This series has seven easy 5-minute installments. This first installment: Before the War.

Introduction

The peoples of the lands of present times Greece and Turkey have engaged in hostilities since the Trojan War. Sometimes the people of Greece conquered the people of Asia Minor (present Turkey) – like during Alexander the Great’s time – and then after the Ottoman Turks conquered both areas. Greeks won a war of independence in the 1820’s; hostilities simmered thereafter.

In the closing years of the century, those hostilities broke out into war.

This selection is from Battlefields of Thessaly by Sir Ellis Ashmead Bartlett published in 1897. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Sir Ellis Ashmead Bartlett (1849-1902) was a conservative member or the British Parliament.

Time: 1897

Place: Thessaly and Crete

CC 0 image from Wikipedia.

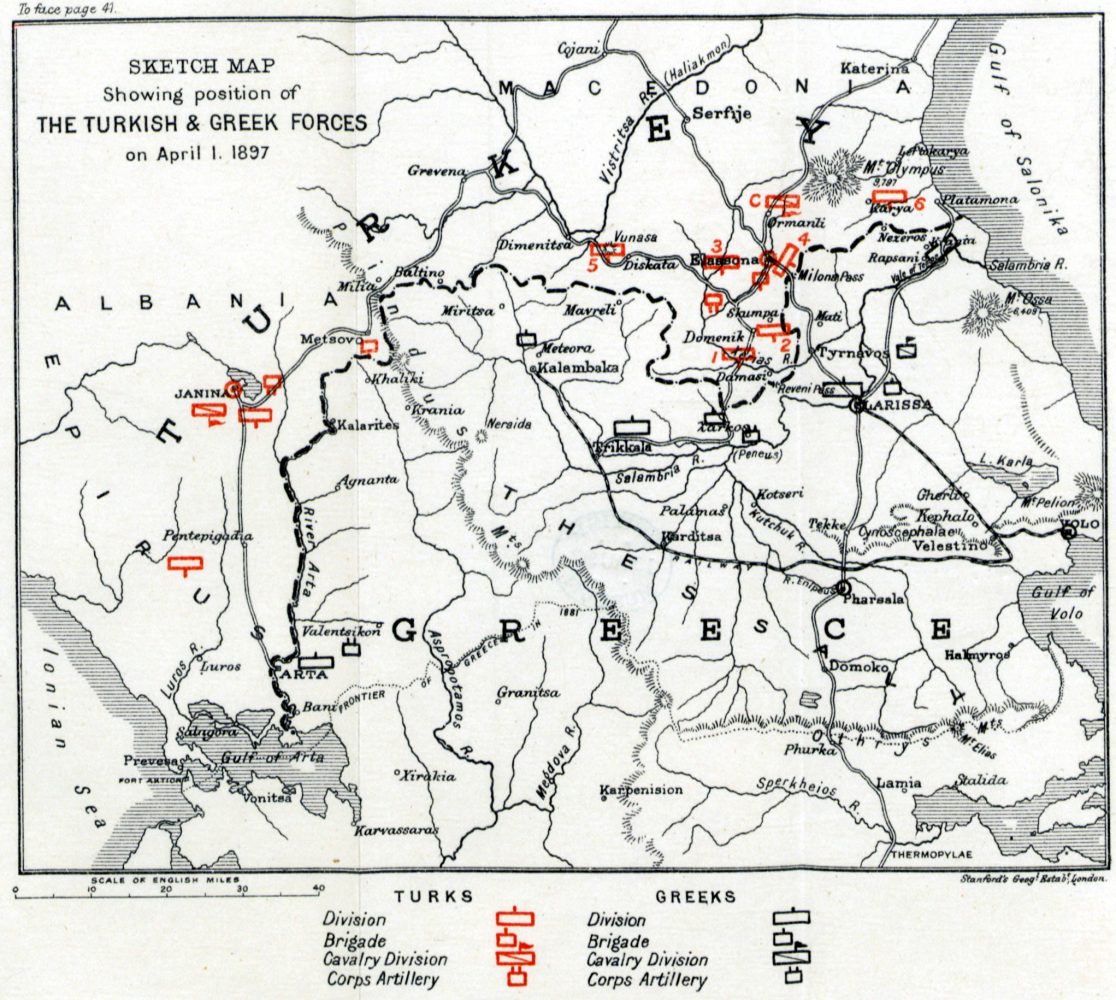

Early in March, 1897, it became clear that the Greek Government intended to provoke a war with Turkey. The dispatch of Colonel Vasscs’s force to Crete, the firing on Turkish transports in Cretan waters, and the mobilizing of troops in Thessaly proved this intention. The Turkish Government re plied by mobilizing the army corps in Macedonia and by increasing the garrison of Janina to a full division. By the end of March fifty thousand Turkish troops were under Edhem Pacha in and around Elassona, close to the Greek frontier.

