We discover, therefore, that while the President was resolved to crush nullification by force if it opposed by force the collection of the revenue, he was also disposed to concede to nullification all that its more moderate advocates demanded.

Continuing The South Carolina Nullification Crisis,

our selection from Life of Andrew Jackson by James Parton published in 1860. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The South Carolina Nullification Crisis.

Time: 1832

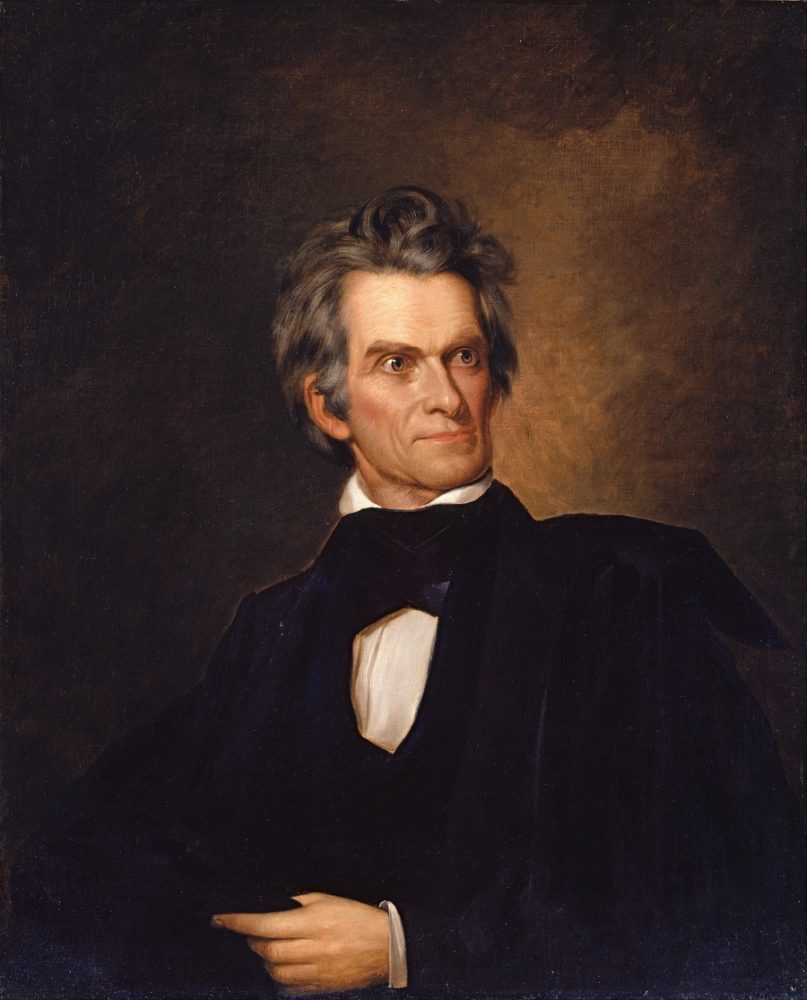

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Calhoun was in his place in the Senate-Chamber when Congress convened. He had arrived two weeks before, after a journey which one of his biographers compares to that of Luther to the Diet of Worms. He met averted faces and estranged friends everywhere on his route, we are told. Only now and then some daring man found courage to whisper in his ear, “If you are sincere, and are sure of your cause, go on, in God’s name, and fear nothing.” Washington was curious to know, we are further assured, what the Arch-Nullifier would do when the oath to support the Constitution of the United States was proposed to him. “The floor of the Senate-Chamber and the galleries were thronged with spectators. They saw him take the oath with a solemnity and dignity appropriate to the occasion, and then calmly seat himself on the right of the Chair, among his old political friends, nearly all of whom were now arrayed against him.”

After the President’s message had been read, Calhoun rose to vindicate himself and his State, which he did with that singular blending of subtlety and force which characterized his later efforts. He declared himself still devoted to the Union, and said that if the Government were restored to the principles of 1798 he would be the last man in the country to question its authority.

.

