He described the object of the school in these words:”To make children reflect upon the lies of religion, of government, of patriotism, of justice, of politics, and of militarism; and to prepare their minds for the social revolution.”

Continuing Spanish Civil War Prelude,

our selection from Trial of Ferrer by Perceval Gibbon published in . The selection is presented in 3 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Spanish Civil War Prelude.

Time: 1909

Place: Barcelona

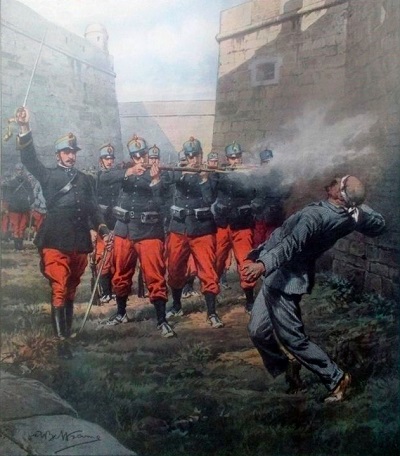

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

He opened his campaign by founding in Barcelona his Escuela Moderna, the only secular school in Spain. Here a child received sound teaching in conventional subjects, and was also trained along the peculiar lines of Ferrer’s beliefs. He described the object of the school in these words:

To make children reflect upon the lies of religion, of government, of patriotism, of justice, of politics, and of militarism; and to prepare their minds for the social revolution.”

Apart from this latter purpose, the school served a great national need, and its success was immediate. Branches were established in other parts of Spain, and it has already, in something less than eight years, turned out about four thousand pupils, well equipped to hold their own in illiterate and ignorant Spain. Also, it carried out its founder’s intention that it should be a blow at clericalism, and its power was fully recognized by the Government when, in 1906, an opportunity arose to attack Ferrer.

Among the men whom Ferrer had appointed to assist in the conduct of the Escuela Moderna was Mateo Morales, an accomplished linguist, who was given the post of librarian. He, too, was an anarchist, but not of the philosophical and theoretical kind to which Ferrer belonged. He was the man who threw the bomb at King Alfonso and his bride on the day of their wedding.

On June 4, 1906, Ferrer was arrested for complicity in this outrage, apparently for no other reason than that he had known Morales well. Not a shred of evidence could be adduced against him; there was not even enough to bring him to trial. In fact, the case was so utterly feeble that the Judge of First Instance agreed to liberate him on bail, adding that no cause had been shown why Ferrer should be either tried or detained in prison. But Ferrer was not liberated. The Fiscal intervened to prevent it — his authority was higher than that of the Judge.

“You will not be allowed bail,” he told Ferrer, “even if the Judge has permitted it, because I will stop it.”

So Ferrer went back to jail, and remained there without trial for a full year. At the end of that time a trial was arranged. Ordinarily he should have been brought before the Court of Assize, but there were reasons why the normal course of justice should not be pursued, and therefore a special court was established to try him, without a jury. No means were neglected to secure the judicial murder of the only rich man among the anticlericals, and yet the attempt failed. Evidence was offered on two points. It was shown, in the first place, that anarchists had paid visits to Ferrer. This was not denied. In the second place, there was an attempt to demonstrate that, since Morales was a poor man and Ferrer a rich one, therefore Ferrer must have supplied Morales with money to hire rooms in Madrid and make the attempt on the King’s life.

Ferrer’s counsel wished to call M. Henri Rochefort on his behalf, — he would have been a powerful witness for the defense, — but the court answered this with a refusal to hear foreign witnesses. This, however, could not silence Rochefort in the newspapers, and he published a letter from Morales to a Russian revolutionary, in which he said:

I have no faith in Ferrer, Tarrida, and Lorenzo, and all the simple-minded folk who think you can do anything with speeches.”

The case was absurd from beginning to end. Even a specially constituted court found itself unable to convict on such evidence, and Ferrer was acquitted.

This first trial took place three years ago, and ever after Ferrer was a marked man. He knew his danger and walked carefully. He conducted the increasing work of his schools, attended a Labor Federation in Paris, and visited London. When, in 1909, Barcelona flamed into open revolt, he was nowhere to be found. It is not quite clear why he should have been looked for in connection with the disorders. Violence, dynamite, and barricades are as native to Barcelona as steel to Pittsburg. In twenty-five years, to go no further back, there have been recorded in the city one hundred and fourteen bomb outrages alone, and these figures are incomplete. In the last year fifteen bombs were exploded, and in the last five months there have been eighteen more. Barcelona is forever on the brink of an outrage or an uprising; it does not need a Ferrer to stir it to its peculiar activities. But the police had orders from Madrid to lay hands on Ferrer, and he promptly went into hiding. The city was under martial law, and it was no time for Ferrer, of all people, to risk a trial.

The police effected his capture without much difficulty. He was recognized at Alella, his birthplace, arrested, and conveyed in a cart to Barcelona on September 1st. Senor Ugarte, the Public Prosecutor, announced forthwith that he considered Ferrer to have been the leading spirit in the outrages of July.

Then began Ferrer’s second trial, the wretched farce that roused the lawyers of Paris to protest against the procedure. A preliminary examination was held by a Judge of First Instance — one, that is to say, who has power only to examine, and cannot decide or sentence.

Everything was carried out according to arrangement. Ferrer was committed to take his trial before a court martial, and Captain Galceran, of the Regiment of Engineers, one of the corps d’ ‘elite of the Spanish Army, was appointed counsel for the defense. This is a post of no ordinary difficulty, for in such a case the officer must reconcile his duty to his client with a convention as to the lengths an officer of the army may go in defending a man accused of a military crime; and it has often happened that an officer acting as counsel has subsequently been punished for his overenthusiastic advocacy.

In this case Captain Galceran seems to have acted fearlessly and conscientiously. Against Ferrer there appeared seventy witnesses, not half of whose number had anything to say that could be held to aid toward a conviction. They swore blithely that they considered Senor Ferrer to be implicated; that their opinion was the general one; that he was a man whose principles made such matters natural to him. This, in fact, was the evidence of several, and others had testimony of equal relevance.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

William Archer began here. Perceval Gibbon began here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.