There was great indignation at headquarters at this escapade of Mahmoud,

Continuing Greco-Turkish War of 1897,

our selection from Battlefields of Thessaly by Sir Ellis Ashmead Bartlett published in 1897. The selection is presented in seven easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Greco-Turkish War of 1897.

Time: 1897

Place: Thessaly and Crete

CC 0 image from Wikipedia.

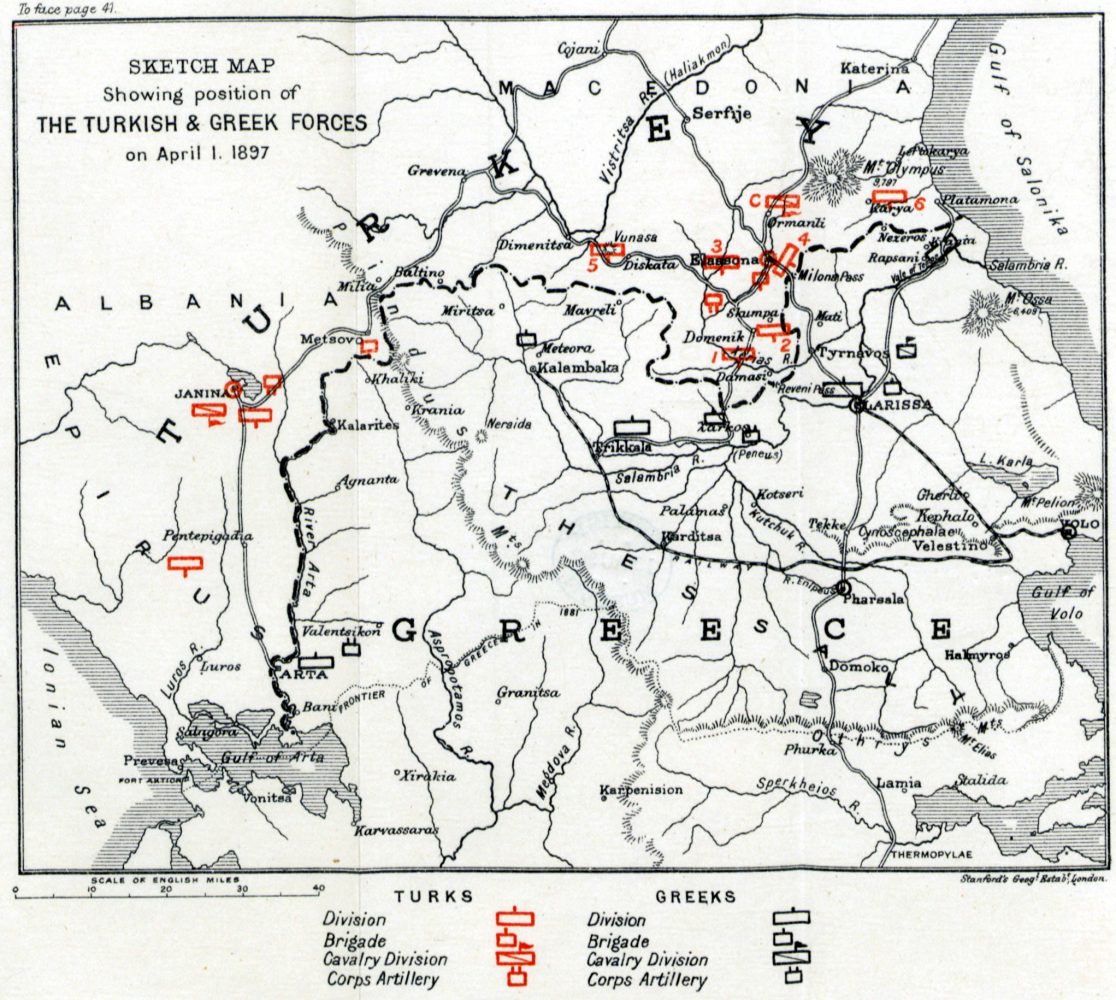

The combat began on April 29th, when Mahmoud Bey undertook a reconnaissance in the direction of Valestinos. Mahmoud had two battalions of Hakki Pacha’s division, a battery of artillery, and six of the ten available squadrons of the cavalry division, amounting to about six hundred sabers. His idea was to turn the Greek left by advancing along the heights of Cynoscephalae on the southwest of Valestinos, and so come down upon that important railway junction from the flank and rear. But Mahmoud seriously miscalculated the strength of Colonel Smolensky’s force, which was estimated at ten thousand, and which I calculated on the field to be at least twelve thousand. There is no doubt that Smolenski received reinforcements on Friday, for we saw the trains steaming into the station, and shortly afterward the Greeks took the offensive with great vigor.