The Marshal wisely chose this place as his headquarters, for it lies within the angle formed by the sudden trend southward of the Pindus mountain range. Elassona was equally well placed for striking the Greeks if they should invade Macedonia on either the eastern or the western side of the frontier. It was also close to the Melouna Pass, the principal road from Macedonia into Thessaly. The Greeks were collecting their forces at Larissa and Trikkala, and also on the Epirote frontier at Ana.

The chief stimulus to war came from a powerful and wide spread secret society, the Ethnike Hetairi^ (“National Society”). This association formed an imperium in imperio, which for a time almost controlled Greek politics. It embraced within its ranks many members of the Greek Legislature and a large number of army officers. During the three months before the outbreak of war the Ethnike Hetairia was more powerful than the Government. Its secret fiats were irresistible, and the actual filibustering band, whose inroad against Grevena directly caused the war, was armed, equipped, and dispatched into Turkish territory by this dangerous association.

This Ethnike Hetairia was indeed a formidable and mischievous body. It embraced nearly half the young men of Greece. Its leaders and inspirers were ambitious and almost wholly irresponsible. Owing to its influence, the King and the royal family were obliged to give in to the Cretan plot, and to head a dangerous movement, which they could not control. The society issued its edicts, and forthwith arms and agitators were poured into Crete. Another secret edict compelled the King to send Colonel Vassos and his soldiers to Crete. A third edict forced a menacing mobilization on the Thessalian frontier.

The Ethnike Hetairia was active among all the Greek colonies in Asia Minor and in Egypt. It recruited among the young Greek subjects of the Sultan, and hundreds, even thousands of Greek lads and young men sailed from Constantinople, Smyrna, and Alexandria to Greece. This society and the efforts of the Greek Government failed to stir up any trouble among the Greek population in Macedonia, who are neither discontented nor war like. In Epirus there was more movement, but it amounted to very little.

The power of the Ethnike Hetairia waned in proportion as the war was unsuccessful and its policy was proved to be disastrous. So fallen was the Ethnike Hetairia from its high estate that M. Rhallys, at the end of May, made bold to seize all its papers and threaten its officers with prosecution. After this timely act of courage, little was heard of it.

The melting of the snows at the end of March and the clearing of the passes and roads were bound to mark a critical time in the relations of the two countries. Accordingly the armies on both sides were considerably reinforced, and the tension soon became acute.

The line along which the two armies were opposed was more than two hundred miles long. It extended from the Aegean Sea near the Turkish frontier post of Platamona on the east, to the Adriatic on the west — that is, to Arta and Prevesa. The country was for the most part exceedingly wild and broken. Nearly the whole Thessalian frontier line lay along the ridges of the mountain boundary, the Greek and Turkish blockhouses facing each other along the mountain-tops. On the southern part of the Epirote frontier, near Arta, the Turkish territory was more level and exposed. The two chief centers were, on the Turkish side, for Macedonia and Thessaly, Elassona; for Epirus, Janina. On the Greek side, Larissa and Arta were the respective headquarters at the beginning of the war.

The real base of the Turkish army was Saloniki, which had not been connected with Constantinople by railway till the end of 1896. Here the whole military organization and the forwarding of troops and supplies were in the hands of an able and careful officer, Kiazim Pacha. His efforts were well seconded by the Civil Governor, Riza Pacha, Vali of Saloniki. The result was that the great masses of troops, nearly two hundred thousand in all, with the supplies and ammunition, were forwarded to the front without delay and with wonderful precision and order. The railway to Monastir ran fifty miles beyond Saloniki to a small place called Kalaferia, and here the road transport began. Everything had to be carried by baggage-animals or by rough carts from Kalaferia to Elassona, a distance of eighty miles. But Saloniki was the real base.

On the Greek side, Volo was the base. This flourishing seaport, two hundred fifty miles from Athens, is connected by rail with Larissa (thirty- eight miles) and with Pharsalos, Trikkala, and Kalabaka (eighty miles). The junction is at Valestinos, ten miles from Volo, and is therefore a very important strategic point, as the war proved. The command of the sea enabled the Greeks to mobilize their forces with ease and rapidity. All their troops were sent by sea from the Piraeus to Volo, and thence passed forward into Thessaly by the railway. The land road from Athens to the frontier is long and bad.

The proposal of Austria to blockade Volo and the Piraeus early in March, 1897, was therefore most reasonable. It would have prevented Greek mobilization and so have averted the war. It would have been the truest kindness to Greece.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.