The Turkish infantry were all armed with the Martini-Henry rifle and the long bayonet.

Continuing Greco-Turkish War of 1897,

our selection from Battlefields of Thessaly by Sir Ellis Ashmead Bartlett published in 1897. The selection is presented in seven easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Greco-Turkish War of 1897.

Time: 1897

Place: Thessaly and Crete

CC 0 image from Wikipedia.

The Turkish campaign in Thessaly divides itself both chrono logically and geographically into three phases. The first consists of the declaration of war and the battles along the frontier ridges for the possession of the mountain boundary. This covers the period between April 16th and April 22nd, when the Turkish columns had forced the Greeks off the mountain barriers and had themselves got a foothold on the edge of the Thessalian plain.

The second phase or period covers the battles of Mati-Deliler and the passage of the Reveni defile, with the consequent capture of Tournavos and Larissa. This embraces the days between April 23rd and May 4th and includes the first battle of Valestinos. During this period Edhem Pacha finally broke down the resistance of the Greek army in the open, and he occupied the capital and the whole northern half of Thessaly. The Greek forces retreated in panic haste to the Valestinos-Pharsalos-Trikkala line, and were allowed to intrench themselves there. Edhem re mained practically inactive from April 25th, when Larissa fell, down to May 5th, when he attacked the Greeks all along their new line. The unsuccessful assault made by Hakki Pacha upon Valestinos on April 30th was not intended by the Nushir to be more than a reconnaissance, though it developed finally into a bloody battle.

The third phase covers the remainder of the war, the period between May 5th and May 17th, when the Greeks were driven out of Southern Thessaly by the battles of Valestinos, Pharsalos, and Domokos. This period was marked by the largest and most sanguinary conflicts, and by the heaviest losses to the Turks. Their losses at Valestinos and Pharsalos probably exceeded those of all the rest of the campaign in Thessaly. The Greek losses, too, were heavy both at Pharsalos and Valestinos.

