This enabled us to see the first battle of Valestinos, which, though on a small scale, was one of the most desperate and bloody engagements of the war.

Continuing Greco-Turkish War of 1897,

our selection from Battlefields of Thessaly by Sir Ellis Ashmead Bartlett published in 1897. The selection is presented in seven easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Greco-Turkish War of 1897.

Time: 1897

Place: Thessaly and Crete

CC 0 image from Wikipedia.

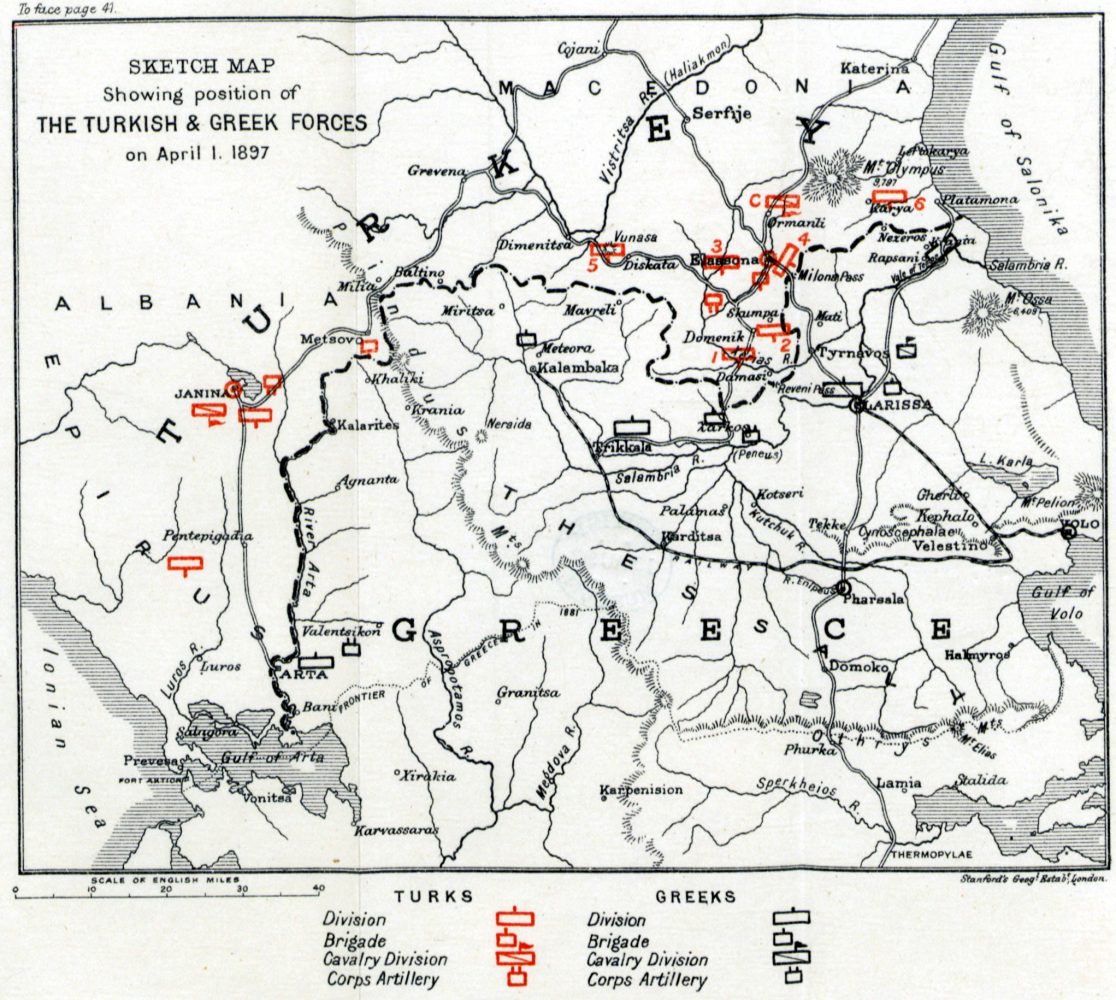

The great mountain range that forms the frontier trends sharply southward from Melouna for about fifteen miles, and Tournavos lies in the level ground just beyond the southeastern base of this huge mountainous projection. The moment, therefore, that Hairi Pacha was in a situation to debouch from the Reveni Pass into the plain, the whole position of the Greek main body, which extended about ten miles north of Tournavos, from Mati to Deliler, was in jeopardy, and retreat became a necessity. At first Hairi appeared to hold his own with some difficulty against the vigorous onslaught of Colonel Smolenski. Smolensk’s success, however, was soon made nugatory by other failures, and by the 23d his corps had to retire through the Reveni Pass upon Larissa. Neschat Pacha at Skumpa, with the Second division, was engaged in clearing away the Greeks from the block houses and ridges between Damasi and Melouna. This he accomplished by the 21st. Only one Greek position remained intact, and that was the lofty and almost impregnable summit of Kritiri, overlooking Tournavos. Between the 17th and the 23rd several assaults were made upon this tremendous natural for tress, but without success.

