This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Capture or Destroy the Spanish Fleet.

Introduction

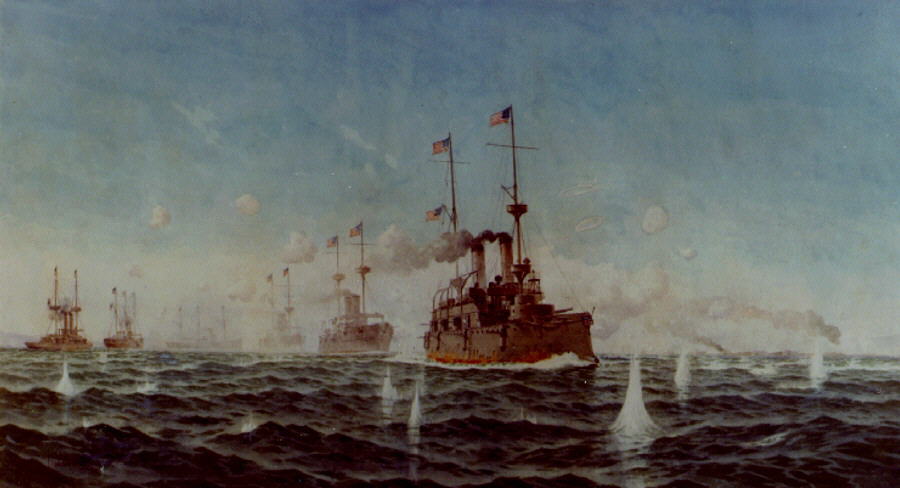

One of the world-wide surprises of modern times occurred on May day, 1898, when an American fleet sailed into a bay on the other side of the globe, annihilated the fleet of a European Power, and added an immense domain to the territory of the United States. It is a singular fact that the law of neutrality, applicable to naval warfare, instead of protecting a weaker Power, created an advantage for a stronger one. For when Dewey, on the declaration of war, was ordered to leave the neutral port of Hong Kong, there was nothing for him to do but capture a port from the enemy, hence his prompt action in sailing for Manila. The greater and more spectacular surprise was his sinking of the entire Spanish fleet without the loss of a vessel or a man. This was due, first to the superiority of the American armament, and secondly to the vast superiority of American marksmanship. The United States Navy Department had for some time made liberal allowance of ammunition for target-practice and had given the gunners money prizes for the best shots. Hence when they fired at anything they seldom failed to hit it; while the brave but unskillful Spaniards, as one American captain expressed it, could hardly hit anything but the water.

Of many accounts of that consequential battle, one of the best, written by the eminent historian, Hubert Howe Bancroft, has been chosen for presentation here.

This selection is from The New Pacific by Hubert Howe Bancroft published in 1900. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Hubert Howe Bancroft (1832-1918) was a historian and a publisher. He published 39 volumes on the history of the old west in America.

Time: May 1, 1898

Place: Manila Bay, Philippines

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

“Capture or destroy the Spanish fleet,” said the President.

“I will wipe it from the ocean,” the Commodore replied.

With these words was initiated a new era in the world’s development, involving a course of events broad in influence as the earth and as far – reaching as time. The place was Mirs Bay, near Hong Kong, and the day was April 26, 1898.

War for the deliverance of Cuba had been declared, but the world was hardly looking for the first demonstration to appear on the coast of Asia. Commodore George Dewey, however, in command of the United States squadron at Hong Kong, had been momentarily expecting some such word from the President ever since the breaking off of diplomatic relations with Spain on April 21st, though war was not declared until the 25th. The squadron had withdrawn from Hong Kong at the request of the Governor General.

