On April 17th the Sultan, in consequence of the Greek raids into Ottoman territory, and on the advice of his Council of State, declared war against Greece.

Continuing Greco-Turkish War of 1897,

our selection from Battlefields of Thessaly by Sir Ellis Ashmead Bartlett published in 1897. The selection is presented in seven easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Greco-Turkish War of 1897.

Time: 1897

Place: Thessaly and Crete

CC 0 image from Wikipedia.

Perhaps the most striking feature about the Turkish army is the extraordinary health of the average Turkish soldier. He comes from the finest physical material in the world — the temperate Ottoman peasantry of both Asia and Europe. Accustomed to living on bread and water, with no stimulants and little meat, in a fine climate and out of doors, the Turkish peasant has a constitution that defies fatigue and disease and can accomplish marvels on a minimum of food.

The courage of the Ottoman is at once hereditary and religious. Descended from generations of fighting men, who have rarely shown fear or avoided the face of an enemy, the Osmanli has an inborn ancestral pride and valor that give him a dauntless courage in battle. His religion, too, strengthens his natural bra very, for it teaches him that eternal bliss is the reward of those Ottomans who die in battle for their faith and their country.

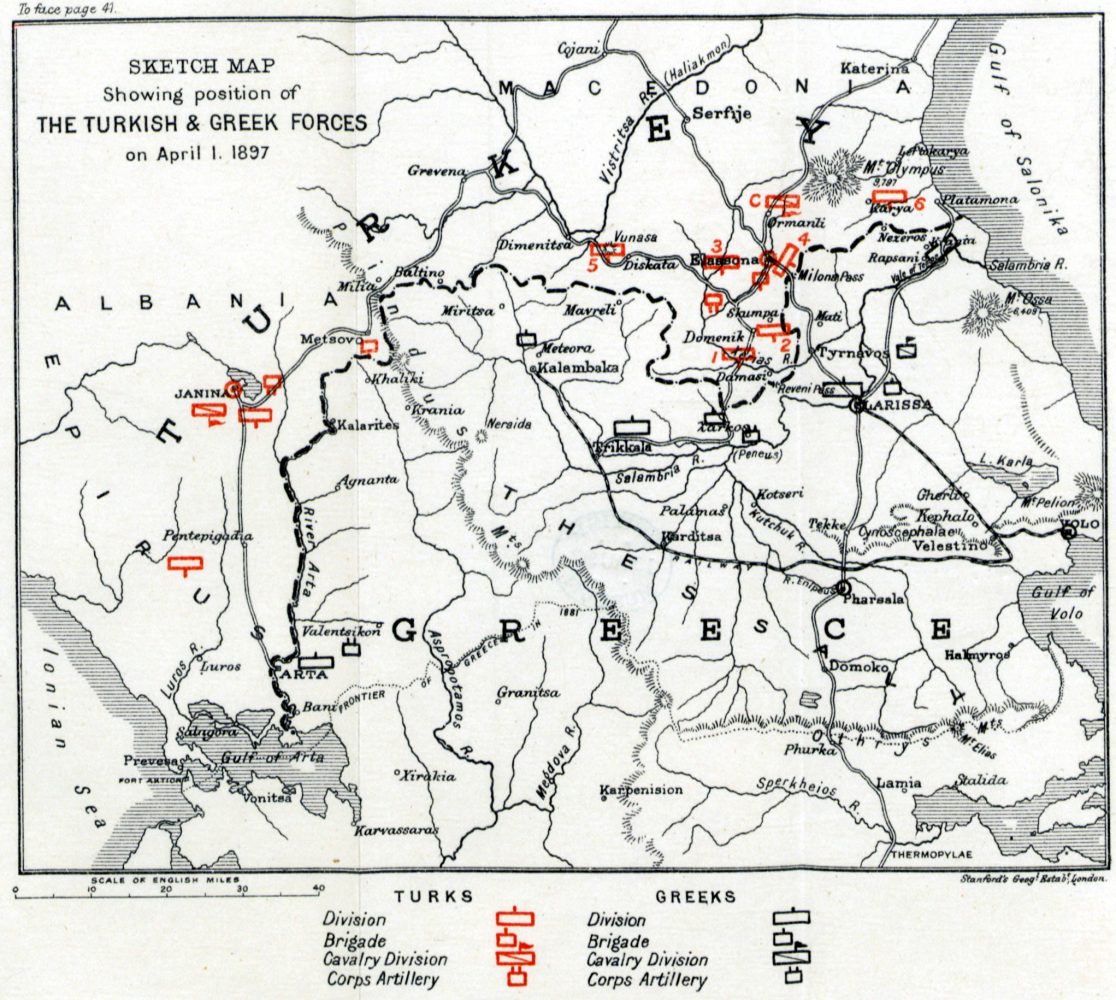

On April 17th the Sultan, in consequence of the Greek raids into Ottoman territory, and on the advice of his Council of State, declared war against Greece. Prince Mavrocordato, the Greek envoy at Constantinople, received his passports, the Turkish envoy at Athens was recalled, and Greek subjects residing in Turkey had fourteen days in which to remove from Ottoman soil. The immediate cause of the formal declaration of war was an in road of Greek regulars, on April 16th, into Ottoman territory at Karya, which lies north of the Vale of Tempe, near Lake Nezeros, and is three or four miles within Turkish territory. This almost developed into a battle on the 17th, and it took twelve battalions of Hamdi Pacha’s division to repel the Greek attack. A state of war had practically existed along the frontier since the Greek raids of April 9th.

Almost immediately the whole frontier broke out into flame and blood. A series of fierce conflicts took place between the two armies all along the boundary-line from Nezeros on the east to a point beyond Damasi on the southwest. In almost every case the Greeks took the offensive and at first gained some slight advantages. Thus, at Melouna, where the chief fighting took place, they surrounded the Turkish blockhouse and occupied the whole pass, and two battalions actually descended into the plain late at night and menaced Elassona itself. Their advance, however, was very brief. Haidar Pacha, commanding the Fourth division, attacked them in force and drove them up to the hilltops. Here, on the summit of the pass, a desperate conflict