This series has seven easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Panama Declares Independence from Columbia.

Introduction

When the United States came into possession of Hawaii and the Philippines, and it was evident that the commerce of the Pacific would soon rival that of the Atlantic, the desire for comparatively easy water communication between the Eastern States and the Pacific slope became more urgent than ever, and after another struggle between the advocates of the two routes the Panama plan prevailed and was made a Government enterprise, the story of which is told in this series.

The selections are from:

- Article in Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 20 by A. Maurice Low published in 1914.

- Speech to the US Senate by Chauncey M. Depew delivered on January 14, 1904..

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

There’s 2 installments by A. Maurice Low and 5 installments by Chauncey M. Depew.

We begin with A. Maurice Low (1860-1929). He was an English political scientist and journalist.

Time: 1903

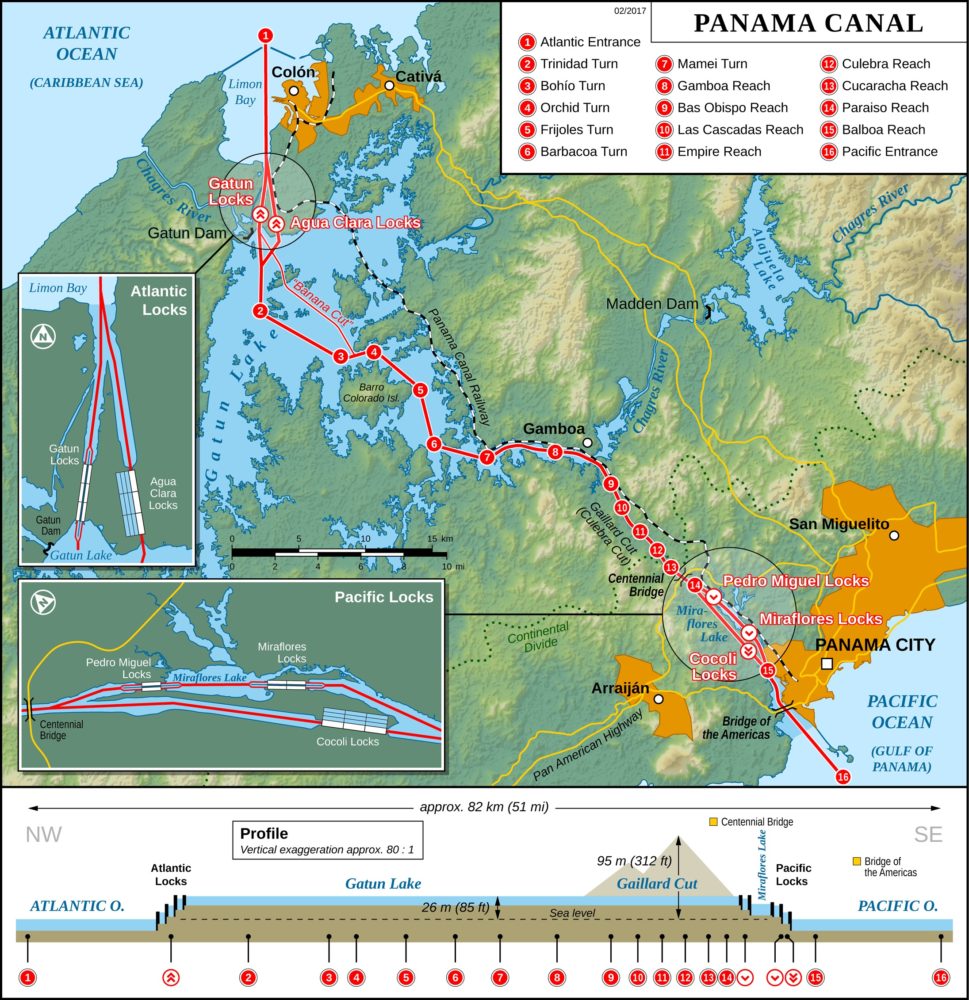

CC BY-SA 2.0 image from Wikipedia.

In 1903 the United States wrote a chapter in the world ‘ s history. Again it drove a peg into the Monroe Doctrine and reaffirmed its primacy on the American continent. Hitherto the spread of American influence has been to the west. The year 1903 saw the beginning of the sweep to the south.

