This series has four easy 5-minute installments. This first installment: Diligent Study of Everyday Habits.

Introduction

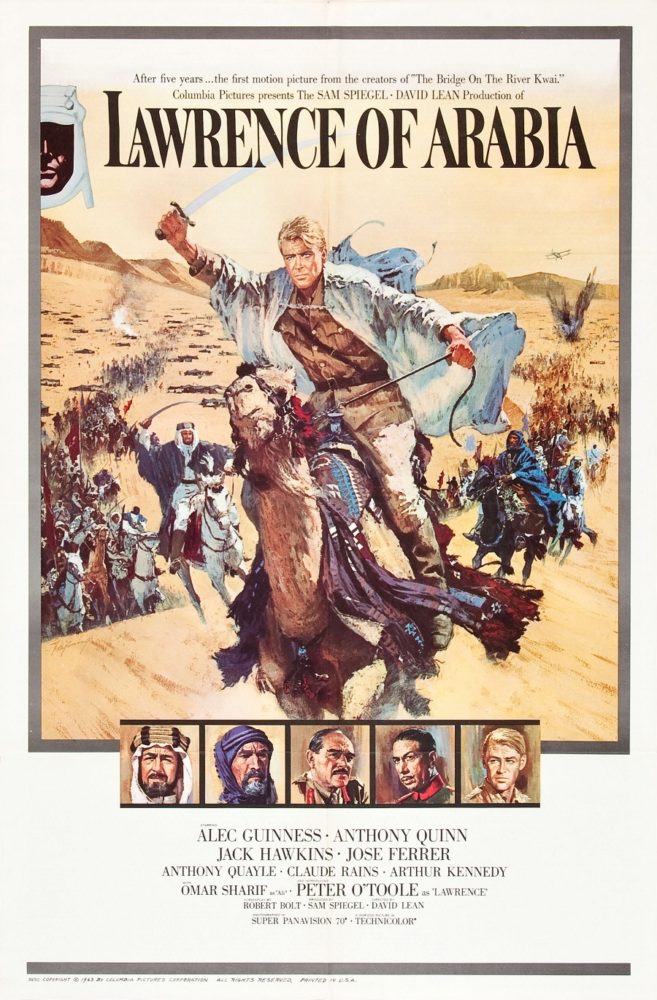

The enigmatic and exotic Lawrence of Arabia is the basis of this series. He was a British officer who led the Arab peoples in revolt against the Ottomans during World War I. This series summarizes lessons learned.

This selection is from With Lawrence in Arabia by Lowell Thomas published in 1924. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Lowell Thomas (1892-1981) was an American writer and broadcaster. He was television’s first news anchor.

Time: World War I

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Colonel Lawrence believed in the Arabs, and the Arabs believed in him, but they would never have trusted him so implicitly had he not been such a complete master of their customs and all the superficial external features of Arabian life. I once asked him, when we were trekking across the desert, what he considered the best way of dealing with the wild nomad peoples of this part of the world. My motive was to try to get him to tell in his own words something about the methods that had enabled him to accomplish what no other man could. I am confident that he thought I wanted the information merely for my own immediate use in dealing with the Bedouins with whom we were living. Had he suspected that I was attempting to make him talk about himself, he would have turned the conversation into other channels.

“The handling of Arabs might be termed an art, not a science, with many exceptions and no obvious rules,” was his answer. “The Arab forms his judgment on externals that we ignore, and so it is vitally important that a stranger should watch every movement he makes and every word he says during his first weeks of association with a tribe. Nowhere in the world is it so difficult to atone for a bad start as with the Bedouins. However, if you once succeed in reaching the inner circle of a tribe and actually gain their confidence, you can do pretty much as you please with them and at the same time do many things yourself that would have caused them to regard you as an outcast had you been too forward at the start. The beginning and end of the secret of handling Arabs is an unremitting study of them. Always keep on your guard; never speak an unnecessary word; watch yourself and your companions constantly; hear all that passes; search out what is going on beneath the surface; read the characters of Arabs; discover their tastes and weaknesses and keep everything you find out to yourself. Bury yourself in Arab circles; have no ideas and no interests except the work in hand, so that you master your part thoroughly enough to avoid any of the little slips that would counteract the painful work of weeks. Your success will be in proportion to your mental effort.”

To illustrate the importance the Bedouins place on externals, Lawrence told me that on one occasion a British officer went up country; and the first night, as the guest of a Howeitat sheik, he sat down on the guest rug of honor with his feet stretched out in front of him instead of tucked under him in Arab fashion. That officer was never popular with the Howeitat. To the Bedouin it is as offensive to display the pedal extremities ostentatiously as it would be for us to put our feet on the table at a dinner-party. A short distance behind us in the caravan rode a chief of the Shammar Arabs who had a great scar across his face. Lawrence related this story:

“While that fellow was dining with Ibn Rashid, the ruler of North Central Arabia, he happened to choke. He felt so much humiliated that he jerked out his knife and slit his mouth right up to the carotid artery in his cheek, merely to show his host that a bit of meat had actually stuck in his back teeth.”

The Arabs consider it a sign of very bad breeding for a man to choke over his food. Not only does it show that he is greedy, but it is believed that the devil has caught him. Other fine points of etiquette are bound up in the fact that the Bedouins never use forks and knives, but simply reach into the various dishes on the table with their hands. For instance, it is extremely bad form for any one to eat with his left hand.

The dyed-in-the-wool nomad of Arabia never makes allowances for any ignorance of desert customs in forming his judgment of a stranger. If you have not mastered desert etiquette, you are regarded as an alien and perhaps hostile outsider. Lawrence’s understanding of the Arabs and his unfailing ability to do the right thing at the right moment was uncanny. Of course, he could not have lived as an Arab in Arabia if he had not learned the family history of all the prominent peoples of the desert, including the complete list of their friends and enemies. He was expected to know that a certain man’s father had been hanged or that his mother was the divorced wife of some famous chieftain. It would be as awkward to inquire about an Arab’s father if he had been a famous fighter as it would be to introduce a divorced woman to her former husband. If Lawrence desired any information he gained it by indirect means and by cleverly leading the conversation around to the subject in which he was interested; he never asked questions. Fortunately for the Arab Nationalist movement and for the Allies, Lawrence had got beyond the stage of making mistakes before the war and at one time was actually a sheik of a tribe in Mesopotamia.

“It is vitally important for any one dealing with the desert peoples to speak their local dialects, not the Arabic current in some other part of the East,” declared Lawrence. “The safest plan is to be rather formal at first, to avoid getting too deeply involved in conversation.” Nearly all the officers sent to cooperate with the Arabs in the revolt spoke the Egyptian-Arabic dialect. The Arabs despise the Egyptians, whom they regard as poor relations Therefore, most of the Europeans sent by the Allies to cooperate with the Hedjaz people found themselves coldly treated. The Allies succeeded in winning the Arabs to their cause because Lawrence was able to crystallize the Arabian idea of winning independence from the Turks into a definite form and because he had attained the unusual distinction of being taken into the bosom of most of their tribes.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.