The Northwest Fur Company of Montreal was for nearly forty years an active and formidable rival of the Hudson Bay Company.

Continuing Fur Companies Abolished,

our selection from The Canadian Northwest: Its History And Its Troubles From The Early Days Of The Fur Trade To The Era Of The Railway And The Settler by G. Mercer Adam published in 1885. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Fur Companies Abolished.

Time: 1869

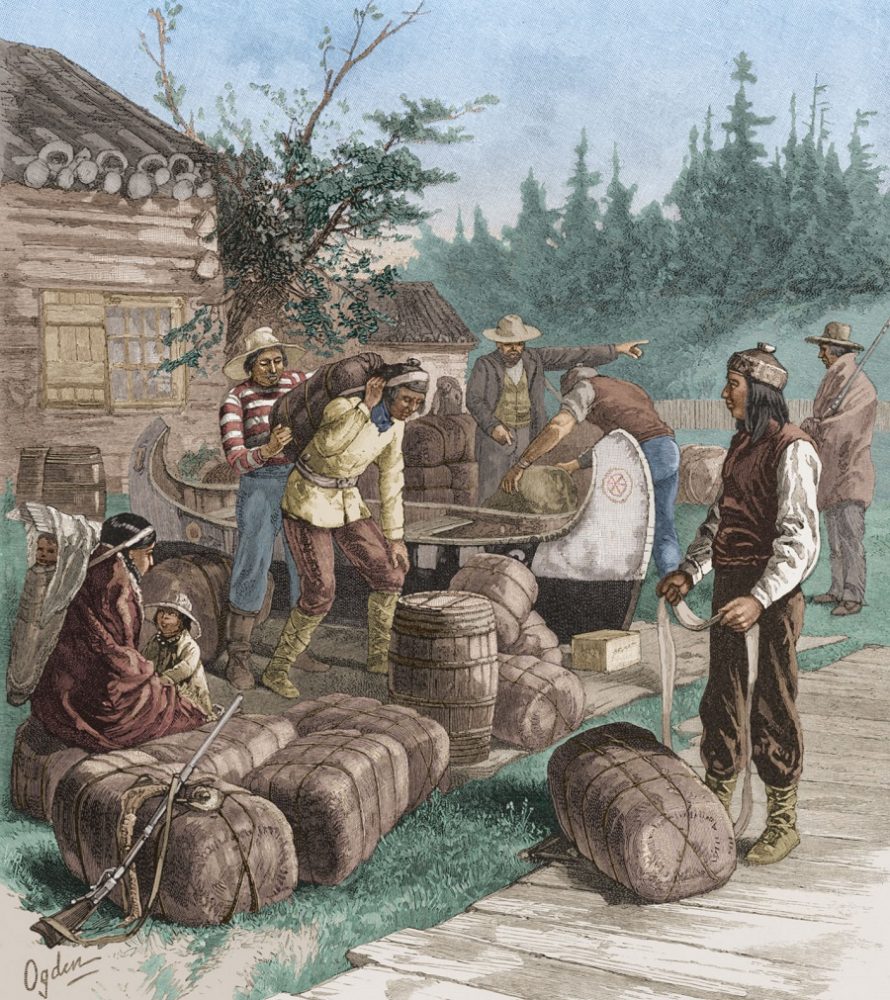

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Continuing yesterday’s quote:

The mode of trading was peculiar. It was a system of barter, a ‘made’ or “typical’ beaver-skin being the standard of trade. This was, in fact, the currency of the country. Thus an Indian arriving at one of the company’s establishments with a bundle of furs which he intends to sell, proceeds, in the first instance, to the trading-room: there the trader separates the furs into lots, and, after adding up the amount, delivers to the Indian little pieces of wood, indicating the number of ‘made-beavers’ to which his ‘hunt” amounts. He is next taken to the store room, where he finds himself surrounded by bales of blankets, slop-coats, guns, scalping-knives, tomahawks (all made in Birmingham), powder-horns, flints, axes, etc. Each article has a recognized value in ‘made beavers’; a slop-coat, for example, may be worth five ‘made beavers, for which the Indian delivers up twelve of his pieces of wood; for a gun he gives twenty; for a knife two; and so on, until his stock of wooden cash is ex pended. After finishing he is presented with a trifle besides the payment for his furs and makes room for someone else.”

