This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Dwelling in the Midst of Alarms.

Introduction

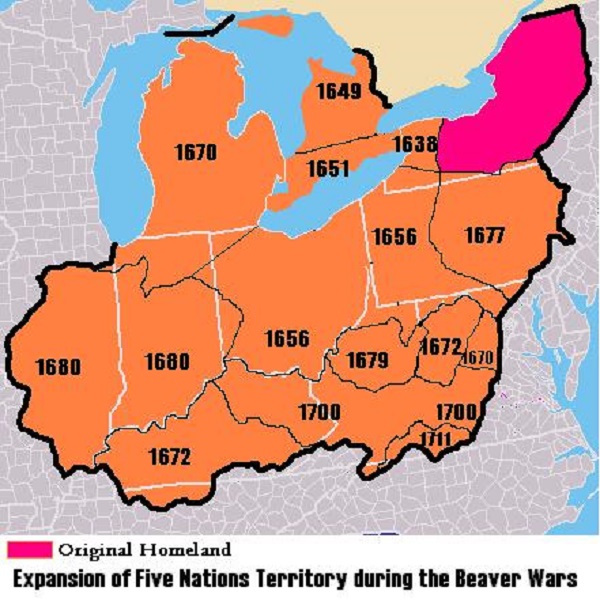

Just after Count Frontenac’s first administration of Canada (1672-1682), when the colony of New France was under the rule of De la Barre and his successor, the Marquis de Denonville, Montreal and its immediate vicinity suffered from the most terrible and bloody of all the Indian massacres of the colonial days. The hatred of the Five Nations for the French, stimulated by the British colonists of New York, under its governor, Colonel Dongan, was due to French forays on the Seneca tribes, and to the capture and forwarding to the royal galleys in France of many of the betrayed Iroquois chiefs. At this period the English on the seaboard began to extend their trade into the interior of the continent and to divert commerce from the St. Lawrence to the Hudson. This gave rise to keen rivalries between the two European races, and led the English to take sides with the Iroquois in their enmity to the French. The latter, at Governor Denonville’s instigation, sought to settle accounts summarily with the Iroquois, believing that the tribes of the Five Nations could never be conciliated, and that it was well to extirpate them at once. Soon the Governor put his fell purpose into effect. With a force of two thousand men, in a fleet of canoes, he entered the Seneca country by the Genesee River, and for ten days ravaged the Iroquois homes and put many of them cruelly to death. Returning by the Niagara River he erected and garrisoned a fort at its mouth and then withdrew to Québec. A terrible revenge was taken on the French colonists for these infamous acts, as the following article by M. Garneau shows.

This selection is from Histoire du Canada by François Xavier Garneau published in 1848. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

François Xavier Garneau (1809-1866) was civil servant and liberal who wrote a three-volume history of the French Canadian nation entitled Histoire du Canada

Time: 1689

Place: Montreal

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The situation of the colonists of New France during the critical era of M. Denonville’s administration was certainly anything but enviable. They literally “dwelt in the midst of alarms,” yet their steady courage in facing perils, and their endurance of privations when unavoidable, were worthy of admiration. A lively idea of what they had to resist or to suffer may be found by reading the more particular parts of the Governor’s dispatches to Paris. For instance, in one of these he wrote in reference to the raids of the Iroquois: “The savages are just so many animals of prey, scattered through a vast forest, whence they are ever ready to issue, to raven and kill in the adjoining countries. After their ravages, to go in pursuit of them is a constant but almost bootless task. They have no settled place whither they can be traced with any certainty; they must be watched everywhere, and long waited for, with fire-arms ready primed. Many of their lurking-places could be reached only by blood-hounds or by other savages as our trackers, but those in our service are few, and the native allies we have are seldom trustworthy; they fear the enemy more than they love us, and they dread, on their own selfish account, to drive the Iroquois to extremity. It has been resolved, in the present strait, to erect a fort in every seigniory, as a place of shelter for helpless people and live-stock, at times when the open country is overrun with ravagers. As matters now stand, the arable grounds lie wide apart, and are so begirt with bush that every thicket around serves as a point for attack by a savage foe; insomuch that an army, broken up into scattered posts, would be needful to protect the cultivators of our cleared lands.”