There was little fighting on the 29th. Mahmoud Bey with his two battalions advanced from Gherli southeastward toward Valestinos, and arrived within about two miles of that town on its west. The infantry moved along the ridges of Cynoscephalae, trying to outflank the Greeks at Valestinos; the cavalry explored the level ground below, which was thick with waving corn, and the artillery had a little duel with the Greek guns. Mahmoud asked for reinforcements, and an extra battalion was sent to him.

The next morning the battle was resumed at an early hour. The Turks took the village of Kephalo. Mahmoud Bey then committed an act of extraordinary foolhardiness, which cost the cavalry severely and materially contributed to the reverses of the day. He ordered the Turkish cavalry to charge a Greek entrenchment on the center hill, held by infantry. The order was obeyed with great gallantry. The cavalry rode boldly at the Greek entrenchment, in spite of a heavy fire. Mahmoud himself led. They actually captured one entrenchment, and a Greek officer, who bravely held his ground and fired his revolver with much effect, was cut down by Mahmoud. A second and more formidable entrenchment now confronted the Turkish horse. They suffered from a heavy flanking fire, and were obliged to retire, with a loss of fifty men and nearly half of their horses disabled.

A correspondent with the Greeks thus describes this charge:

QUOTE

“About half-past ten fifteen hundred Circassian horse attempted to dislodge the Greek battery, which had been doing terrible execution among the Turkish infantry, who were attacking the village of Valestinos. The charge was reckless and foolhardy, but a brilliant and memorable sight as the horsemen swept up the slope toward our guns, the long line of glittering sabers flashing in the sunlight. As they approached the battery, puffs of smoke spurted up from the ground in their immediate front, from the Greek infantry lying hidden in front of the guns, and a hail of bullets sped into the mass of advancing cavalry. The horses reared and plunged as their riders pulled them up in dismay, when a brisk fire from the infantry, hurrying from the outskirts of the village of Valestinos on their left flank, immediately decided the course these gallant and reckless horsemen must pursue. They whirled around, and, spreading out fan-shape right and left as they rode, hurriedly retreated from the spur to the position on the plain they had occupied before the charge, the Greek guns harassing their retreat with considerable effect. A loud cheer burst from the Greek infantry and gunners as the horsemen scattered across the valley. General Smolenski and his staff, who had been watching the reckless charge, could not restrain their delight, and joined in the cheer of their men; and the General exclaimed with intense emotion that probably henceforth his soldiers would not regard the terrible Circassian cavalry as such a bogey as they had hitherto imagined it.”

There was great indignation at headquarters at this escapade of Mahmoud, which incapacitated for action the best part of Edhem’s meagre cavalry division. The retreat of the Turkish cavalry was covered by the infantry in and around Kephalo, upon whom the Greeks now pressed forward in great numbers and with loud shouts. A tremendous succession of fusillades was fired by the elated Greeks with little effect. Meanwhile, on the Turkish left, Hakki Pacha had sent forward four battalions and two batteries under Naim Pacha — one of the brigadiers — to occupy Rizomylou, and to press back the Greeks on the far left. These were in force and entrenched at the foot of Pilaf Tepe, and in the fields that sloped upward to Valestinos and the low ridges on the left of that town. We found the fiat-topped belfry-tower of Rizomylou church, sixty feet high, an excellent coign of vantage from which to watch the fight; there we spent the last four hours of Friday’s battle. Naim himself was on the flat ground, midway between Pilaf Tep6 and Rizomylou. He had with him two batteries of artillery, which did little during the 30th, and two squadrons of cavalry that moved about in the cornfields between Rizomylou and the middle of the wood. Parts of two infantry battalions were within Rizomylou and in front of it ; part were advancing through the wood. Two more were clearing out the Greek intrenchments at the foot of Pelion. Later these tried to storm the slopes of Pilaf Tepe — an exploit almost as difficult and reckless at Mahmoud’s cavalry charge.

About noon we rode up to Naim Pacha the brigadier and found him watching with equanimity the progress of the battle that was raging furiously both on the left and the far right. There seemed to be no connection between the two separate engagements that were then at their height : the one at the foot of Pelion a mile and a half to the southeast ; the other around Kephalo, two miles and a half to the southwest. Nothing was occurring in the Turkish center, which extended only about half a mile south of Rizomylou. The two battalions on the left front began swarming up the steep hillsides like ants, under a terrific fire from the Greeks, who had a series of entrenchments on the slopes.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.