They were inured to hardships; they were at home in the woods; their relations with the Indians were of the happiest.

Continuing Fur Companies Abolished,

our selection from The Canadian Northwest: Its History And Its Troubles From The Early Days Of The Fur Trade To The Era Of The Railway And The Settler by G. Mercer Adam published in 1885. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Fur Companies Abolished.

Time: 1869

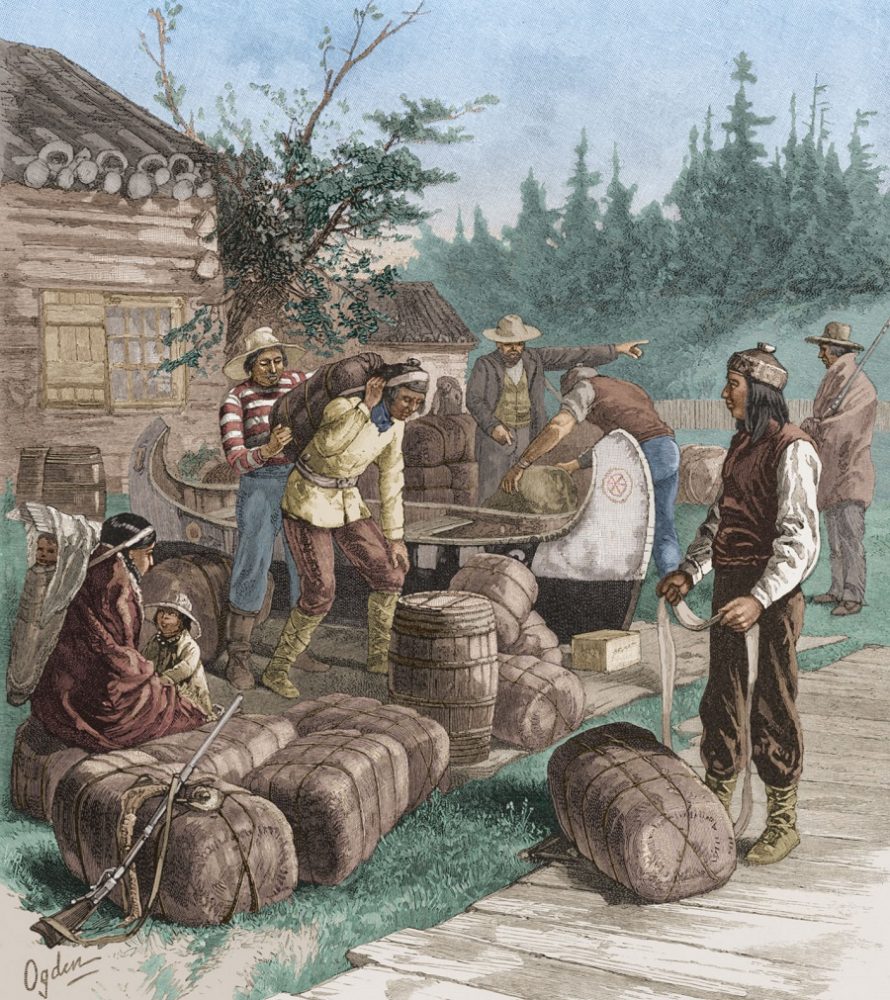

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

At the time of which we write, the Métis were almost entirely of French extraction, and were exclusively in the employ of the Northwest Company. At a later date, when the Hudson Bay Company began to trade in the south, an English, in contradistinction to a French half-breed race, in process of time sprang up. But as yet the half-breed was of French descent and owned allegiance to the Canadian company. To that company he naturally looked for employment; and he took to its service not only with alacrity but with ancestral pride. For his duties he was admirably fitted; for the half-breed possesses, in addition to the Frenchman’s versatility and ready resource, the Indian’s skill as a canoeist and his intuitive knowledge of the woods. The pride and stately dignity of the old French noblesse, and the magnificence of the Highland laird, who had now become an opulent fur-trader and possessor of large interests in the vast domain of the west, attracted the eye and won the heart of the simple child of the woods. This was true, indeed, not only of the half-breed, but of the full-blooded Indian. To the French both were drawn by characteristics of race which found no counterpart in the English. The French race was quick to merge into the Indian, and to pick up the habits, and not infrequently the vices, of the dusky children of the woods.

