be indispensable to the full understanding of my views.

With every caution on my part I dare not hope, in taking the step I have, to escape the imputation of improper motives; though I have without reserve freely expressed my opinions, not regarding whether they might or might not be popular. I have no reason to believe that they are such as will conciliate public favor, but the opposite; which I greatly regret, as I have ever placed a high estimate on the good opinion of my fellow citizens. But, be this as it may. I shall at least be sustained by feelings of conscious rectitude. I have formed my opinions after the most careful and deliberate examination, with all the aids which my reason and experience could furnish; I have expressed them honestly and fearlessly, regardless of their effects personally; which, however interesting to me individually, are of too little importance to be taken into the estimate where the liberty and happiness of our country are so vitally involved.”

In this performance Calhoun did not refer to his forgotten championship of the protective policy in 1816. The busy burrowers of the press, however, occasionally brought to the surface a stray memento of that championship, which the press of South Carolina denounced as slanderous. A Mr. Reynolds, of South Carolina, was moved, by his disgust at such reminders, to write to Calhoun, asking him for information respecting “the origin of a system so abhorrent to the South.” Calhoun, replying to the inquiry, said that “he had always considered the tariff of 1816 as in reality a measure of revenue — as distinct from one of protection”; that it reduced duties instead of increasing them; that the protection of manufactures was regarded as a mere incidental feature of the bill; that he had regarded its protective character as temporary, to last only until the debt should be paid; that in fact he had not paid very particular attention to the details of the bill at the time, as he was not a member of the committee that had drawn it; that “his time and attention were much absorbed with the question of the currency,” as he was chairman of the committee on that subject; that the Tariff Bill of 1816 was innocence itself compared with the monstrous and unconstitutional tariff of 1828, and had no principle in common with it.

These assertions may not all be destitute of truth, but the impression created by them is most erroneous. The reader has but to turn to the debates of 1816 to discover that the discussion of the tariff bill turned entirely on its protective character and that Calhoun was the special defender of its protective provisions. The strict constructionist or State Rights party was headed then in the House by John Randolph, who, on many occasions during the long debate, rose to refute Calhoun’s protective reasoning. Calhoun was then a member of the other wing of the Republican party. He was a bank man, an internal improvement man, a protectionist, a consolidationist — in short, a Republican of the Hamiltonian school, rather than the Jeffersonian. He was strenuous in asserting, among other things, that protection would benefit the planter as much as it benefited the manufacturer. In fact, there is no protective argument that can not be found in the speeches of Calhoun upon the tariff of 1816. Indeed, it was Calhoun’s course on this question in 1816 which gave him that popularity in Pennsylvania which induced his friends in that State to start him for the Presidency in 1824. His principal tariff speech had been printed upon a sheet, framed, hung up in bar rooms and parlors along with the Farewell Address of General Washington. A Member of Congress from Pennsylvania reminded Calhoun of this fact during the session of 1833.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.