This series has two easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Old Man With Vigor and Grievance.

Introduction

Marino Falieri was born at Venice about 1278, and was elected doge in 1354. For many years the government of the republic, under an oligarchy, had been arbitrarily dominated by the Council of Ten, an assembly that, after serving a special purpose for which it was created, was declared permanent in 1325 and became a formidable tribunal. Professing to guard the republic the Ten in fact destroyed its liberties, disposed of its finances, overruled the constitutional legislators, suppressed and excluded the popular element from all voice in public affairs, and finally reduced the nominal prince — the doge — to a mere puppet or an ornamental functionary, still called “head of the state.”

At the time when Falieri entered upon his dogeship the city in all quarters was pervaded by the spies of this great oligarchy, which seized and imprisoned citizens, and even put them to death, secretly, without itself being answerable to any authority. The most notable event in the annals of this extraordinary Venetian government is that which forms the story of Marino Falieri himself. His conspiracy with the plebeians to assassinate the oligarchs and make himself actual ruler of the state had the double motive of a personal grievance and the sense of a political wrong.

The fate of this old man has been made the subject of tragedies by Byron (1820), Casimir Delavigne (1829), and Swinburne (1885). The novel, Doge und Dogaressa, by Ernst Theodor Hoffmann, was inspired by the same dramatic figure. Of historical accounts, the following — in Ms. Oliphant’s best manner — is justly regarded as the most impressive which has hitherto appeared in English.

This selection is from The Makers of Venice by Margaret Oliphant published in 1887. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Margaret Oliphant (1828-1897) was a Scottish writer of history and fiction.

