Today’s installment concludes First Carlist Revolt,

our selection from History of Modern Europe by Charles A. Fyffe published in 1890.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in First Carlist Revolt.

Time: 1833

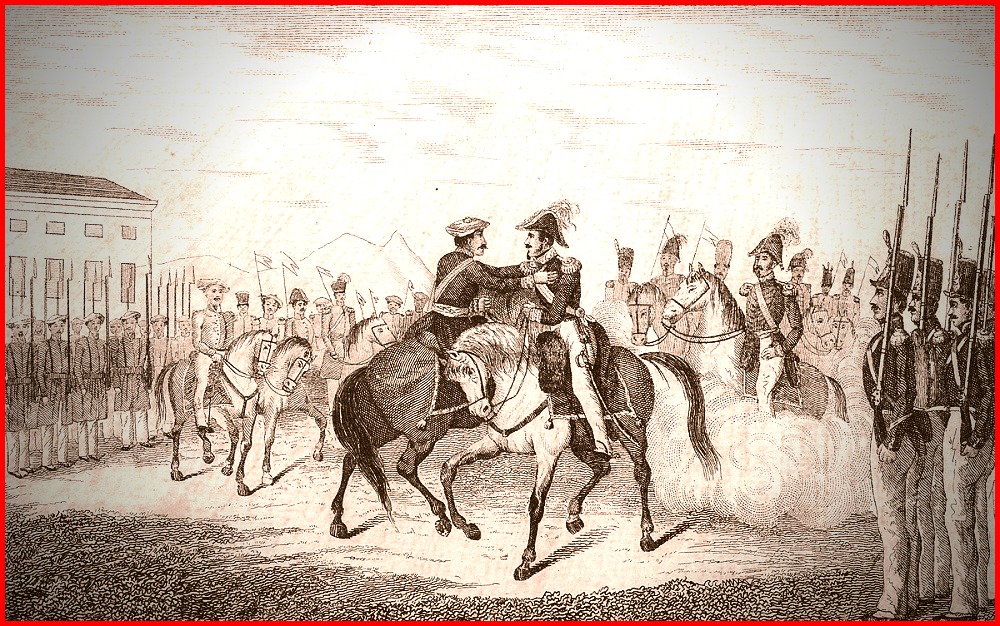

CC BY-SA 4.0 image from Wikipedia.

On the other hand, the experience gained from earlier military enterprises in Spain might well deter even bolder politicians than those about Louis Philippe from venturing upon a task whose ultimate issues no man could confidently forecast. Napoleon had wrecked his empire in the struggle beyond the Pyrenees not less than in the march to Moscow: and the expedition of 1823, though free from military difficulties, had exposed France to the humiliating responsibility for every brutal act of a despotism which, in the very moment of its restoration, had scorned the advice of its restorers. The constitutional Government which invoked French assistance might, moreover, at any moment give place to a democratic faction which already harassed it within the Cortes, and which, in its alliance with the populace in many of the great cities, threatened to throw Spain into anarchy, or to restore the ill-omened Constitution of 1812.

But above all, the attitude of the three Eastern powers bade the ruler of France hesitate before committing himself to a military occupation of Spanish territory. Their sympathies were with Don Carlos, and the active participation of France in the quarrel might possibly call their opposing forces into the field and provoke a general war. In view of the evident dangers arising out of the proposed intervention, the French Government, taking its stand on that clause of the Quadruple Treaty which provided that the assistance of France should be rendered in such manner as might be agreed upon by all the parties to the treaty, addressed itself to Great Britain, inquiring whether this country would undertake a joint responsibility in the enterprise and share with France the consequences to which it might give birth. Lord Palmerston in reply declined to give the assurance required. He stated that no objection would be raised by the British Government to the entry of French troops into Spain, but that such intervention must be regarded as the work of France alone, and be undertaken by France at its own peril.

