This series has six easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: How the Companies Got Their Power.

Introduction

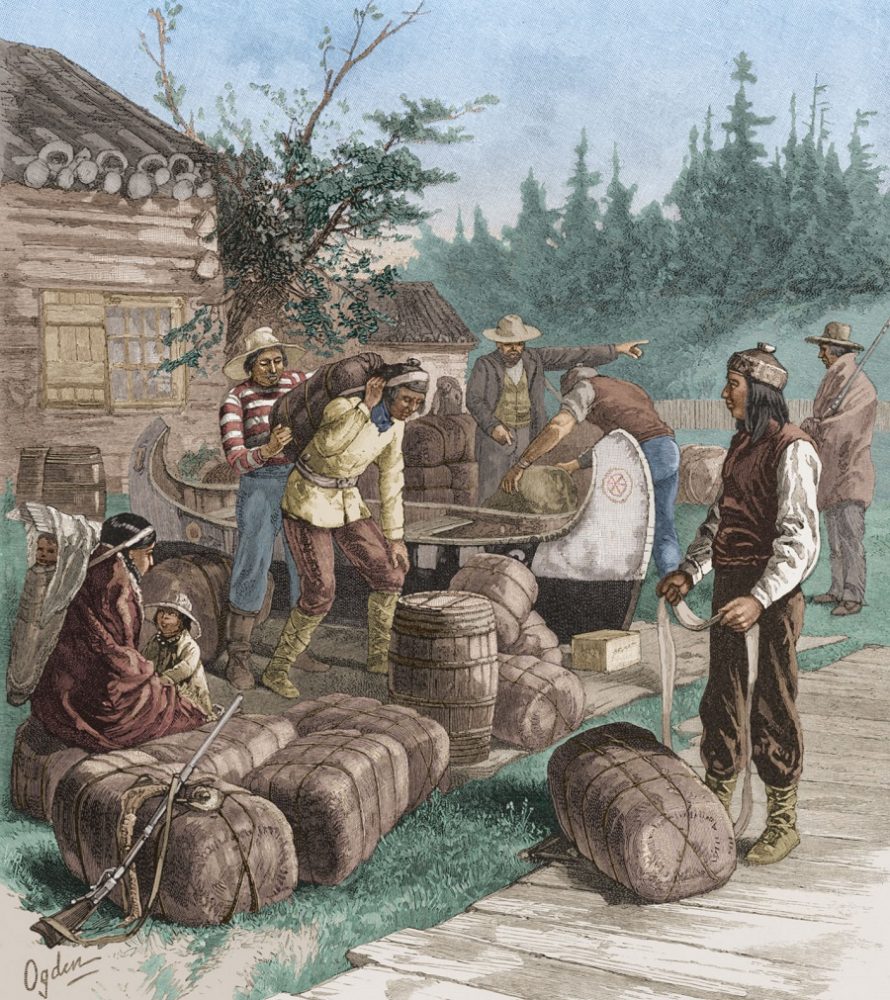

The fur-trade of Canada, once large and lucrative, has diminished by colonization and the opening up of the country by the railways. In its prime, vast was the industry at the great entrepots of the Hudson Bay Company, at the Moose River and York factories, on the shores of the great inland sea discovered by Henry Hudson, as well as at Fort William, on Lake Superior, the headquarters of its chief rival, the Northwest Company. Today the peltry trade is greatly reduced, and what remains is mainly shipped by the railway companies at Montreal, Winnipeg, and Victoria, B. C., instead of by the sailing-vessels that used to come annually to the exporting-posts on Hudson Bay. The value of the season’s catch is estimated at about two and a half million dollars; while its bulk is still large and varied, though consisting chiefly now of beaver, mink, musquash, and marten. In the early days of Canada, the fur-trade was obviously very helpful in opening up the country for settlement and civilization, especially along the great waterways; though that was not to its advantage, nor was it the ostensible purpose of the fur companies, in their trade relations with the Indian and white trappers of the region, or with the French ‘voyageurs and coureurs de boi’. Their interest manifestly lay in keeping the country a vast, silent, and unsettled preserve of game.

Long and keen, as will be seen from the following article, was the rivalry that existed between the two chief fur-trading companies engaged in the industry, though the adventurous life their employees led was fascinating in spite of the loneliness and the isolation from their kin and kind in the far-off and widely scattered posts of the companies. Each at length was the gainer by the amalgamation that ensued in 1821; while the British Government was the gainer, on the expiration of the trading charters, by the purchase and taking over of the joint companies’ rights and privileges in 1869, and their transfer, for the compensation of one million five hundred thousand dollars, to the Canadian Dominion. Nor have the joint companies been much the losers by the transaction, since, besides the money payment, they received a grant of three and a half million acres of land in the fertile belt of the great Canadian Northwest, which, in the altered economic conditions of the region, must be of vast and increasing value in the era of settlement and enormous wheat-raising that has now in great measure displaced the old and profitable fur-trade.