Dewey was ready. He had been in command of the Asiatic squadron since January, had thought matters well over, and his plans were fully matured. A coat of war – paint had been given the ships, and the White Squadron had changed in color to a dark drab. A cargo of coal which had lately arrived in the British steamer Nanshan from Cardiff, had been bought, with the ship that carried it, care having been taken to make this purchase before the beginning of hostilities and the declaration of England’s neutrality should prevent it. The steamer Zafiro, of the Manila and Hong Kong line, was also purchased, and the spare ammunition placed on board of her, the crews of both vessels being reshipped under the United States flag.

The American fleet consisted of nine ships — four protected cruisers of the second class, two gunboats, one revenue cutter, and two transports (the Olympia, flagship, Captain C. V. Gridley; Boston, Captain F. Wildes; Raleigh, Captain J. B. Coghlan; Baltimore, Captain N. M. Dyer; Concord, Commander A. S. Walker; Petrel, Commander E. P. Wood; and the revenue cutter McCulloch). In Manila harbor was the Spanish fleet of sixteen vessels, Admiral Montojo, comprising seven wood – and iron cruisers, five gunboats, two torpedo boats, and two transports. The cruisers were La Reina Cristina, flagship, Castilla, Don Antonio de Ulloa, Don Juan de Austria, Isla de Luzon, Isla de Cuba, and Velasco. The Americans had the better ships and guns; the Spaniards had more ships, a protecting port, and shore batteries. There was not an armored vessel in either squadron.

President McKinley’s telegram was brought to Commodore Dewey from Hong Kong by the cutter. The news spread among officers and seamen, and a wild cheer went up from those waters as the Commodore’s signal appeared calling his captains to the flagship to receive their instructions. On the day following the fleet steamed away for the Philippines, six hundred twenty-eight miles distant.

Not knowing to a certainty just where the enemy might be found, on approaching the Philippines Dewey called at Bolinao Bay, and again at Subig Bay, the latter thirty miles from Manila; but the Spanish warships were not there. Copies of a Spanish newspaper were obtained by several of the officers, in which was a characteristic communication, dated April 23rd, by the Commander-in-Chief at Manila, General Augustin, full of bombast and braggadocio, and calling the Americans bad names, as in famous cowards who burned towns, pillaged churches, sacked convents, tortured prisoners, and killed women and children. In this strain he continues:

The North American people, constituted of all the social excrescences, have exhausted our patience and provoked war with their perfidious machinations, with their acts of treachery, with their outrages against the law of nations and international conventions. The struggle will be short and decisive. The God of victories will give us one as brilliant as the justice of our cause demands. Spain, which counts upon the sympathies of all nations, will emerge triumphantly from this new test, humiliating and blasting the adventurers from those States which, without cohesion and without a history, offer to humanity only infamous traditions and the ungrateful spectacle of a legislature in which appear united insolence and defamation, cowardice and cynicism.

A squadron manned by foreigners, possessing neither instruction nor discipline, is preparing to come to this archipelago with the ruffianly intention of robbing us of all that means life, honor, and liberty. Filipinos, prepare for the struggle, and, united under the glorious Spanish flag, which is ever covered with laurels, let us fight with the conviction that victory will crown our efforts, and to the challenge of our enemies let us oppose, with the decision of the Christian and the patriot, the cry of Viva España!

Your General, Basilio Augustin Davila”

The fleet arrived off Manila Saturday evening, April 30th. The night came on hot and stilling. The guns were all loaded, and a supply of shot was placed ready at hand. After a slight shower the moon shone soft through the haze, thus enabling the men to see without the searchlights. Not one of the officers on any of those ships had ever been in this harbor before. In all their desperate undertaking, in all the emergencies and rapid movements of the fight, they must be directed only by charts.

The bay is oval; at the entrance is Corregidor Island, and at the farther end the city of Manila, twenty-six miles from the entrance. The town of Cavité, where were the military post and marine arsenal, and under whose guns the Spanish fleet lay, is ten miles nearer. On the spit opposite Cavité was a large mortar battery. Manila Bay was Spain’s stronghold in the Orient, reported impregnable, the entrance well mined, and the borders bristling with Krupp guns.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.