This is the second half of Venice Doge’s Coup

our selection from The Makers of Venice by Margaret Oliphant published in 1887.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Venice Doge’s Coup.

Time: 1365

Place: Venice

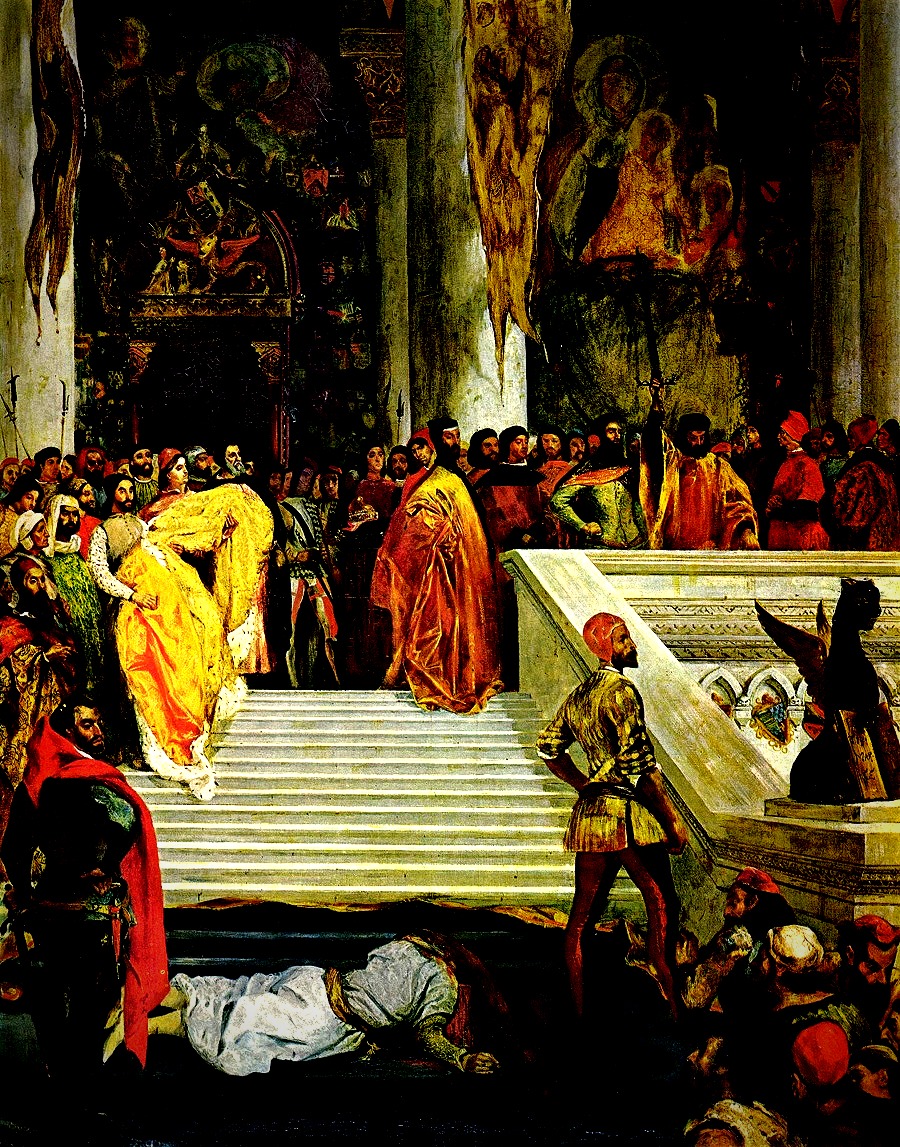

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

An enterprise more wild was never undertaken. It was the passionate stand of despair against force so overwhelming as to make mad the helpless, yet not submissive, victims. The Doge, who no doubt in former days had felt it to be a mere affair of the populace, a thing with which a noble ambassador and proveditore had nothing to do, a struggle beneath his notice, found himself at last, with fury and amazement, to be a fellow-sufferer caught in the same toils. There seems no reason to believe that Falieri consciously staked the remnant of his life on the forlorn hope of overcoming that awful and pitiless power, with any real hope of establishing his own supremacy. His aspect is rather that of a man betrayed by passion, and wildly forgetful of all possibility in his fierce attempt to free himself and get the upper hand. One cannot but feel in that passion of helpless age and unfriendedness, something of the terrible disappointment of one to whom the real situation of affairs had never been revealed before; who had come home triumphant to reign like the doges of old, and, only after the ducal cap was on his head and the palace of the state had become his home, found out that the doge — like the unconsidered plebeian — had been reduced to bondage; his judgment and experience put aside in favor of the deliberations of a secret tribunal, and the very boys, when they were nobles, at liberty to jeer at his declining years.

The lesser conspirators, all men of the humbler sort — Calendario, the architect, who was then at work upon the palace, a number of seamen, and other little-known persons — were hanged; not like the greater criminals, beheaded between the columns, but strung up — a horrible fringe — along the side of the palazzo. The fate of Falieri himself is too generally known to demand description. Calmed by the tragic touch of fate, the Doge bore all the humiliations of his doom with dignity, and was beheaded at the head of the stairs where he had sworn the promissione on first assuming the office of doge.

What a contrast was this from that triumphant day when probably he felt that his reward had come to him after the long and faithful service of years. Death stills disappointment as well as rage, and Falieri is said to have acknowledged the justice of his sentence. He had never made any attempt to justify or defend himself, but frankly and at once avowed his guilt and made no attempt to escape from its penalties. His body was conveyed privately to the Church of St. Giovanni and St. Paolo, the great “Zanipolo” — with which all visitors to Venice are familiar — and was buried