Of these trading-establishments of the Hudson Bay Company the writer adds:

There were in 1860 more than 150, in charge of twenty-five chief factors and twenty-eight chief traders, with 150 clerks and 1200 other servants. The trading-districts of the company were thirty-eight, divided into five departments, and extending over a country nearly as large as Europe, though thinly peopled by about 160,000 natives, Esquimaux, Indians, and half-breeds.”

The Northwest Fur Company of Montreal was for nearly forty years an active and formidable rival of the Hudson Bay Company. It was a Canadian venture, a private joint-stock company, composed of French, Scottish, and, to some extent, half-breed traders, without charter, or, so far as we can make out, license from the Government. Its object was to pursue the peltry trade, and to traffic with the Indians. Next to the Hud son Bay Company, it was the most powerful trading-organization that ever entered the field of commerce in the Northwest. Its history is marked by chronic feuds with the employees of its great English rival, and by a sanguinary conflict with Lord Selkirk’s settlement on Red River. In its encounter with the latter, twenty-two lives were lost, including the Hudson Bay governor. Toward the colony of the Scottish nobleman it pursued a relentless, cruel policy. In its hostility it was actuated by the same spirit of opposition that actuated the English company in resisting the entrance of a rival in its own field. This jealousy it became the purpose of the Hudson Bay Company to inflame. By every art it embittered the feeling between the Nor’westers and the colony; and afterward it readily lent its aid as an ally in the strife.

The feud with the Scotch immigrants of the Selkirk colony was only an incident, though a prominent one, in the history of the conflict between the two trading-organizations, locally known as the “Nor’westers” and the “Hudson Bays.” The intrusion of the former into what was deemed the exclusive possessions of the latter was the occasion of a long and bitter strife. The Northwest Company, organized in 1783, was not long in building up a successful trade, for its operations were conducted with skill, vigor, and enterprise. From the period of the Conquest to that of the establishment of the Canadian company, many private traders had penetrated into the Northwest. The head of Lake Superior was their common rendezvous. Thence the usual route to the west was by Rainy River, the Lake of the Woods, and the Winnipeg. Reaching Red River they gradually extended their operations as far west as the Saskatchewan, and, ere long, to the forks of the Athabasca. There they intercepted the trade that was wont to seek the Hudson Bay posts on the Churchill. This rivalry at last woke the English company from its lethargy, and it determined to send traders inland to recover its monopoly. By this time, however, the Montreal company was not only in the field, it was strongly entrenched. Already it had possession of the trade of Red River and had established a fort at the mouth of the Souris.

But the Canadian company was not only active, it was shrewd. The principle on which it was organized was cooperative; it gave its servants a share in the profits of the business. The effect of this was to strengthen the company and to make it a formidable rival. Every year saw its enterprising traders extend their operations farther west. This could not go on undisturbed. The Hudson Bay Company, now fully alarmed, bestirred itself to oppose it. Wherever the Nor’westers constructed a fort, the Hudson Bays established a rival one. Each claimed a right to the territory, the one by virtue of its charter, the other by right of discovery and first occupancy.

Now began a many years’ conflict. The Hudson Bay Company was a newcomer in the territory; the French had been actively in possession for more than a century. As early as 1627, forty years before the Hudson Bays had obtained their charter, a body of French traders, known as the “One Hundred Associates,” was trafficking on the plains of the Northwest. King Charles’s deed to the Hudson Bay Company seems, indeed, to have been issued with a knowledge of this circumstance, for it cedes only those lands “not possessed by the subjects of any other Christian King or State.” The French historian Charlevoix, who visited Canada in 1720, speaks scornfully of the pretensions of the English in these regions. The Nor’westers had another and a demonstrative ally in their employees, the Métis, or Bois-brules, who, of course, took the French view of the case. These “half-breeds,” who to-day form a considerable and an unsettled portion of the population of the Northwest, were the progeny of the early French voyageur who had mated with the Indian. Later, the Scotch trader and company’s employee was not loath to follow the example of his French countryman.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.