[Letter to M. Seignelai, August 10, 1688.]

Nevertheless, at one time hopes were entertained that more peaceful times were coming. In effect, negotiations with the Five Nations were recommenced; and the winter of 1687-1688 was passed in goings to and fro between the colonial authorities and the leaders of the Iroquois, with whom several conferences were holden. A correspondence, too, was maintained by the Governor with Colonel Dongan at New York; the latter intimating in one of his letters that he had formed a league of all the Iroquois tribes, and put arms in their hands, to enable them to defend British colonial territory against all comers.

The Iroquois confederation itself sent a deputation to Canada, which was escorted as far as Lake St. François by twelve hundred warriors — a significant demonstration enough. The envoys, after having put forward their pretensions with much stateliness and yet more address, said that, nevertheless, their people did not mean to press for all the advantages they had the right and the power to demand. They intimated that they were perfectly aware of the comparative weakness of the colony; that the Iroquois could at any time burn the houses of the inhabitants, pillage their stores, waste their crops, and afterward easily raze the forts. The Governor-general, in reply to these–not quite unfounded–boastings and arrogant assumptions, said that Colonel Dongan claimed the Iroquois as English subjects, and admonished the deputies that, if such were the case, then they must act according to his orders, which would necessarily be pacific, France and England not now being at war; whereupon the deputies responded, as others had done before, that the confederation formed an independent power; that it had always resisted French as well as English supremacy over its subjects; and that the coalesced Iroquois would be neutral, or friends or else enemies to one or both, at discretion; “for we have never been conquered by either of you,” they said; adding that, as they held their country immediately from God, they acknowledge no other master.

It did not appear, however, that there was a perfect accordance among the envoys on all points, for the deputies from Onnontaguez, the Onneyouths, and Goyogouins agreed to a truce on conditions proposed by M. Denonville; namely, that all the native allies of the French should be comprehended in the treaty. They undertook that deputies [others than some of those present?] should be sent from the Agniers and Tsonnouthouan cantons, who were then to take part in concluding a treaty; that all hostilities should cease on every side, and that the French should be allowed to revictual, undisturbed, the fort of Cataracoui. The truce having been agreed to on those bases, five of the Iroquois remained (one for each canton), as hostages for its terms being observed faithfully. Notwithstanding this precaution, several roving bands of Iroquois, not advertised, possibly, of what was pending, continued to kill our people, burn their dwellings, and slaughter live-stock in different parts of the colony; for example, at St. François, at Sorel, at Contrecoeur, and at St. Ours. These outrages, however, it must be owned, did not long continue, and roving corps of savages, either singly or by concert, drew off from the invaded country and allowed its harassed people a short breathing-time at least.

The native allies of the French, on the other hand, respected the truce little more than the Iroquois. The Abenaquis invaded the Agniers canton, and even penetrated to the English settlements, scalping several persons. The Iroquois of the Sault and of La Montagne did the like; but the Hurons of Michilimackinac, supposed to be those most averse to the war, did all they could, and most successfully, too, to prevent a peace being signed.

While the negotiations were in progress, the “Machiavel of the wilderness,” as Raynal designates a Huron chief, bearing the native name of Kondiarak, but better known as Le Rat in the colonial annals, arrived at Frontenac (Kingston), with a chosen band of his tribe, and became a means of complicating yet more the difficulties of the crisis. He was the most enterprising, brave, and best-informed chief in all North America; and, as such, was one courted by the Governor in hopes of his becoming a valuable auxiliary to the French, although at first one of their most formidable enemies. He now came prepared to battle in their favor, and eager to signalize himself in the service of his new masters. The time, however, as we may well suppose, was not opportune, and he was informed that a treaty with the Iroquois being far advanced, and their deputies on the way to Montreal to conclude it, he would give umbrage to the Governor-general of Canada should he persevere in the hostilities he had been already carrying on.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.