In September the Colombian Congress refused to ratify the Hay-Herran Treaty negotiated in Washington, by which the United States was to be permitted to construct a canal through the Isthmus of Panama to link the Atlantic with the Pacific, subject to the payment of ten million dollars for concessionary rights and an annual rental of two hundred fifty thousand dollars. The Bogota Government had been warned that failure to ratify the treaty would be followed by a revolution in the State of Panama, which expected to profit materially by the canal. The Washington Government was also not unaware of the impending revolution. On November 3rd Panama declared its independence of Colombia, and its existence as a sovereign State under the name of the Republic of Panama. A force of Colombian troops, about five hundred in all, was at both ends of the isthmus, in the principal cities of Colon and Panama. A small American gunboat, the Nashville, was in the harbor of Colon.

The commander of the Nashville landed a detachment of marines for the ostensible purpose of protecting the property of the railway company and keeping transit open across the isthmus – a duty devolving upon the United States under the stipulations of the Treaty of 1846 with New Granada, the predecessor of Colombia. The commander of the Nashville made it known that in case the Colombian troops attacked the forces of the Provisional Government of Panama he should come to the assistance of Panama; he also announced his determination to maintain uninterrupted the railway communication across the isthmus; and, to prevent any interference with the proper running of trains, the railway could not be used for the conveyance of troops, nor would fighting be permitted along its route, or in the terminal cities of Panama and Colon. In other words, if Colombia wished to recover its lost territory, and found it necessary to use force, it might fight, but it must not fight at the only places where fighting would be of the least material advantage. These were bold words of the Nashville ‘ s commander, as at that time he could not put more than forty men on shore, the Panama Government had neither troops nor arms, and the Colombian soldiery outnumbered him ten to one. For two days the situation was critical, then heavy American reinforcements arrived on both the Atlantic and Pacific sides of the isthmus. The revolution was over. The Colombian troops sullenly permitted themselves to be deported without having fired a shot. A provisional junta was constituted to manage the affairs of the new Republic until the election of a president and the adoption of a constitution; and three days after the Re public came into being the United States gave it an international status by formally recognizing it, and entering into diplomatic relations. Other Governments promptly followed suit, but Great Britain held off until December 22d, or until Panama had agreed to assume a part of the foreign debt of Colombia proportionate to her population.

The original cause of the revolution had been the failure of Colombia to ratify the canal treaty and the desire of the people of Panama to see the canal built. The new Republic without loss of time entered into negotiations with the United States for a treaty, which was signed by Secretary Hay, for the United States, and M. Phillipe Bunau Varilla, the Panama Minister Plenipotentiary in Washington, on November 18th. By the terms of the treaty the United States agrees to safeguard the independence of the new Republic. The Republic of Panama on its part agrees to a perpetual grant of a strip of land ten miles wide, extending from ocean to ocean, together with the usual territorial sea limits of three nautical miles at both ends of the grant. This, of course, includes any and all islands within these limits. Over this territory the United States has practically unlimited control, including the right to erect fortifications, maintain garrisons and exercise all the rights of sovereignty. The money consideration for these privileges is ten million dollars to be paid the Republic of Panama on the exchange of ratifications, and an annual payment of two hundred fifty thousand dollars, beginning nine years after such ratification.

No more attention was paid to the protest of Colombia than to the bribe of a new canal treaty. So far as the independence of Panama was concerned, that was a fait accompli and could not be changed. The United States denied that it had encouraged or assisted the revolution. It claimed not only rights under the Treaty of 1846, but that certain obligations were imposed upon it, one of the highest being the duty to preserve free and uninterrupted transit over the highway between the Atlantic and the Pacific. In performance of that duty it had used its military forces to prevent interference with the railway or dislocation of business in Panama and Colon. As for the offer of Colombia to enter into negotiations for a new canal treaty, that was impossible, because the territory affected was no longer Colombian, but had passed to Panama.

The Government of Colombia threatened to compel Panama to return to her former allegiance, and began to mobilize troops, after appealing in vain to some of the European Powers for assistance. The United States met these threats by concentrating a powerful naval force in both oceans and preparing plans for sending infantry and artillery to the isthmus in case of necessity. The year closed with active military preparations proceeding on the part of the United States and some doubt existing whether Colombia would be rash enough to force a trial of strength with its powerful northern opponent.

| Master List | Next—> |

Chauncey M. Depew begins here.

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.