But darker and larger and mightier spread the cloud above them. It was a sudden and more ghastly Night rushing upon the realm of Noon!

Continuing Volcano Buries Pompeii.

Today we begin the second part of the series with our selection from The Last Days of Pompeii by Edward Bulwer-Lytton published in 1834. The selection is presented in 2 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873) was an English writer and politician becoming a cabinet minister in 1858.

Previously in Volcano Buries Pompeii.

Time: October or November 79 AD

Place: Pompeii, Italy

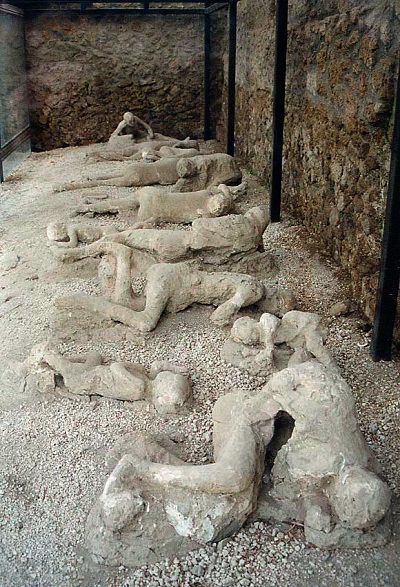

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The Amphitheatre at Pompeii was crowded to the doors. A lion was at large in the arena, and the populace surged toward an Egyptian priest, Arbaces, demanding that he be thrown down to be devoured. As the mob rolled around him, intent on his death, Arbaces noted a strange and awful apparition. His craft made him courageous; he stretched forth his hand.

“Behold!” he shouted with a voice of thunder, which stilled the roar of the crowd; “behold how the gods protect the guiltless! The fires of the avenging Orcus burst forth against the false witness of my accusers!”

The eyes of the crowd followed the gesture of the Egyptian, and beheld, with ineffable dismay, a vast vapor shooting from the summit of Vesuvius, in the form of a gigantic pine tree; the trunk, blackness — the branches, fire! — a fire that shifted and wavered in its hues with every moment, now fiercely luminous, now of a dull and dying red, that again blazed terrifically forth with intolerable glare!

There was a dead, heart-sunken silence — through which there suddenly broke the roar of the lion, which was echoed back from within the building by the sharper and fiercer yells of its fellow-beast. Dread seers were they of the burden of the atmosphere, and wild prophets of the wrath to come!

Then there arose on high the universal shrieks of women; the men stared at each other, but were dumb. At that moment they felt the earth shake beneath their feet; the walls of the theatre trembled, and beyond, in the distance, they heard the crash of falling roofs; an instant more and the mountain-cloud seemed to roll toward them, dark and rapid, like a torrent; at the same time it cast forth from its bosom a shower of ashes mixed with vast fragments of burning stone. Over the crushing vines — over the desolate streets — over the Amphitheatre itself — far and wide — with many a mighty splash in the agitated sea — fell that awful shower!

No longer thought the crowd of justice or of Arbaces; safety for themselves was their sole thought. Each turned to fly — each dashing, pressing, crushing, against the other. Trampling recklessly over the fallen — amid groans and oaths and prayers and sudden shrieks, the enormous crowd vomited itself forth through the numerous passages. Whither should they fly? Some, anticipating a second earthquake, hastened to their homes to load themselves with their more costly goods, and escape while it was yet time; others, dreading the showers of ashes that now fell fast, torrent upon torrent, over the streets, rushed under the roofs of the nearest houses or temples or sheds — shelter of any kind — for protection from the terrors of the open air. But darker and larger and mightier spread the cloud above them. It was a sudden and more ghastly Night rushing upon the realm of Noon!

Meanwhile the streets were already thinned; the crowd had hastened to disperse itself under shelter; the ashes began to fill up the lower parts of the town; but, here and there, you heard the steps of fugitives cranching them warily, or saw their pale and haggard faces by the blue glare of the lightning or the more unsteady glare of torches, by which they endeavored to steer their steps. But ever and anon the boiling water, or the straggling ashes, mysterious and gusty winds, rising and dying in a breath, extinguished these wandering lights, and with them the last living hope of those who bore them.

Amid the other horrors, the mighty mountain now cast up columns of boiling water. Blent and kneaded with the half-burning ashes, the streams fell like seething mud over the streets in frequent intervals. And full, where the priests of Isis had now cowered around the altars, on which they had vainly sought to kindle fires and pour incense, one of the fiercest of those deadly torrents, mingled with immense fragments of scoria, had poured its rage. Over the bended forms of the priests it dashed: that cry had been of death — that silence had been of eternity! The ashes — the pitchy stream — sprinkled the altars, covered the pavement, and half concealed the quivering corpses of the priests!

In proportion as the blackness gathered did the lightnings around Vesuvius increase in their vivid and scorching glare. Nor was their horrible beauty confined to the usual hues of fire; no rainbow ever rivalled their varying and prodigal dyes. Now brightly blue as the most azure depth of a southern sky — now of a livid and snakelike green, darting restlessly to and fro as the folds of an enormous serpent — now of a lurid and intolerable crimson, gushing forth through the columns of smoke, far and wide, and lighting up the whole city from arch to arch — then suddenly dying into a sickly paleness, like the ghost of their own life!

In the pauses of the showers you heard the rumbling of the earth beneath and the groaning waves of the tortured sea; or, lower still, and audible but to the watch of intensest fear, the grinding and hissing murmur of the escaping gases through the chasms of the distant mountain. Sometimes the cloud appeared to break from its solid mass, and, by the lightning, to assume quaint and vast mimicries of human or of monster shapes, striding across the gloom, hurtling one upon the other, and vanishing swiftly into the turbulent abyss of shade; so that to the eyes and fancies of the affrighted wanderers the unsubstantial vapors were as the bodily forms of gigantic foes — the agents of terror and of death.

The ashes in many places were already knee-deep; and the boiling showers which came from the steaming breath of the volcano forced their way into the houses, bearing with them a strong and suffocating vapor. In some places immense fragments of rock, hurled upon the house roofs, bore down along the streets masses of confused ruin, which yet more and more, with every hour, obstructed the way; and, as the day advanced, the motion of the earth was more sensibly felt — the footing seemed to slide and creep — nor could chariot or litter be kept steady, even on the most level ground.

Sometimes the huger stones, striking against each other as they fell, broke into countless fragments, emitting sparks of fire, which caught whatever was combustible within their reach; and along the plains beyond the city the darkness was now terribly relieved, for several houses, and even vineyards, had been set on flames; and at various intervals the fires rose sullenly and fiercely against the solid gloom. To add to this partial relief of the darkness, the citizens had, here and there, in the more public places, as the porticoes of temples and the entrances to the forum, endeavored to place rows of torches; but these rarely continued long; the showers and the winds extinguished them, and the sudden darkness into which their sudden birth was converted had something in it doubly terrible and doubly impressing on the impotence of human hopes, the lesson of despair.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Pliny began here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.