This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: The US Fleet Leaves Port.

Introduction

In the rematch between the United States and Great Britain (the War of 1812) one of the chief war goals of the United States was to conquer and acquire Canada. In short, a do-over of the failed invasion of Canada in the first war.

Since the American Revolution, the United States had grown much more powerful by 1812. The Canadian/British army would now have to defend a front of 1,400 miles from Maine to Minnesota. The strategic problem was that 900 mils of that distance was blocked by the Great Lakes. If the United States wanted to use its advantage to make the Canadian/British defenders stretch their forces, then they would have to control at least one of those lakes that bordered Canada.

This battle is significant for naval history for this reason: this was the only real fleet action the U.S. Navy fought until World War II. Other actions in this war were single ship battle. (The fleet battles of the Spanish War at the end of the century were more massacres than battles.)

Theodore Roosevelt’s spirited account of this action is not only interesting as a historical narrative and the subsequent fame of the author but is also of special value for its critical analysis and comparative estimate of an exploit that for almost a century has been regarded as one of the chief glories of the United States Navy.

This selection is from The Naval War of 1812 by Theodore Roosevelt published in 1882. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) was a historian and a President of the United States.

Time: 1813

Place: Lake Erie of the Great Lakes

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Captain Oliver Hazard Perry had assumed command of Erie and the upper lakes, acting under Commodore Chauncey. With intense energy he at once began creating a naval force which should be able to contend successfully with the foe. The latter in the beginning had exclusive control of Lake Erie; but the Americans had captured the Caledonia brig, and purchased three schooners, afterward named the Somers, Tigress, and Ohio, and a sloop, the Trippe. These at first were blockaded in the Niagara, but after the fall of Fort George and the retreat of the British forces Captain Perry was enabled to get them out, tacking them up against the current by the most arduous labor. They ran up to Presqu’île (now called Erie), where two twenty-gun brigs were being constructed under the directions of the indefatigable captain. Three other schooners, the Ariel, Scorpion, and Porcupine, were also built.

The harbor of Erie was good and spacious but had a bar on which there was less than seven feet of water. Hitherto this had prevented the enemy from getting in; now it prevented the two brigs from getting out. Captain Robert Heriot Barclay had been appointed commander of the British forces on Lake Erie; and he was having built at Amherstburg a twenty-gun ship. Meanwhile he blockaded Perry’s force, and as the brigs could not cross the bar, with their guns in, or except in smooth water, they of course could not do so in his presence. He kept a close blockade for some time but on August 2nd he disappeared. Perry at once hurried forward everything and on the 4th, at 2 P.M., one brig, the Lawrence, was towed to that point of the bar where the water was deepest. Her guns were whipped out and landed on the beach, and the brig got over the bar by a hastily improvised “camel.”

Two large scows, prepared for the purpose, were hauled alongside, and the work of lifting the brig proceeded as fast as possible. Pieces of massive timber had been run through the forward and after ports, and when the scows were sunk to the water’s edge the ends of the timbers were blocked up, supported by these floating foundations. The plugs were now put in the scows, and the water was pumped out of them. By this process the brig was lifted quite two feet, though when she was got on the bar it was found that she still drew too much water. It became necessary, in consequence, to cover up everything, sink the scows anew, and block up the timbers afresh. This duty occupied the whole night. ”

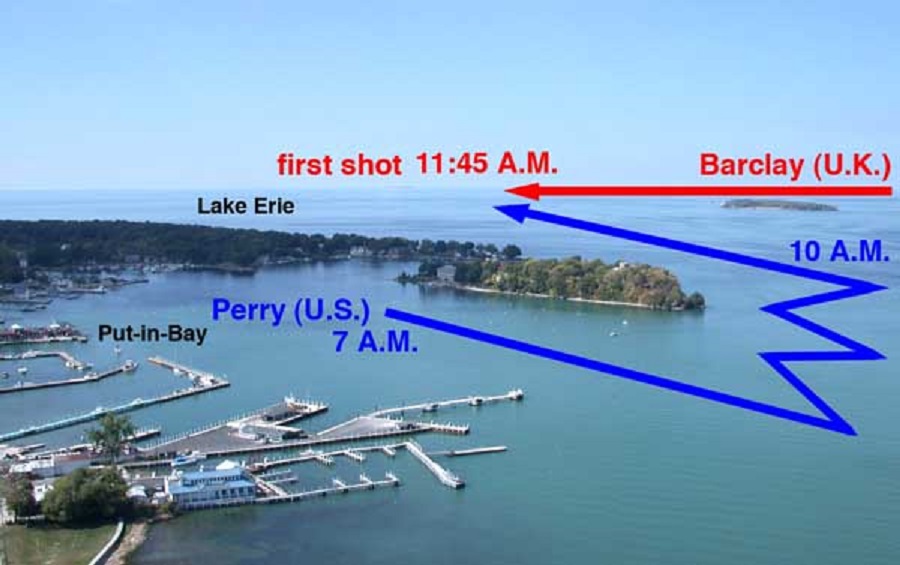

Just as the Lawrence had passed the bar, at 8 A.M. on the 5th, the enemy reappeared, but too late; Captain Barclay exchanged a few shots with the schooners and then drew off. The Niagara crossed without difficulty. There were still not enough men to man the vessels, but a draft arrived from Ontario, and many of the frontiersmen volunteered, while soldiers also were sent on board. The squadron sailed on the 18th in pursuit of the enemy, whose ship was now ready. After cruising about some time the Ohio was sent down the lake, and the other ships went into Put-in Bay. On September 9th Captain Barclay put out from Amherstburg, being so short of provisions that he felt compelled to risk an action with the superior force opposed. On September 10th his squadron was discovered from the masthead of the Lawrence in the northwest. Before going into details of the action we will examine the force of the two squadrons, as the accounts vary considerably.

The tonnage of the British ships, as already stated, we know exactly; they having been all carefully appraised and measured by the builder, Mr. Henry Eckford, and two sea captains. We also know the dimensions of the American ships. The Lawrence and Niagara measured 480 tons apiece. The Caledonia brig was about the size of the Hunter, or 180 tons. The Tigress, Somers, and Scorpion were subsequently captured by the foe, and were then said to measure respectively 96, 94, and 86 tons; in which case they were larger than similar boats on Lake Ontario. The Ariel was about the size of the Hamilton; the Porcupine and Trippe about the size of the Asp and Pert. As for the guns, Captain Barclay in his letter gives a complete account of those on board his squadron. He has also given a complete account of the American guns, which is most accurate, and, if anything, underestimates them. At least Emmons in his History gives the Trippe a long 32, while Barclay says she had only a long 24; and Lossing in his Field Book says (but I do not know on what authority) that the Caledonia had three long 24’s, while Barclay gives her two long 24’s and one 32-pound carronade; and that the Somers had two long 32’s, while Barclay gives her one long 32 and one 24-pound carronade. I shall take Barclay’s account, which corresponds with that of Emmons; the only difference being that Emmons puts a 24-pounder on the Scorpion and a 32 on the Trippe, while Barclay reverses this. I shall also follow Emmons in giving the Scorpion a 32-pound carronade instead of a 24.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.