Today’s installment concludes The South Carolina Nullification Crisis,

our selection from Life of Andrew Jackson by James Parton published in 1860.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of seven thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The South Carolina Nullification Crisis.

Time: 1832

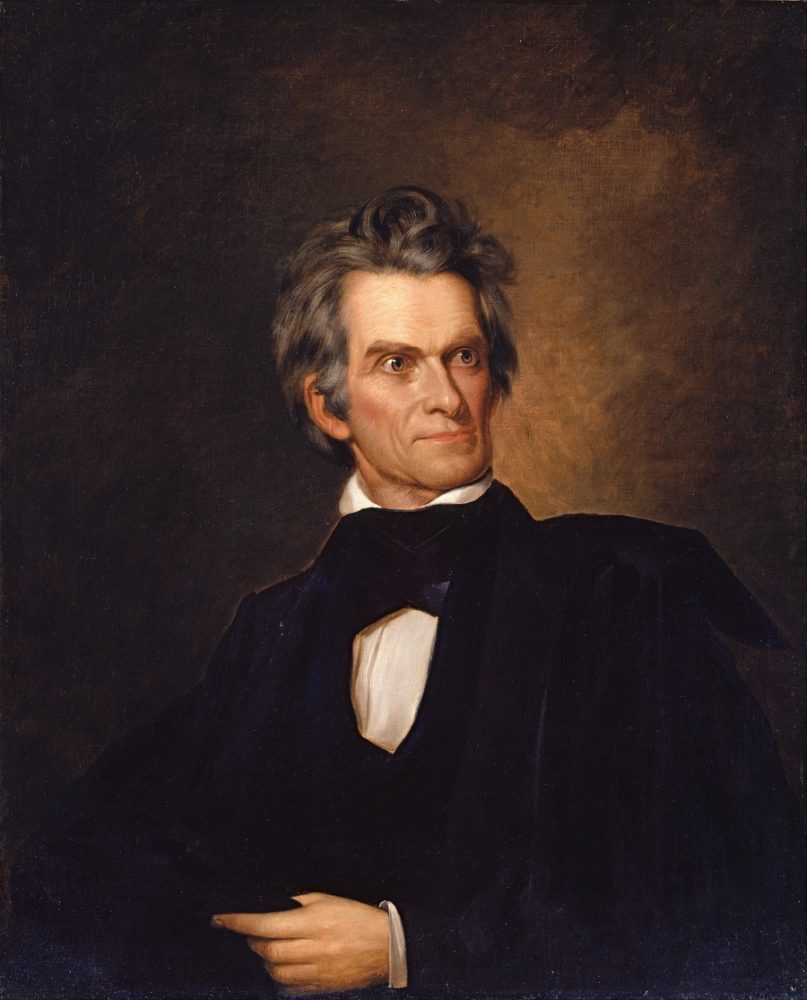

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The closing struggle between policy and principle let our eyewitness, Colonel Benton, describe:

Clayton being inexorable in his claims, Clay and Calhoun agreed to the amendments, and all voted for them, one by one, as Clay offered them, until it came to the last -— that revolting measure of the home valuation. As soon as it was proposed, Calhoun and his friends met it with violent opposition, declaring it to be unconstitutional, and an insurmountable obstacle to their votes for the bill if put into it. It was then late in the day, the last day but one of the session and Clayton found himself in the predicament which required the execution of his threat to table the bill. He executed it and moved to lay it on the table, with the declaration that it was to lie there. Clay went to him and besought him to withdraw the motion; but in vain – he remained inflexible; and the bill then appeared to be dead. In this extremity, the Calhoun wing retired to the colonnade behind the Vice-President’s chair, and held a brief consultation among themselves; and presently Bibb, of Kentucky, came out and went to Clayton and asked him to withdraw his motion to give him time to consider the amendment. Seeing this sign of yielding, Clayton withdrew his motion to be renewed if the amendment was not voted for.