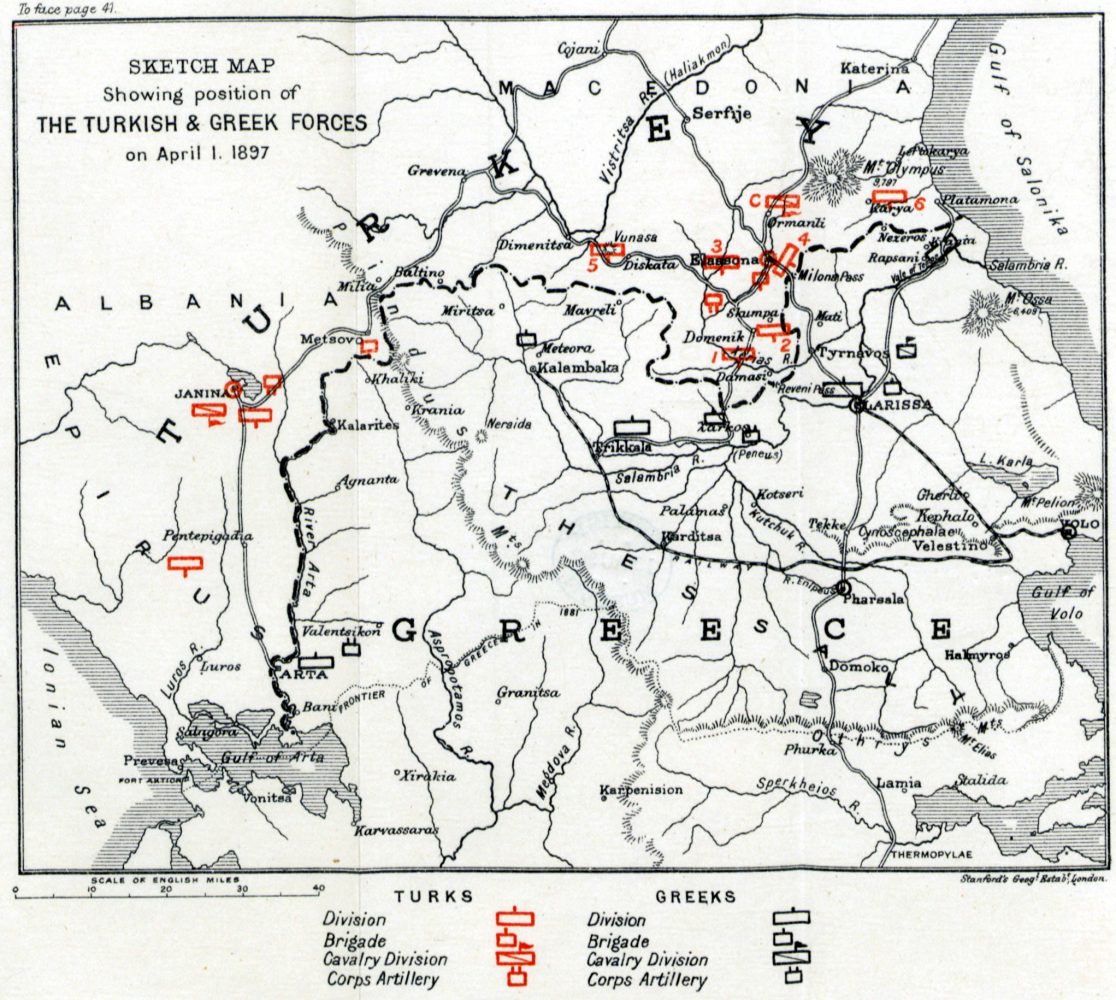

When the war began, there were six Turkish divisions, numbering about ninety thousand men, at or within striking distance of the frontier. There were also the weak cavalry division commanded by Suleiman Pacha at Ormanli, and twelve batteries of artillery under Riza Pacha at Elassona. In addition to these, the Seventh division under Husni Pacha reached Elassona in the first week of May, and the Eighth division was mobilized there just at the close of the war. Another corps of about ten thousand men under Islam Pacha was assembled at Diskata. There were also two divisions in Epirus which together numbered about thirty thousand men.

The Turkish infantry were all armed with the Martini-Henry rifle and the long bayonet — a most excellent weapon. One brigade only of the Second division, Neschat Pacha’s, had the new Mauser rifle, and this brigade suffered heavily at Domokos.

Only a small portion of the Turkish force belonged to the regular army on active service; that is, to the Nizams. Three- quarters were Redifs, or reserve men, between the ages of twenty- five and fifty. The average age was between thirty and thirty- five. These Redifs were strong, well-grown, hardy peasants, who seemed capable of enduring any fatigue and who rarely succumbed to disease. There were also from eight thousand to ten thousand Albanians. One of the finest battalions was that of Trebizond, a magnificent body of men, all as tall as the British Grenadier Guards, and much more hardy.

The cavalry was small in number, but excellent in quality. The men were tall, stalwart troopers and good horsemen. The horses were small and ragged-looking, between fourteen and fifteen hands, but extraordinarily wiry, enduring, and sure-footed. They had a good deal of Arab blood and stood an amount of hard work that would have exhausted English horses in a few days. The Greeks had an idea that the Turkish cavalry were Circassians, because they wore black lambskin caps, or kalpacks, and they were in mortal terror of these soi-disant Circassians but not more than a quarter of the troopers were Circassians. They carried long swords, and a rifle and shoulder-belt of cartridges.

The Turkish artillery was good; the guns, 3-inch Krupps, with 12-lb. shell; and the limbers, carriages, and guns themselves were all in good condition. Each battery had six guns, sixty horses, and eighty men. The horses were excellent; but the practice made by the artillery during the war was not good. There were three batteries of horse-artillery (9-pounders) with the cavalry division, and three batteries of mountain- guns on mules. The engineering of the army was not very efficient. The transport was all done by horses or mules and the telegraph was very slow and inadequate. The medical staff and hospital service were, so far as I could judge, good. The surgeons that I saw were willing and skillful, and the supply of instruments, tents, and antiseptics adequate.

The general staff of the Turkish army in Thessaly was excellent. Most of the best men had been trained in Germany and spoke German and French. The divisional generals were mostly inferior, and their staffs were by no means as good as they should have been.

The Greek army was about two- thirds as large as that of the Turks. Probably never more than ninety thousand men were under arms in Thessaly and Epirus. The Greek rifle was the Gras, of a French pattern, with a bolt action. Some of the Euzonoi (“mountaineers”) were fine men and good shots; these fought well on occasions, notably at Melouna, Valestinos, and Pharsalos. But the mass of the Greek soldiers made off as soon as the Turkish advances came within six hundred yards.

The artillery was called good, though deficient in numbers. The guns were Krupp, and the officers were fairly well trained. There was very little cavalry. The transport and supply ser vices were wretched and the reserves of ammunition deficient. There was a small foreign legion of about five hundred men, made up chiefly of Italians and English. Most of the former behaved badly at first, though they improved with practice. The English seem to have shown fair cohesion and courage. The irregular troops, for which the Ethnike Hetairia were responsible, were a nuisance and a weakness.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.