This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Don Carlos Asserts His Claim to the Spanish Throne.

Introduction

This uprising was more than the attempt of the pretender Don Carlos to seat himself upon the Spanish throne. It was one of many struggles in Europe that received the support of the same influences that, through the Holy Alliance, had sought to repress the growth of constitutional liberty. The revolt also marks the rise of a Spanish party, the Carlists, who have continued, with fresh risings from time to time, to serve the cause of Don Carlos and several subsequent claimants under his assumed title. The public support for the dynastic claims of Don Carlos were based on his opposition to liberalism and especially to the Spanish liberals’ opposition to the Catholic Church.

In the end Franco absorbed the Carlists into his Nationalist Movement during the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s – a full century after the events narrated below.

This selection is from History of Modern Europe by Charles A. Fyffe published in 1890. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Charles A. Fyffe (1845-1892) was an English historian, journalist, and politician for the Liberal Party.

Time: 1833

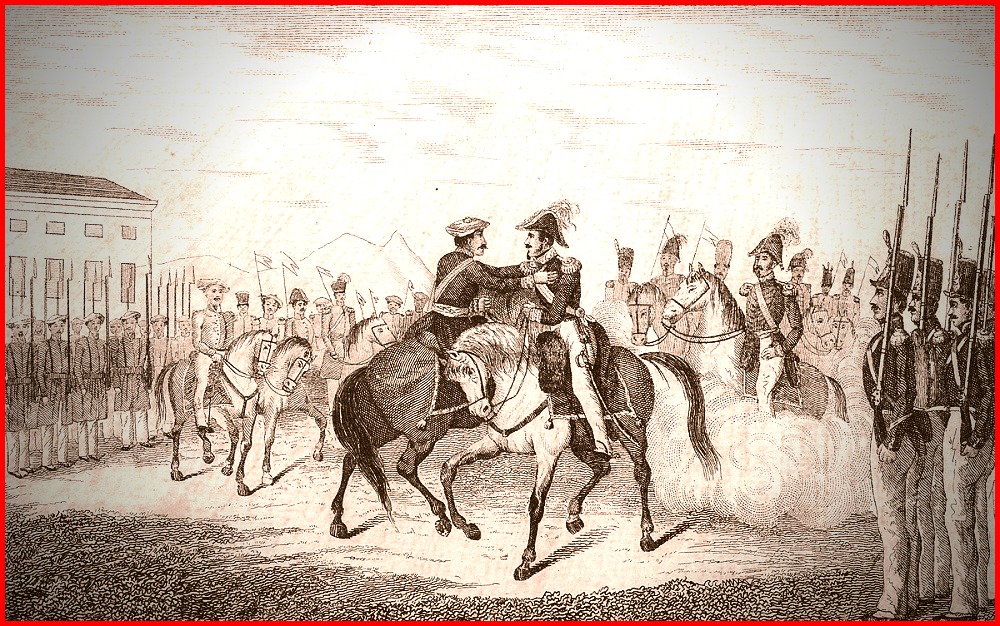

CC BY-SA 4.0 image from Wikipedia.

From the time of the restoration of absolute government in Spain in 1823, King Ferdinand, from his abject weakness and ignorance, had not given complete satisfaction to the people. He had been thrice married; he was childless, his state of health miserable, and his life likely to be short. The succession to the throne of Spain had, moreover, since 1713, been governed by the Salic Law, so that even in the event of Ferdinand leaving female issue Don Carlos would nevertheless inherit the crown. These confident hopes were rudely disturbed by the marriage of the King with his cousin, Maria Christina of Naples, followed by an edict, known as the Pragmatic Sanction, repealing the Salic Law which had been introduced with the first Bourbon, and restoring the ancient Castilian custom under which women were capable of succeeding to the crown. A daughter, Isabella, was shortly afterward born to the new Queen.