A friend of the parties immediately moved an adjournment, which was carried; and that night’s reflections brought them to the conclusion that the amendment must be passed, but still with the belief that, there being enough to pass it without him, Calhoun should be spared the humiliation of appearing on the record in its favor. This was told to Clayton, who declared it to be impossible; that Calhoun’s vote was indispensable, as nothing would be considered secured by the passage of the bill unless his vote appeared for every amendment separately, and for the whole bill collectively. When the Senate met, and the bill was taken up, it was still unknown what he would do; but his friends fell in, one after the other, yielding their objections upon different grounds, and giving their assent to this most flagrant instance (and that a new one) of that protective legislation against which they were then raising troops in South Carolina ! and limiting a day, and that a short one, on which she was to be, ipso facto, a seceder from the Union.

Calhoun remained to the last, and only rose when the vote was ready to be taken, and prefaced a few remarks with the very notable declaration that he had then to determine which way he would vote. He then declared in favor of the amendment, but upon conditions which he desired the reporters to note, and which, being futile in themselves, only showed the desperation of his condition, and the state of impossibility to which he was reduced. Several Senators let him know immediately the futility of his conditions; and without saying more, he voted on ayes and noes for the amendment, and afterward for the whole bill. “

The Compromise Bill, which passed in the Senate by a vote of twenty-nine to sixteen, was sprung upon the House of Representatives, and carried in that body by a coup-de-main. The Verplanck Bill, Colonel Benton indignantly informs us, was afloat in the House, “upon the wordy sea of stormy debate,” as late as February 25th. “All of a sudden,” he continues,

it was arrested, knocked over, run under, and merged and lost in a new one, which expunged the old one and took its place. It was late in the afternoon when Letcher, of Kentucky, the fast friend of Clay, rose in his place, and moved to strike out the whole Verplanck Bill — every word except the enacting clause — and insert, in lieu of it, a bill offered in the Senate by Clay, since called the ‘Compromise.’ This was offered in the House without notice, without signal, without premonitory symptom, and just as the members were preparing to adjourn. Some, taken by surprise, looked about in amazement; but the majority showed consciousness, and, what was more, readiness for action.

The bill, which made its first appearance in the House when members were gathering up their overcoats for a walk home to their dinners, was passed before those coats had got on their backs; and the dinner which was waiting had but little time to cool before the astonished members, their work done, were at the table to eat it. A bill without precedent in the annals of our legislation, and pretending to the sanctity of a compromise, and to settle great questions forever, went through to its consummation in the fragment of an evening session, without the compliance with any form which experience and parliamentary law have devised for the safety of legislation.”

The bill passed in the House by a vote of one hundred nineteen to eighty-five.

That the President disapproved of this hasty and, as the event proved, unstable compromise is well known. The very energy with which Colonel Benton denounces it shows how hateful it was to the Administration. President Jackson, however, signed the bill concocted by his enemies. It would have been more like him to have vetoed it and I do not know why he did not veto it. The time may come when the people of the United States will wish he had vetoed it, and thus brought to an issue, and settled finally, a question which, at some future day, may assume more awkward dimensions, and the country have no Jackson to meet it.

[This was written a year or two before the Civil War.-ED.]

Calhoun left Washington, and journeyed homeward post haste, after Congress adjourned. “Travelling night and day, by the most rapid public conveyances, he succeeded in reaching Columbia in time to meet the convention before they had taken any additional steps. Some of the more fiery and ardent members were disposed to complain of the Compromise Act, as being only a half-way, temporizing measure; but when his explanations were made, all felt satisfied, and the convention cordially approved of his course. The Nullification Ordinance was repealed (March, 1833), and the two parties in the State abandoned their organizations, and agreed to forget all their past differences.” So the storm blew over.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The South Carolina Nullification Crisis by James Parton from his book Life of Andrew Jackson published in 1860. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The South Carolina Nullification Crisis here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.