The French in the south were materially interfering with its trade,

Continuing Fur Companies Abolished,

our selection from The Canadian Northwest: Its History And Its Troubles From The Early Days Of The Fur Trade To The Era Of The Railway And The Settler by G. Mercer Adam published in 1885. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Fur Companies Abolished.

Time: 1869

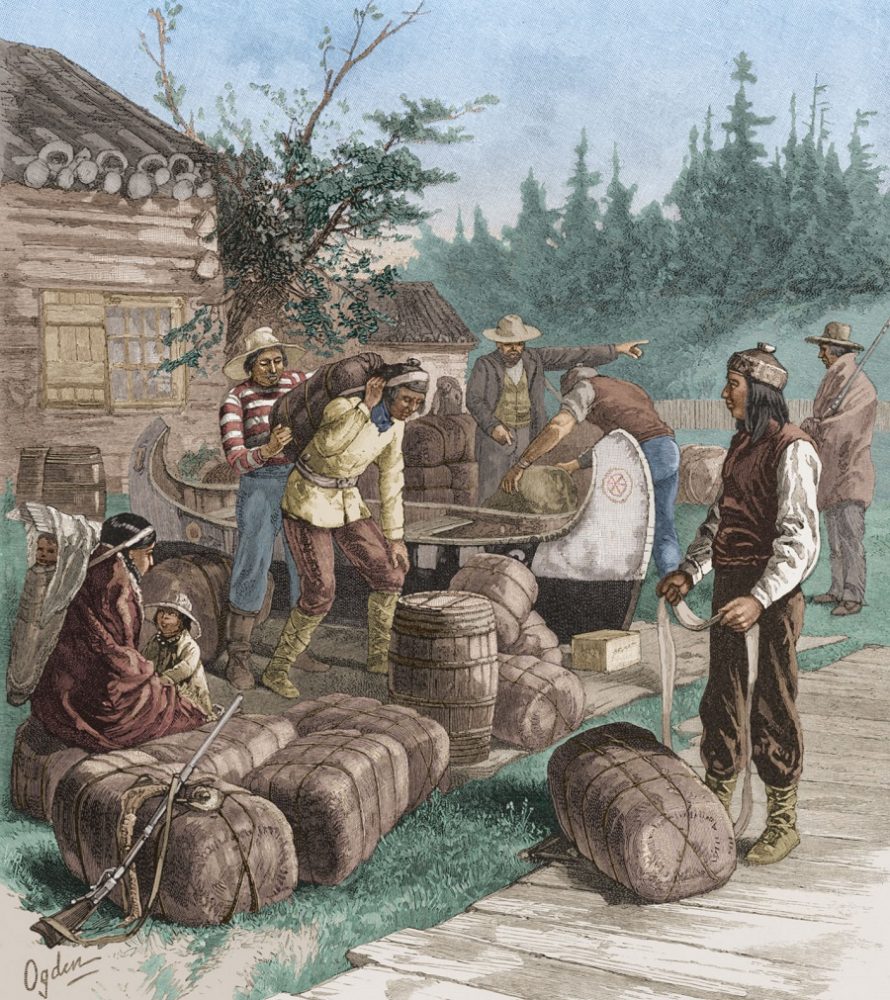

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Meanwhile the French were active in the lower waters of the continent; for in 1672 La Salle had discovered the Mississippi, Joliet and Marquette had traced the outline of the Georgian Bay and Lake Superior, and Father Hennepin had seen and made a chart of the Falls of Niagara. Afterward M. Du Luth and M. De la Vérendrye penetrated into all the bays of Lake Superior, and the latter, in 1632, constructed a fort on the Lake of the Woods. At the period of the Conquest the French had done far more to discover and open up what is now the Canadian Northwest than the English. Up to 1763 they had gone as far west as the Assiniboine and the Saskatchewan. They had established Fort Maurepas on the Winnipeg, Fort Dauphin on Lake Manitoba, Fort Bourbon on Cedar Lake, and Fort a la Corne below the forks of the Saskatchewan. The Hudson Bay Company, on the contrary, had done little to invade the continent. The trade of the company hardly extended beyond the shores of Hudson Bay, or, at most, a short distance down the Albany River and the Churchill. They were inactive in their work, and for a time found their charter ineffectual to prevent interlopers from sharing the profits of the growing fur-trade. Petitioning Parliament, they now and again got a confirmation of their title and increased powers of trade; though one of the objects for which the company had originally secured its charter, the prosecution of discovery in the Arctic regions, had been little promoted. Hence enemies in Parliament repeatedly tried to limit the company’s privileges and to annul its charter. Instigated by these enemies rival traders fitted out expeditions to Hudson Bay to embarrass the company and seize some portion of its trade. The fate of these expeditions was, however, ad verse to rivalry; for no better sport was found for the employees of the privileged company than to board the vessels, capture their crews, and wreck the craft on the shores of the Bay.