in secrecy and silence in the atrio of a little chapel behind the great church — where no doubt for centuries the pavement was worn by many feet with little thought of those who lay below. Even from that refuge his bones have been driven forth, but his name remains in the corner of the Hall of the Great Council, where — with a certain dramatic affectation — the painter-historians have painted a black veil across the vacant place. “This is the place of Marino Falieri, beheaded for his crimes,” is all the record left of the Doge disgraced.

Was it a crime? The question is one which it is difficult to discuss with any certainty. That Falieri desired to establish — as so many had done in other cities — an independent despotism in Venice, seems entirely unproved. It was the prevailing fear; the one suggestion which alarmed everybody and made sentiment unanimous. But one of the special points which are recorded by the chroniclers as working in him to madness, was that he was senza parentado — without any backing of relationship or allies — i.e., sonless, with no one to come after him. How little likely then was an old man to embark on such a desperate venture for self-aggrandizement merely. He had, indeed, a nephew who was involved in his fate, but apparently not so deeply as to expose him to the last penalty of the law.

The incident altogether points more to a sudden outbreak of the rage and disappointment of an old public servant coming back from his weary labors for the state in triumph and satisfaction to what seemed the supreme reward; and finding himself no more than a puppet in the hands of remorseless masters, subject to the scoffs of the younger generation, with his eyes opened by his own suffering, perceiving for the first time what justice there was in the oft-repeated protest of the people, and how they and he alike were crushed under the iron heel of that oligarchy to which the power of the people and that of the Prince were equally obnoxious. The chroniclers of his time were so much at a loss to find any reason for such an attempt on the part of a man, non abbiando alcum propinquo, that they agree in attributing it to diabolical inspiration.

It was more probably that fury which springs from a sense of wrong, which the sight of the wrongs of others raised to frenzy, and that intolerable impatience of the impotent which is more harsh in its hopelessness than the greatest hardihood. He could not but die for it, but there seems no more reason to characterize this impossible attempt as deliberate treason than to give the same name to many an alliance formed between prince and people in other regions — the king and commons of the early Stuarts, for example — against the intolerable exactions and cruelty of an aristocracy too powerful to be faced alone by either.

| <—Previous | Master List |

More information on Venice Doge’s Coup here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.