On the legality of the Pragmatic Sanction the opinions of publicists differed; it was judged, however, by Europe at large not from the point of view of antiquarian theory, but with direct reference to its immediate effect. The three Eastern courts emphatically condemned it, as an interference with established monarchical right, and as a blow to the cause of European absolutism through the alliance which it would almost certainly produce between the supplanters of Don Carlos and the Liberals of the Spanish Peninsula. To the clerical and reactionary party at Madrid, it amounted to nothing less than a sentence of destruction, and the utmost pressure was brought to bear upon the weak and dying King with the object of inducing him to undo the alleged wrong which he had done to his brother.

In a moment of prostration Ferdinand revoked the Pragmatic Sanction; but subsequently, regaining some degree of strength, he reenacted it, and appointed Christina regent during the continuance of his illness. Don Carlos, protesting against the violation of his rights, had betaken himself to Portugal, where he made common cause with Miguel. * His adherents had no intention of submitting to the change of succession. Their resentment was scarcely restrained during Ferdinand’s lifetime, and when, in September, 1833, his long-expected death took place, and the child Isabella was declared queen under the regency of her mother, open rebellion broke out, and Carlos was proclaimed king in several of the Northern Provinces.

[* Dom Miguel, third son of John VI of Portugal, was head of the Absolutist party in that country, whose throne he usurped in 1828. — Ed.]

For the moment the forces of the Regency seemed to be far superior to those of the insurgents, and Don Carlos failed to take advantage of the first outburst of enthusiasm and to place himself at the head of his followers. He remained in Portugal, while Christina, as had been expected, drew nearer to the Spanish Liberals, and ultimately called to power a Liberal minister, Martinez de la Rosa, under whom a constitution was given to Spain by a royal statute (April 10, 1834). At the same time negotiations were opened with Portugal and with the Western powers, in the hope of forming an alliance which should drive both Miguel and Carlos from the Peninsula.

On April 22, 1834, a quadruple treaty was signed at London, in which the Spanish Government undertook to send an army into Portugal against Miguel, the Court of Lisbon pledging itself in return to use all the means in its power to expel Don Carlos from Portuguese territory. England engaged to cooperate by means of its fleet. The assistance of France, if it should be deemed necessary for the attainment of the objects of the treaty, was to be rendered in such manner as should be settled by common consent. In pursuance of the policy of the treaty, and even before the formal engagement was signed, a Spanish division under General Rodil crossed the frontier and marched against Miguel. The forces of the usurper were defeated. The appearance of the English fleet and the publication of the Treaty of Quadruple Alliance rendered further resistance hopeless, and on May 22d Miguel made his submission, and, in return for a large pension, renounced all rights to the crown, and undertook to quit the Peninsula forever. Don Carlos, refusing similar conditions, went on board an English ship and was conducted to London.

With respect to Portugal, the Quadruple Alliance had completely attained its object; and in so far as the Carlist cause was strengthened by the continuance of civil war in the neighboring country, this source of strength was no doubt withdrawn from it. But in its effect upon Don Carlos himself the action of the Quadruple Alliance was worse than useless. While fulfilling the letter of the treaty, which stipulated for the expulsion of the two pre tenders from the Peninsula, the English Admiral had removed Carlos from Portugal, where he was comparatively harmless, and had taken no effective guarantee that he should not reappear in Spain itself and enforce his claim by arms. Carlos had not been made a prisoner of war; he had made no promises and incurred no obligations; nor could the British Government, after his arrival in that country, keep him in perpetual restraint. Quitting England after a short residence, he travelled in disguise through France, crossed the Pyrenees, and appeared on July 10, 1834, at the headquarters of the Carlist insurgents in Navarre.

In the country immediately below the western Pyrenees, the so-called Basque Provinces, lay the chief strength of the Carlist rebellion. These Provinces, which were among the most thriving and industrious parts of Spain, might seem by their very superiority an unlikely home for a movement which was directed against everything favorable to liberty, tolerance, and progress in the Spanish Kingdom. But the identification of the Basques with the Carlist cause was due in fact to local, not to general, causes; and in fighting to impose a bigoted despot upon the Spanish people, they were in truth fighting to protect themselves from a closer incorporation with Spain. Down to the year 1812 the Basque Provinces had preserved more than half of the essentials of independence.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.