ensued. The Turkish blockhouse, with its garrison of fifty men, which had held its own all the time, was rescued. The Greek blockhouse, which faced it at a distance of less than one hundred yards, was taken and retaken four times before it was left in the hands of the Turks. The Greeks fought well at Melouna. They were mostly Euzonoi, and were superior in physique to the average Greek soldier, who is physically a very poor creature. The final blow was given to the Greek defense at Melouna by the advance of the Third Turkish division, under Memdouk Pacha, along the ridge to the right of the pass. The brigade commanded by Hafiz Pacha took three blockhouses southwest of that in Melouna itself, at the point of the bayonet.

The losses in these Melouna combats were considerable. The Turks lost more than two hundred wounded, and the Greeks loss must have been at least five hundred. At Athens it was estimated that the Greeks lost one thousand killed or wounded at Melouna; but they put down the Turkish loss as heavier. Here fell a gallant veteran, Hafiz Pacha, leading his brigade. The fol lowing account of Hafiz Pacha’s heroic death was given by Reuter’s correspondent:

QUOTE

“Among the dead is Hafiz Pacha, a veteran of the Russo-Turkish War. He rode bareheaded in advance of his men, and not all his eighty years could curb his ardor. His orderly begged him to dismount as the bullets began to whistle above the men but Hafiz’s only answer was: ‘In the war with Russia I never dismounted; why should I do so now? Forward, my children!’ A minute later he reeled, hit on his left arm and again, his staff begged him to dismount and retire to the rear. A second bullet shattered his right hand; a third messenger of death struck him in the throat, as he was cheering on his men, and, cutting the spinal cord, killed him instantly.”

On the far left Hamdi Pacha slowly drove back the Greeks that had invaded Turkish territory and attacked him at Karya. Reinforcements of artillery and two battalions of infantry were sent to him from Elassona. By the 22d the Greeks were in full retreat from the Nezeros and Rapsani districts. A portion of this Greek force retired southeastward, crossing the Peneius at the bridge below the Vale of Tempe, and went along the coast through Tsaghesi toward Volo. They broke down the bridge over the Peneius behind them — the only engineering attempt made by the Greeks in retreat to impede the advance of the enemy. The greater part of the Greek right wing fell back through the Rapsani Pass and joined the main body, then drawn up on the Deliler-Mati line in front of Tournavos.

Irregular fighting went on for three days along the heights southwestward from Melouna to Damasi. Here the two divisions of Neschat Pacha at Skumpa and Hairi Pacha at Damasi were engaged, first in resisting Greek attacks, and then in pressing the Greek assailants back through the Skumpa and Reveni passes into the Thessalian plain.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.