Such were the characteristics of the French Canadian and the half-breed who eagerly entered the employment of the Northwest Fur Company and worked long and unweariedly in its interests. For a time no other race or class of men could have been more serviceable to the company. They were inured to hardships; they were at home in the woods; their relations with the Indians were of the happiest; and they were never home sick or out of humor with their surroundings. Furthermore, they were always loyal to the company.

French trading operations were always joined with the motive of discovery. It was the invariable policy of the French Government, through its representatives at Quebec, to encourage geographical research and advance the possessions of the Crown. As early at 1717 M. De la Noue, a young French lieu tenant, was commissioned by M. De Vaudreuil, the Governor, to proceed to the west on a mission of trade and discovery. By this and the enterprises that immediately followed it, the whole vast interior, as far west as the Rocky Mountains, became known to the French; and in the region they speedily established their forts. In 1731 they erected Fort St. Pierre at the discharge of Rainy Lake, and in the following year founded Fort St. Charles on the Lake of the Woods and Fort Maurepas on the Winnipeg. In 1738 all the district of the Assiniboine was within the area of their operations, and Fort la Reine, on the St. Charles, and Fort Bourbon, on the Riviere des Biches, were established. Five years later the Vérendryes took possession of the Upper Mississippi and ascended the Saskatchewan in the interest of French trade. In 1766 the famous post of Michilimackinac, at the entrance of the Lac des Illinois (Michigan), was established. Other parts of the continent were also covered by the operations of the French traders and discoverers.

Hudson Bay had early been reached by way of the Saguenay and Lake St. John, by the Ottawa, and by Lakes Nipigon and Winnipeg. The Kaministiquia, at the head of Lake Superior, was the base of supplies for operations in the west, and the great rallying-place of the French trader and voyageur. In short, the whole country was probed and made known to the outer world by the enterprise of the French and the French Canadians. As a consequence any maps of the interior that were at all trust worthy were those of the French: the charts of the English, until long after the Conquest, were ludicrously inaccurate. Hence the opposition to the assumptions of the Hudson Bay Company, and the hostile rivalry which it engendered. After the Con quest, it is true, the French for a time abandoned their western possessions; but the old trading habit returned, stimulated by the sturdy Scotch and the organization of the Canadian Nor’ westers. The success of this company was remarkable. It had, however, its periods of trade depression and its years of disaster. A scourge of smallpox sometimes broke out among the Indians, and for the season destroyed its trade. Again, there were great floods in the west, and trade was impeded, if not wholly lost. Then came the era of strife with the Red River colony and collision with the Hudson Bays. In these engagements forts were fired and fur-depots destroyed. For a time hostilities were keen and continuous, and on both sides ruinous. Finally, the Hudson Bays and the Nor’westers coalesced; and from 1821 the amalgamated corporations traded under the old English title and charter of the Hudson Bay Company. This coalition gave great strength to the united company; it brought it an accession of capable traders and intelligent voyageurs and discoverers. In the service of the Northwest Company were men—Alexander Mackenzie and David Thompson among the number—whose names will be forever identified with discovery in the Northwest.

To the fur trade we chiefly owe the opening up of the vast region embraced in the Dominion of Canada, from the slender thread of settlement on the banks of the St. Lawrence westward to the Pacific, and from the shores of Hudson Bay to the 49th parallel, which in 1846 became the international boundary. South of this line the principal voyages of exploration across the continent, at the beginning of the century, were the American expeditions in 1804-1806 of Lewis and Clark, up the Missouri and down the Columbia Rivers, and the later trading operations of John Jacob Astor, who established Astoria, the great western emporium of the fur trade. In this trade Astor laid the foundations of his colossal fortune. Closely following on these enterprises, and growing out of them, came the prolonged international controversy on the Oregon question, which from 1818 to 1846 formed a bone of contention between Great Britain and the United States. The treaty of 1846 established the Canadian boundary line and settled the question of the national owner ship of the northern California coast.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.