Today’s installment concludes The Battle of Manila Bay,

our selection from The New Pacific by Hubert Howe Bancroft published in 1900.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Battle of Manila Bay.

Time: May 1, 1898

Place: Manila Bay, Philippines

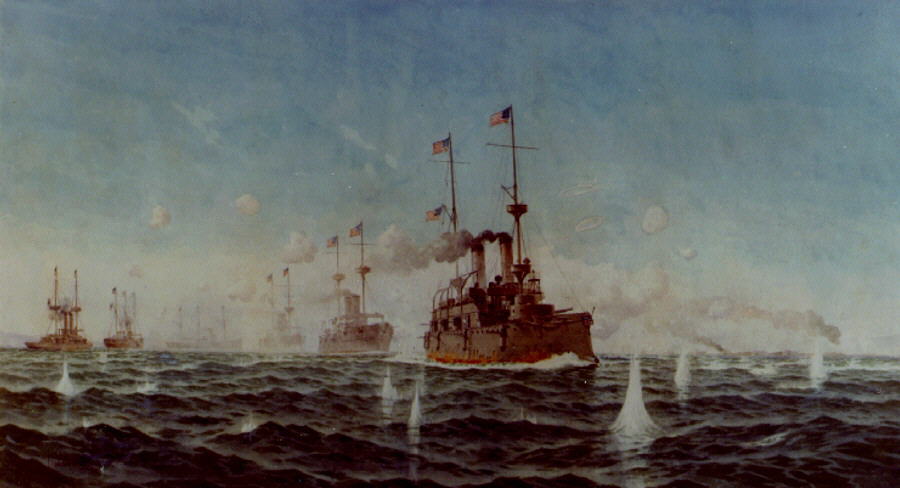

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

At a quarter before eleven the engagement was renewed and an hour later the work of destruction was complete and still with out the loss of a single American. In this second part of the battle, essentially the same line of tactics was followed. This time the Baltimore took the lead; and the orders were to clean up as they went along; that is, all were to concentrate their fire on each Spanish ship as they came to it, and complete its destruction before proceeding to the next. Thus the finishing stroke was first given to La Reina Cristina, which soon blew up and sank. Attacked simultaneously by the Baltimore, Raleigh, and Olympia, the Don Juan de Austria received a shell in her magazine, which exploded, and the vessel sank.

The signal was then given, “Destroy the fortifications,” and the Baltimore, steaming within two thousand five hundred yards of the forts, poured in broadsides with great precision and terrible effect. Lying close in shore was a Spanish cruiser. The Concord, soon joined by the Olympia, darted after her, and threw eight-inch shells into her until she took fire. The Don Antonio de Ulloa, lying inside the mole, kept up a continuous fire until an eight-inch shell struck her waterline amidships, and she went down stern first with colors flying. And so with the others; all were either burned or sunk, the Spaniards themselves setting on fire and scuttling several of their own ships. At length a white flag appeared fluttering over the arsenal, and instantly the signal was given, “Cease firing.” Montojo reported his loss at three hundred eighty-one killed or wounded.

The Spaniards fought with courage and devotion, but the conditions which gave success to the Americans were not present with the Spaniards. Their ships were old, their guns were poor, and their men lacked the training and discipline that secure efficiency. In obedience to the commands of vain and selfish rulers, they did what they could; they went down to their death asking no quarter, every ship sinking with its flags flying. Without considering the loss of empire, the day’s destruction represented, as was estimated, a loss to the Spaniards in monetary value of six million dollars, though the original cost of ships and forts must have been twice that, while five thousand dollars would repair the damage done to the American ships. But the property loss was the least loss to Spain, and its gain the least gain to the United States. The greatest was the Philippine and other islands, victory over Spain, imperialism and expansion, a new life and new policy for the people of the United States.

This signal victory, the greatest in some respects in ancient or modern warfare, was due primarily to the courage and efficiency of the United States navy. The gunnery was superb, the men having been thoroughly drilled in target-practice and in ship routine. Though working together as one man, like a finely constructed machine, the men were not machines only, but each one was fired by intelligence and determination. The officers were the embodiment of cool courage and high practical efficiency. The Commander-in-Chief was worthy to direct such a force, possessing a full practical knowledge of everything pertaining to his profession, with a genius for naval tactics, and consummate skill in carrying out his well-matured purpose.

Admiral Montojo was carried for safe-keeping and recuperation to a convent in the town, as the Spaniards have a way of killing or mobbing their unsuccessful commanders. A week later he wrote to General Lazaga, at Paris:

The first of May at five o’clock in the morning we saw the American squadron forming in line at a distance of three miles between Manila and Cavité. I opened fire, which soon extended all along the front of battle, the enemy directing most of his blows against my flagship. The melinite projectiles having set on fire the cruisers Cristina and Castilla, I transported myself with my staff to the Cuba. What more need I say? We beat a retreat on Bacoor, where we continued the defense until I gave the order to sink our disabled ships. They disappeared in the waves, with our glorious flag nailed to their masts. The enemy immediately took possession of the arsenal of Cavité, which surrendered after being evacuated by our soldiers, bearing their arms. Thus abandoned, Cavité was left to the horrors of pillage by the rebels in the presence of the Americans, whose indifference constituted approval. I betook myself to Manila by land, fatigued and slightly wounded in the leg, having been able to convince myself once more that the navy was neither understood nor appreciated. In the capital the fear of a bombardment caused great panic, and everybody asked himself how, with four such miserable ships, we had been able to sustain the attack of eight first-class ships, recently constructed and furnished with superior artillery. Four hundred of our marines were wounded by the fire of the enemy. Of that number one hundred eighty, of whom the half are dead, were from my flagship. Commodore Dewey has said to me through the English Consul that he would esteem it as much an honor as a pleasure if he could one day shake me by the hand to felicitate me on my conduct. This proves that one more often finds justice in an enemy, superb and noble, than among one’s own com patriots. By the mediation of the consul I have obtained leave from the Commodore for the sick and wounded in the hospital of Canacao to leave for Manila, where they will be cared for and protected from the fury of the natives.”

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Battle of Manila Bay by Hubert Howe Bancroft from his book The New Pacific published in 1900. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Battle of Manila Bay here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.