This artifice, a manifestation of the diabolic nature of its author, had too much of the success intended by it.

Continuing The Lachine Massacre,

our selection from Histoire du Canada by François Xavier Garneau published in 1848. The selection is presented in three easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Lachine Massacre.

Time: 1689

Place: Montreal

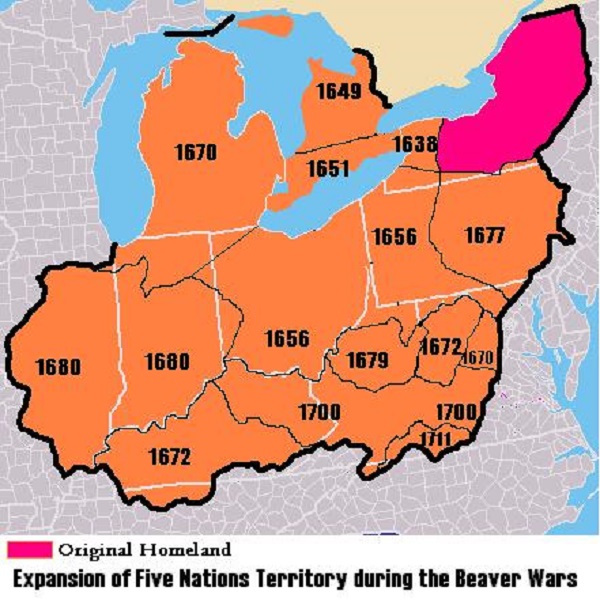

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The Rat was taken aback on hearing this to him unwelcome news but took care to hide his surprise and uttered no complaint. Yet was he mortally offended that the French should have gone so far in the matter without the concert of their native allies, and he at once resolved to punish them, in his own case, for such a marked slight. He set out secretly with his braves, laid an ambuscade near Famine Cove for the approaching deputation of Iroquois, murdered several and made the others his prisoners. Having done so, he secretly gloried in the act, afterward saying that he had “killed the peace.” Yet in dealing with the captives he put another and a deceptive face on the matter; for, on courteously questioning them as to the object of their journey, being told that they were peaceful envoys, he affected great wonder, seeing that it was Denonville himself who had sent him on purpose to waylay them!

To give seeming corroboration to his astounding assertions, he set the survivors at liberty, retaining one only to replace one of his men who was killed by the Iroquois in resisting the Hurons’ attack. Leaving the deputies to follow what course they thought fit, he hastened with his men to Michilimackinac, where he presented his prisoner to M. Durantaye, who, not as yet officially informed, perhaps, that a truce existed with the Iroquois, consigned him to death, though he gave Durantaye assurance of who he really was; but when the victim appealed to the Rat for confirmation of his being an accredited envoy, that unscrupulous personage told him he must be out of his mind to imagine such a thing! This human sacrifice offered up, the Rat called upon an aged Iroquois, then and long previously a Huron captive, to return to his compatriots and inform them from him that while the French were making a show of peace-seeking, they were, underhand, killing and making prisoners of their native antagonists.

This artifice, a manifestation of the diabolic nature of its author, had too much of the success intended by it, for, although the Governor managed to disculpate himself in the eyes of the more candid-minded Iroquois leaders, yet there were great numbers of the people who could not be disabused, as is usual in such cases, even among civilized races. Nevertheless the enlightened few, who really were tired of the war, agreed to send a second deputation to Canada; but when it was about to set out, a special messenger arrived, sent by Andros, successor of Dongan, enjoining the chiefs of the Iroquois confederation not to treat with the French without the participation of his master, and announcing at the same time that the King of Great Britain had taken the Iroquois nations under his protection. Concurrently with this step, Andros wrote to Denonville that the Iroquois territory was a dependency holden of the British, and that he would not permit its people to treat upon those conditions already proposed by Dongan.

This transaction took place in 1688; but before that year concluded, Andros’ “royal master” was himself superseded, and living an exile in France. * Whether instructions sent from England previously warranted the polity pursued by Andros or not, his injunctions had the effect of instantly stopping the negotiations with the Iroquois, and prompting them to recommence their vengeful hostilities. War between France and Britain being proclaimed next year, the American colonists of the latter adopted the Iroquois as their especial allies, in the ensuing contests with the people of New France.

[* In 1688 Andros was appointed Governor of New York and New England. The appointment of this tyrant, and the annexation of the colony to the neighboring ones, were measures particularly odious to the people.–ED.]

Andros, meanwhile, who adopted the policy of his predecessor so far as regarded the aborigines if in no other respect, not only fomented the deadly enmity of the Iroquois for the Canadians, but tried to detach the Abenaquis from their alliance with the French, but without effect in their case; for this people honored the countrymen of the missionaries who had made the Gospel known to them, and their nation became a living barrier to New France on that side, which no force sent from New England could surmount; insomuch that the Abenaquis, some time afterward, having crossed the borders of the English possessions, and harassed the remoter colonists, the latter were fain to apply to the Iroquois to enable them to hold their own.

The declaration of Andros, and the arming of the Iroquois, now let loose on many parts of Canada, gave rise to a project as politic, perhaps, as it was daring, and such as communities when in extremity have adopted with good effect; namely, to divert invasion by directly attacking the enemies’ neighboring territories. The Chevalier de Callières, with whom the idea originated, after having suggested to Denonville a plan for making a conquest of the province of New York, set out for France, to bring it under the consideration of the home government, believing that it was the only means left to save Canada to the mother-country.

It was high time, indeed, that the destinies of Canada were confided to other directors than the late and present ones, left as the colony had been, since the departure of M. de Frontenac, in the hands of superannuated or incapable chiefs. Any longer persistency in the policy of its two most recent governors might have irreparably compromised the future existence of the colony. But worse evils were in store for the latter days of the Denonville administration; a period which, take it altogether, was one of the most calamitous which our forefathers passed through.

At the time we have now reached in this history an unexpected as well as unwonted calm pervaded the country, yet the Governor had been positively informed that a desolating inroad by the collective Iroquois had been arranged, and that its advent was imminent; but as no precursive signs of it appeared anywhere to the general eyes, it was hoped that the storm, said to be ready to burst, might yet be evaded. None being able to account for the seeming inaction of the Iroquois, the Governor applied to the Jesuits for their opinion on the subject. The latter expressed their belief that those who had brought intelligence of the evil intention of the confederacy had been misinformed as to facts, or else exaggerated sinister probabilities. The prevailing calm was therefore dangerous as well as deceitful, for it tended to slacken preparations which ought to have been made to lessen the apprehensions of coming events which threw no shadow before.

The winter and the spring of the year 1688-1689 had been passed in an unusually tranquil manner, and the summer was pretty well advanced when the storm, long pent up, suddenly fell on the beautiful island of Montreal, the garden of Canada. During the night of August 5th, amid a storm of hail and rain, fourteen hundred Iroquois traversed Lake St. Louis, and disembarked silently on the upper strand of that island. Before daybreak next morning the invaders had taken their station at Lachine in platoons around every considerable house within a radius of several leagues. The inmates were buried in sleep–soon to be the dreamless sleep that knows no waking, for too many of them.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.