February 1st, the dreaded day which was to be the first of a fratricidal war, went by, and yet no hostile and no nullifying act had been done in South Carolina. How was this? Did those warlike words mean nothing? Was South Carolina repentant? The President was resolved, and avowed his resolve, that the hour which brought the news of one act of violence on the part of the Nullifiers should find Calhoun a prisoner of state upon a charge of high treason — and not Calhoun only, but every Member of Congress from South Carolina who had taken part in the proceedings which had caused the conflict between South Carolina and the General Government.

Whether this intention of the President had any effect upon course of events, we cannot know. It came to pass, that, a few days before February 1st. a meeting of the leading Nullifiers was held in Charleston, who passed resolutions to this effect: that, inasmuch as measures were then pending in Congress which contemplated the reduction of duties demanded by South Carolina, the nullification of the existing revenue laws should be postponed until after the adjournment of Congress; when the convention would reassemble, and take into consideration whatever revenue measures may have been passed by Congress. The session of 1833 being the “short” session, ending necessarily on March 4th. the Union was respited thirty-two days by the Charleston meeting.

The President, in his annual message, recommended Congress to subject the tariff to a new revision, and to reduce the duties so that the revenue of the Government, after the payment of the public debt, should not exceed its expenditures. He also recommended that, in regulating the reduction, the interests of the manufacturers should be duly considered. We discover, therefore, that while the President was resolved to crush nullification by force if it opposed by force the collection of the revenue, he was also disposed to concede to nullification all that its more moderate advocates demanded. Accordingly, McLane, the Secretary of the Treasury, with the assistance of Gulian C. Verplanck, of New York, and other Administration members, prepared a new tariff bill, which provided for the reduction of duties to the revenue standard, and which was deemed by its authors as favorable to the manufacturing interest as the circumstances permitted.

This bill, reported by Verplanck on December 28th. and known as the Verplanck Bill, was calculated to reduce the revenue thirteen million dollars, and to afford to the manufacturers about as much protection as the tariff of 1816 had given them. It put back the “American System,” so to speak, seventeen years. It destroyed nearly all that Clay and the protectionists had effected in 1820, 1824, 1828, and 1832. Is it astonishing that the manufacturers were panic-stricken ? Need we wonder that, during the tariff discussions of 1833, two Congresses sat in Washington, one in the Capitol, composed of the Representatives of the people, and another outside of the Capitol, consisting of representatives of the manufacturing interest? Was it not to be expected that Clay, seeing the edifice which he had constructed with so much toil and talent about to tumble into ruins, would be willing to consent to any measure which could even postpone the catastrophe?

The Verplanck Bill made slow progress. The outside pressure against it was such that there seemed no prospect of its passing. The session was within twenty days of its inevitable termination. The bill had been debated and amended, and amended and debated, and yet no apparent progress had been made toward that conciliation of conflicting interests without which no tariff bill whatever can pass. The dread of civil war, which overshadowed the Capitol, seemed to lose its power as a legislative stimulant, and there was a respectable party in Congress, led by Webster, who thought that all tariff legislation was undignified and improper while South Carolina maintained her threatening attitude. The Constitution, Webster maintained, was on trial. The time had come to test its reserve of self-supporting power. No compromise, no concession, said he, until the nullifying State returns to her allegiance.

No question of so much importance as this can be discussed in Congress without a constant, secret reference to its effect upon the next Presidential election. “It is mortifying, inexpressibly disgusting,” wrote Clay to Judge Brooke, in the midst of the debate upon his own compromise bill of this session,

to find that considerations affecting an election now four years distant in fluence the fate of great questions of immediate interest more than all the reasons and arguments which intimately appertain to those questions. If, for example, the tariff now before the House should be lost, its defeat will be owing to two causes: First, the apprehension of Van Buren’s friends that, if it passes, Calhoun will rise again as the successful vindicator of Southern rights. Second, its passage might prevent the President from exercising certain vengeful passions which he wishes to gratify in South Carolina. And if it passes, its passage may be attributed to the desire of those same friends of Van Buren to secure Southern votes.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.