A continuous and heavy fire was kept up against Kritiri on the 20th and 21st, but without effect. The slopes were steep and strongly entrenched, and the Turks lost more than two hundred men in these attempts.

At the opening of the campaign the Greeks had their army of Thessaly divided into two corps, numbering more than sixty thou sand men, with their headquarters at Larissa and Trikkala. These were commanded respectively by Generals Macrise and Mavromichalis. Although their numbers were less than those of the Turks, the Greeks were in the inner line, and their means of communication were far better. They enjoyed the invaluable advantage of a railway, which ran from the sea-base at Volo to Larissa and Trikkala. The Greek officers were, by general agreement, very inferior, and the Greek general staff appeared devoid of plans either for offence or defense.

Smolenski, with seven weak battalions, is said to have held the pass at Reveni for a week against a whole Turkish division. He did not retire until after the panic flight of his compatriots from Tournavos, on April 23rd.

A curious story is told of a mistaken order for retreat, given by the Crown Prince at midday on April 19th. It seems incredible, but Greek officers did such extraordinary things, especially the headquarters staff, that it may have happened. The order is said to have been cancelled within three hours, and a counter- order given to advance again. Meanwhile, however, the hill of Gritsovali had been abandoned, and the attempt to retake it from the Turks the next day is said to have cost General Mavromichalis two thousand men. This surely must be an exaggeration. It is clear, too, that the narrative confuses the village of Dereli, near Baba, at the entrance to the Vale of Tempe, with Deliler, about three miles east of Mati, and nine miles northeast of Tournavos. It was the capture of Deliler by Hamdi’s troops on the evening of the 23rd that turned the Greek right flank and rendered the retreat to Larissa inevitable. The retreat should not have degenerated into a panic flight, but retreat was necessary to save the Greek army.

By great good fortune I decided, on April 29, to ride down the railway line toward Valestinos early the next morning. This enabled us to see the first battle of Valestinos, which, though on a small scale, was one of the most desperate and bloody engagements of the war. It was not intended by the Commander-in- Chief to be a battle at all, but merely a reconnaissance in force. Owing, however, to the impetuous foolhardiness of Mahmoud Bey, and partly owing to the obstinacy of Hakki Pacha, commander of the Third division, and of Naim Pacha, the brigadier in actual command, the reconnaissance soon developed into a formidable attack of all arms. It was pushed home with the utmost courage and tenacity, and it ended in a sanguinary re pulse. The Turks had one brigade of infantry and the cavalry division of about one thousand sabers engaged. The first reinforcements, dispatched in the small hours from a point near Larissa, did not reach Gherli until about 8 a.m. on Saturday; and it was past midday before the whole fresh division was encamped in and around that village.

It is twenty-one miles from Larissa to Gherli, and eight miles from Gherli to Valestinos by Rizomylou. The Greeks occupied a very strong position, entrenched along the low ridge of hills that lies between the precipitous heights of Pelion (Pilaf Tepe”) on their right, and Cynoscephalae on their left. The shoulder of Pelion is exceedingly steep and rocky and rises two thousand feet above the plain. The hills run northeastward from Cynosceph alae in a series of ridges that are lower toward the center. From these ridges smaller slopes run transversely, that is, northward, into the plain. The Greeks had entrenchments along several of these transverse ridges as well as along the central line. In the depression between two of them, and two miles northwest of Valestinos, lay the village of Kephalo, which the Turks captured on the 29th and held tenaciously until the evening of the 30th. There was a small round hill near the center of the Greek position, on which they had entrenchments and a very active battery. The railway line from Larissa to Volo runs through Valestinos. There one branch turns due eastward to Volo (ten miles), and the other bends around southwestward to Pharsalos. Valestinos i self is picturesquely placed at the foot of the hills and abounds in trees. Just opposite Valestinos, and to the north, lies the village of Rizomylou. This was the Turkish headquarters at the first battle of Valestinos on April 30th and was six miles southeast of Gherli and about three and a half miles north of Valestinos. In front and to the right of Rizomylou extended a thick, umbrageous wood for at least two miles toward Valestinos and the Greek position. The wood varied in width from two hundred to eight hundred yards. It would have been excellent cover for the Turks in an advance, but in neither battle did they use it. There were Greek intrenchments in the wood; and on the 30th its southern end was full of Greeks.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.