This selection is from The Canadian Northwest: Its History And Its Troubles From The Early Days Of The Fur Trade To The Era Of The Railway And The Settler by G. Mercer Adam published in 1885. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

G. Mercer Adam (1839-1912) was a Canadian author, editor, and publisher.

Time: 1869

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

We should be glad if we could say that the world has out-grown monopolies. One monopoly on this continent, however, it has outgrown. A great fur-trading corporation that had seen ten British sovereigns come and go while it held sway over the territories once ceded to his Serene Highness Rupert, Prince Palatine of the Rhine, yielded up its proprietary interests to the Government of a young and lusty nation. In 1869 the rule over the “Great Lone Land” of the Honorable Company of Merchant Adventurers trading to Hudson Bay ceased, and the Dominion of Canada took over almost its entire interests. With the relinquishment of its rights and privileges, though it stipulated for the retention of some of its trading-posts and a certain portion of land, the company parted with not a few of the factors, trappers, voyageurs, and laborers that had grown gray in its service. It parted with its millions of acres of territory, some of its isolated posts, and their treasuries of fox-skin, marten, mink, muskrat, and otter. It parted with the traditions and associations of centuries of traffic, and all the pretensions that adhere to absolute power in the hands of an old and wealthy corporation and a long-established monopoly. So scattered and distant were the possessions of the company that many moons rose and waned ere the news reached the secluded inmates of its lonely stockaded posts that the great trading company had transferred its interests to the British Government, and from that to the Canadian people. The price of the transfer was a million and a half of dollars.

The cession of the interests of the Hudson Bay Company in the vast tract of country known as Rupert’s Land set at rest the long-vexed question of the right of that corporation to the lord ship of the region known as the Hudson Bay Territories. It set at rest, also, not only the validity of the company’s title to the territory, but the equally delicate question of the area over which the company was supposed to rule. Both questions often disturbed the councils of the company, and at successive periods were the subjects of contemplated Parliamentary inquiry.

Not only was it held that the company, in the course of time, had extended its territorial claims much further than the charter or any sound construction of it would warrant, but the charter itself was repeatedly called in question. In 1670, when the company was founded, it seems clear that the English sovereign, Charles II, had no legal right to the country, for it was then and long afterward the possession of France. By the treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye (1632) the English had resigned to the French Crown all interest in New France. The Treaty of Ryswick (1697), moreover, confirmed French right to the country. Hence Charles’s gift to his cousin, Prince Rupert, and to those associated with him in the organization of the Hudson Bay Company, was gratuitous, if not illegal. The subsequent retransfer of the country to Britain by the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) may be said, however, to have given the company a right to its possessions, a right that was practically confirmed by the Conquest, and by the Treaty of Paris, in 1763. But, conceding this, there arose the other question, namely, to what extent of territory, by the terms of the original charter, was the company entitled? The text of the charter conveys only those lands whose waters drain into Hudson Bay, or, more specifically, “ all the lands and territories upon the countries, coasts, and confines of the seas, etc., that lie within Hudson Straits.” This very materially limited the area of the company’s sway in the Northwest, and nullified its claim over the country that drains into the St. Lawrence, into the Atlantic, the Pacific, and the Arctic oceans. The company, of course, never acknowledged this view of the matter but had its title been tested in a court of law, its territorial assumptions would doubtless have been greatly abridged.

In 1666 two French Huguenots made their way round Lake Superior, ascended the Kaministiquia River, and following the waterway, subsequently known as the Dawson route, reached Winnipeg River and Lake, and probed a route for themselves down the Nelson to the sea discovered by Henry Hudson. In process of time they returned to Quebec, and proceeded to France, where they endeavored to interest capitalists in opening up the fur-bearing regions of Hudson Bay to commerce. But French enterprise was then looking to the East rather than to the West, to the extension of trade in the rich archipelago of the East Indies, rather than to that in the frozen seas of the North. Silks and spices and the diamonds of the Orient were more attractive just then to the Gallic sense than the skins of wild beasts. The two French explorers we have referred to were thus foiled in the attempt to enlist French capital in their enterprise. But one of them, M. de Grosseliez, was not to be balked. He went to England, and there met with the retired student soldier Prince Rupert, whose head was filled with curious schemes of enterprise; and his imagination was readily fired with the story that M. de Grosseliez had to tell.

The result was the forming of the English Hudson Bay Company, and the grant of Charles II over the region in which the company intended to operate. A New England captain connected with the Newfoundland trade was the first to sail to Hudson Bay to further the interests of the new-formed company. Presently a governor was dispatched to establish and take charge of a fort on the Rupert River and one on the Nel son. By the year 1686 the Hudson Bay Company had organized five trading-posts round the shores of James Bay and Hud son Bay. These were known as the Albany, the Moose, the Rupert, the Nelson, and the Severn factories. The right to establish these posts was actively combated by the French, who sent contingents from Quebec, by the Ottawa and by Lake Superior, to harass the English in their possession of them. For several years a keen conflict was maintained between the two races, and the forts successively changed hands as Fortune happened to favor the one or the other. Possession was further varied by the treaties of Ryswick and Utrecht.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.