But not thus could the Hudson Bay Company suppress competition from the interior. The French in the south were materially interfering with its trade, and the company found that to retain it its employees had to organize corps of traders and voyageurs, who would ascend the rivers and establish posts in the valleys of the Red River and Saskatchewan and the region of the Great Lakes. This was a matter that entailed no little difficulty and risk. To the “Hudson Bays” the interior was an unknown wilderness; and as yet they had not learned the craft of the Indian woodsman or the skill of the French coureur de bois. But they had more to contend with than the tyranny of nature and the perils of the way. The colony of New France by this time had grown to considerable proportions, and the French trader was to be met with all over the country. M. De Vaudreuil gives the population of New France in 1760 as 70,000, exclusive of voyageurs and those engaged in trade with the Indians. The French, moreover, held the two great waterways to the West—the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi. From these inlets their countrymen had spread far to the northwest; and in their traffic with the Indians of the Red River and Saskatchewan districts they had cut off much trade that previously had found its way to the Hudson Bay posts on the Albany, the Nelson, the Churchill, and the Severn. Presently war with the English again broke out, and from across the Atlantic came the invading forces of Britain and contingents from her colonies on the coast. To some extent this withdrew the French traders to their posts on the meadows of the Mississippi and to those on the Ohio and the Alleghany. The time was therefore favorable to the Hudson Bay Company employees in again diverting the fur-trade to the old posts by the northern sea. More effectually to secure this trade, the company sent its servants to establish posts in the south, and by the year 1774 Cumberland House was founded on the Saskatchewan, and at a somewhat later day an extensive circle of forts, tributary to that at York Factory, was established and equipped.

Of the character and trade of these forts we get an intelligent idea from a graphic sketch of the Hudson Bay Company, in an English periodical published in 1870. * The writer is an old employee of the company:

[* “The Story of a Dead Monopoly” Cornhill Magazine, August, 1870.]

A typical fort of the Hudson Bay Company was not a very lively sort of affair at best. Though sometimes built on a com manding situation at the head of some beautiful river and backed by wave after wave of dark pine forest, it was not un picturesque in appearance. Fancy a parallelogram, enclosed by a picket twenty-five or thirty feet in height, composed of upright trunks of trees, placed in a trench, and fastened along the top by’ a rail, and you have the enclosure. At each corner was a strong bastion, built of squared logs, and pierced for guns that could sweep every side of the fort. Inside this picket was a gallery running right around the enclosure, just high enough for a man’s- head to be level with the top of the fence. At intervals, all along the side of the picket, were loopholes for musketry, and over the gateway was another bastion, from which shot could be poured on any party attempting to carry the gate. Altogether, though incapable of withstanding a ten-pounder for two hours, it was strong enough to resist almost any attack the Indians could bring against it. Inside this enclosure were the store houses, the residences of the employees, wells, and sometimes a good garden. All night long a voyageur would, watch by watch, pace around this gallery, crying out at intervals, with a quid of tobacco in his cheek, the hours and the state of the weather. This was a precaution in case of fire, and the hour calling was to prevent him falling asleep for any length of time. Some of the less important and more distant outposts were only rough little log-cabins in the snow, without picket or other enclosure, where a “postmaster’ resided to superintend the affairs of the company.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.