This answer sufficed for Louis Philippe and his ministers. The Spanish Government was informed that the grant of military assistance was impossible, and that the entire public opinion of France would condemn so dangerous an undertaking. As a proof of goodwill, permission was given to Queen Christina to enroll volunteers both in England and France. Arms were supplied; and some thousands of needy or adventurous men ultimately made their way from England as well as from France, to earn under Colonel De Lacy Evans and other leaders a scanty harvest of profit or renown.

The first result of the rejection of the Spanish demand for the direct intervention of France was the downfall of the minister (Valdes) by whom this demand had been made. His successor, Toreno, though a well-known patriot, proved unable to stem the tide of revolution that was breaking over the country. City after city set up its own Junta, and acted as if the central Government had ceased to exist. Again the appeal for help was made to Louis Philippe, and now not so much to avert the victory of Don Carlos as to save Spain from anarchy and from the Constitution of 1812. Before an answer could arrive, Toreno in his turn had passed away.

Mendizabal, a banker who had been entrusted with financial business at London, and who had entered into friendly relations with Lord Palmerston, was called to office, as a politician accept able to the democratic party, and the advocate of a close connection with England rather than with France. In spite of the confident professions of this minister, and in spite of some assistance actually rendered by the English fleet, no real progress was made in subduing the Carlists or in restoring administrative and financial order. The death of Zumalacarregui, who was forced by Don Carlos to turn northward and besiege Bilbao instead of marching upon Madrid immediately after his victories, had checked the progress of the rebellion at a critical moment; but the Government, distracted and bankrupt, could not use the opportunity which thus offered itself, and the war soon blazed out anew, not only in the Basque Provinces but throughout the North of Spain. For year after year the monotonous struggle continued, while Cortes succeeded Cortes and faction supplanted faction until there remained scarcely an officer who had not lost his reputation or a politician who was not useless and discredited.

The Queen Regent, who from the necessities of her situation had for a while been the representative of the popular cause, gradually identified herself with the interests opposed to democratic change; and although her name was still treated with some respect and her policy was habitually attributed to the misleading advice of courtiers, her real position was well understood at Madrid, and her own resistance was known to be the principal obstacle to the restoration of the Constitution of 1812. It was therefore determined to overcome this resistance by force; and on August 13, 1836, a regiment of the garrison of Madrid, won over by the Exaltados, marched upon the palace of La Granja, invaded the Queen’s apartments, and compelled her to sign an edict restoring the Constitution of 1812 until the Cortes should establish that or some other.

Scenes of riot and murder followed in the capital. Men of moderate opinions, alarmed at the approach of anarchy, prepared to unite with Don Carlos. King Louis Philippe, who had just consented to strengthen the French legion by the addition of some thousands of trained soldiers, now broke entirely from the Spanish connection, and dismissed his ministers who refused to acquiesce in this change of policy. Meanwhile the Eastern powers and all rational partisans of absolutism besought Don Carlos to give those assurances which would satisfy the wavering mass among his opponents, and place him on the throne without the sacrifice of any right that was worth preserving. It seemed as if the opportunity was too clear to be misunderstood; but the obstinacy and narrowness of Don Carlos were proof against every call of fortune. Refusing to enter into any sort of engagement, he rendered it impossible for men to submit to him who were not willing to accept absolutism pure and simple.

On the other hand, a majority of the Cortes, whose eyes were now opened to the dangers around them, accepted such modifications of the Constitution of 1812 that political stability again appeared possible (June, 1837). The danger of a general transference of all moderate elements in the State to the side of Don Carlos was averted; and, although the Carlist armies took up the offensive, menaced the capital, and made incursions into every part of Spain, the darkest period of the war was now over; and when Don Carlos fell back in confusion to the Ebro, the suppression of the rebellion became a certainty.

General Espartero forced back the adversary step by step, and carried fire and sword into the Basque Provinces, employing a system of devastation for exhausting the endurance of the people. Reduced to the last extremity, the Carlist leaders turned their arms against one another.

Finally, on September 14, 1839, after the surrender of almost all his troops to Espartero, Don Carlos crossed the French frontier, and the conflict was at an end.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on First Carlist Revolt by Charles A. Fyffe from his book History of Modern Europe published in 1890. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on First Carlist Revolt here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.