Time: 1365

Place: Venice

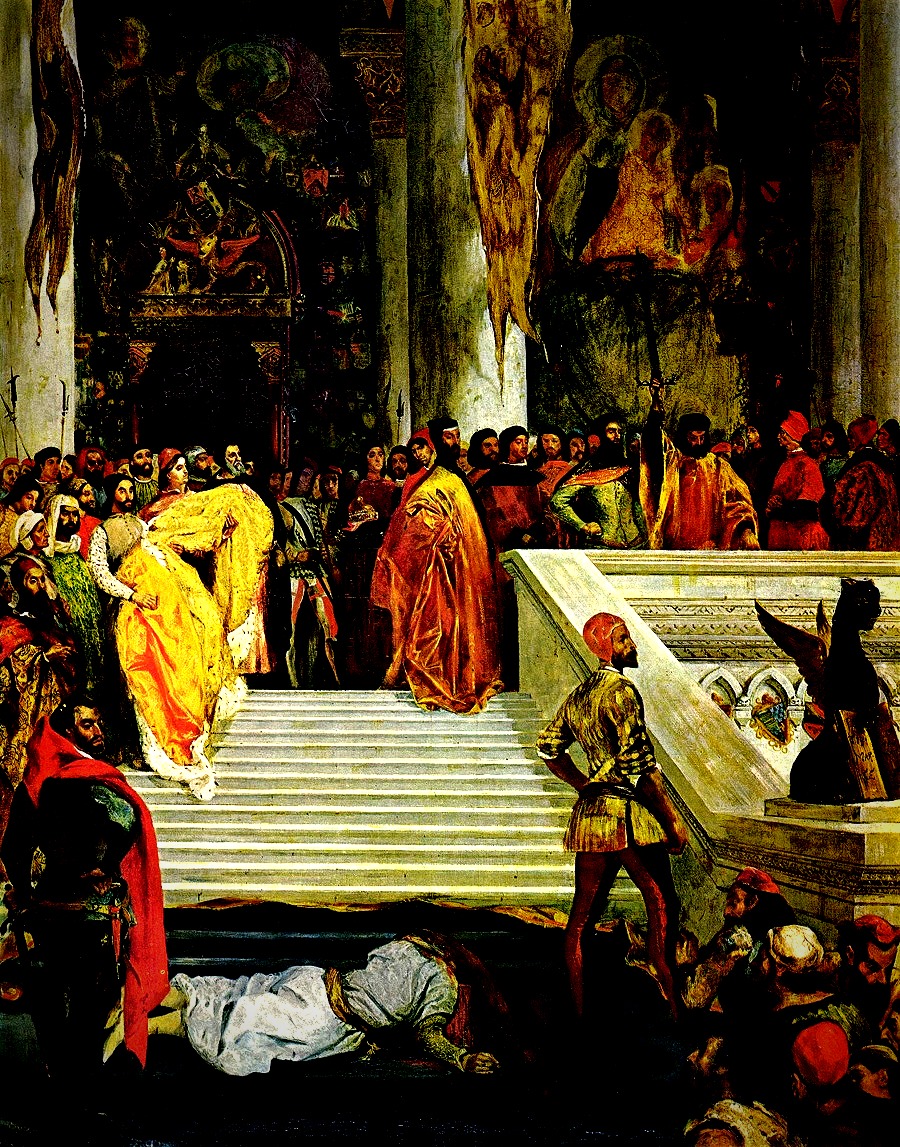

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Marino Falieri had been an active servant of Venice through a long life. He had filled almost all the great offices which were entrusted to her nobles. He had governed her distant colonies, accompanied her armies in that position of proveditore, omnipotent civilian critic of all the movements of war, which so much disgusted the generals of the republic. He had been ambassador at the courts of both emperor and pope, and was serving his country in that capacity at Avignon when the news of his election reached him.

It is thus evident that Falieri was not a man used to the position of a lay figure, although at seventy-six the dignified retirement of a throne, even when so encircled with restrictions, would seem not inappropriate. That he was of a haughty and hasty temper seems apparent. It is told of him that, after waiting long for a bishop to head a procession at Treviso where he was podesta (“chief magistrate”), he astonished the tardy prelate by a box on the ear when he finally appeared, a punishment for keeping the authorities waiting.

Old age to a statesman, however, is in many cases an advantage rather than a defect, and Falieri was young in vigor and character, and still full of life and strength. He was married a second time to presumably a beautiful wife much younger than himself, though the chroniclers are not agreed even on the subject of her name, whether she was a Gradenigo or a Contarini. The well-known story of young Steno’s insult to this lady and to her old husband has found a place in all subsequent histories, but there is no trace of it in the unpublished documents of the state.

The story goes that Michel Steno, one of those young and insubordinate gallants who are a danger to every aristocratic state, having been turned out of the presence of the Dogaressa for some unseemly freedom of behavior, wrote upon the chair of the Doge in boyish petulance an insulting taunt, such as might well rouse a high-tempered old man to fury. According to Sanudo, the young man, on being brought before the Forty, confessed that he had thus avenged himself in a fit of passion; and regard having been had to his age and the “heat of love” which had been the cause of his original misdemeanor — a reason seldom taken into account by the tribunals of the state — he was condemned to prison for two months, and afterward to be banished for a year from Venice.

The Doge took this light punishment greatly amiss, considering it, indeed, as a further insult.

Sabellico says not a word of Michel Steno, or of this definite cause of offence, and Romanin quotes the contemporary records to show that though Alcuni zovanelli fioli de gentiluomini di Venetia are supposed to have affronted the Doge, no such story finds a place in any of them. But the old man thus translated from active life and power, soon became bitterly sensible in his new position that he was senza parentado, with few relations, and flouted by the giovinastri, the dissolute young gentlemen who swaggered about the Broglio in their finery, strong in the support of fathers and uncles.

That he found himself, at the same time, shelved in his new rank, powerless, and regarded as a nobody in the state where hitherto he had been a potent signior — mastered in every action by the secret tribunal, and presiding nominally in councils where his opinion was of little consequence — is evident. And a man so well acquainted, and so long, with all the proceedings of the state, who had seen consummated the shutting out of the people, and since had watched through election after election a gradual tightening of the bonds round the feet of the doge, would naturally have many thoughts when he found himself the wearer of that restricted and diminished crown.

He could not be unconscious of how the stream was going, nor unaware of that gradual sapping of privilege and decreasing of power which even in his own case had gone further than with his predecessor. Perhaps he had noted with an indignant mind the new limits of the promissione, a narrower charter than ever, when he was called upon to sign it. He had no mind, we may well believe, to retire thus from the administration of affairs. And when these giovinastri, other people’s boys, the scum of the gay world, flung their unsavory jests in the face of the old man who had no son to come after him, the silly insults so lightly uttered, so little thought of, the natural scoff of youth at old age, stung him to the quick.

Old Falieri’s heart burned within him at his own injuries and those of his old comrades. How he was induced to head the conspiracy, and put his crown, his life, and honor on the cast, there is no further information. His fierce temper, and the fact that he had no powerful house behind him to help to support his case, probably made him reckless. In April, 1355, six months after his arrival in Venice as doge, the smoldering fire broke out. Two of the conspirators were seized with compunction on the eve of the catastrophe and betrayed the plot — one with a merciful motive to serve a patrician he loved, the other with perhaps less noble intentions — and, without a blow struck, the conspiracy collapsed. There was no real heart in it, nothing to give it consistence; the hot passion of a few men insulted, the variable gaseous excitement of wronged commoners, and the ambition — if it was ambition — of one enraged and affronted old man, without an heir to follow him or anything that could make it worth his while to conquer.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.