Most of the contracts between seignior and censitaire had been agreed upon in good faith by men who knew as much of the Coutume de Paris as of the Capitularies of Charlemagne, and their conditions had remained in force unchallenged for generations.

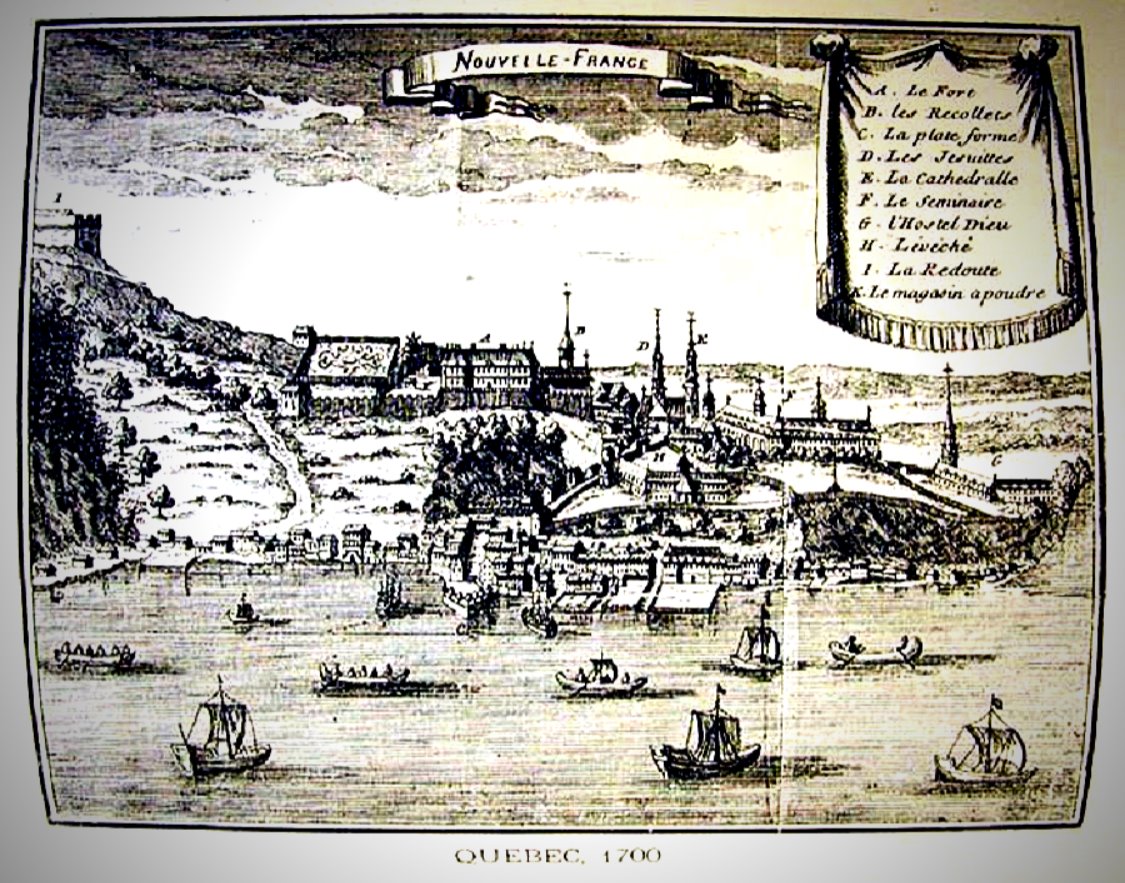

CC BY-SA 1.0 image from Wikipedia.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in The Old Regime In Canada. Continuing chapter 15

A more considerable but a very uncertain source of income to the seignior were the lods et ventes, or mutation fines. The land of the censitaire passed freely to his heirs; but if he sold it, a twelfth part of the purchase-money must be paid to the seignior. The seignior, on his part, was equally liable to pay a mutation fine to his feudal superior if he sold his seigniory; and for him the amount was larger, being a quint, or a fifth of the price received, of which, however, the greater part was deducted for immediate payment. This heavy charge, constituting, as it did, a tax on all improvements, was a principal cause of the abolition of the feudal tenure in 1854.

The obligation of clearing his land and living on it was laid on seignior and censitaire alike; but the latter was under a variety of other obligations to the former, partly imposed by custom and partly established by agreement when the grant was made. To grind his grain at the seignior’s mill, bake his bread in the seignior’s oven, work for him one or more days in the year, and give him one fish in every eleven, for the privilege of fishing in the river before his farm; these were the most annoying of the conditions to which the censitaire was liable. Few of them were enforced with much regularity. That of baking in the seignior’s oven was rarely carried into effect, though occasionally used for purposes of extortion. It is here that the royal government appears in its true character, so far as concerns its relations with Canada, that of a well-meaning despotism. It continually intervened between censitaire and seignior, on the principle that “as his Majesty gives the land for nothing, he can make what conditions he pleases, and change them when he pleases.” [1] These interventions were usually favorable to the censitaire. On one occasion an intendant reported to the minister, that in his opinion all rents ought to be reduced to one sou and one live capon for every arpent of front, equal in most cases to forty superficial arpents. [3] Everything, he remarks, ought to be brought down to the level of the first grants “made in days of innocence,” a happy period which he does not attempt to define. The minister replies that the diversity of the rent is, in fact, vexatious, and that, for his part, he is disposed to abolish it altogether. [3] Neither he nor the intendant gives the slightest hint of any compensation to the seignior. Though these radical measures were not executed, many changes were decreed from time to time in the relations between seignior and censitaire, sometimes as a simple act of sovereign power, and sometimes on the ground that the grants had been made with conditions not recognized by the Coutume de Paris. This was the code of law assigned to Canada; but most of the contracts between seignior and censitaire had been agreed upon in good faith by men who knew as much of the Coutume de Paris as of the Capitularies of Charlemagne, and their conditions had remained in force unchallenged for generations. These interventions of government sometimes contradicted each other, and often proved a dead letter. They are more or less active through the whole period of the French rule.

[1: This doctrine is laid down in a letter of the Marquis de Beauharnois, governor, to the minister, 1734.]

[2: Lettre de Raudot, père, au Ministre, 10 Nov., 1707.]

[3: Lettre de Ponchartrain à Raudot, père, 13 Juin, 1708.]

The seignior had judicial powers, which, however, were carefully curbed and controlled. His jurisdiction, when exercised at all, extended in most cases only to trivial causes. He very rarely had a prison, and seems never to have abused it. The dignity of a seigniorial gallows with high justice or jurisdiction over heinous offences was granted only in three or four instances.

[Baronies and comtés were empowered to set up gallows and pillories, to which the arms of the owner were affixed. See, for example, the edict creating the Barony des Islets.]

Four arpents in front by forty in depth were the ordinary dimensions of a grant en censive. These ribbons of land, nearly a mile and a half long, with one end on the river and the other on the uplands behind, usually combined the advantages of meadows for cultivation, and forests for timber and firewood. So long as the censitaire brought in on St. Martin’s day his yearly capons and his yearly handful of copper, his title against the seignior was perfect. There are farms in Canada which have passed from father to son for two hundred years. The condition of the cultivator was incomparably better than that of the French peasant, crushed by taxes, and oppressed by feudal burdens far heavier than those of Canada. In fact, the Canadian settler scorned the name of peasant, and then, as now, was always called the habitant. The government held him in wardship, watched over him, interfered with him, but did not oppress him or allow others to oppress him. Canada was not governed to the profit of a class, and if the king wished to create a Canadian noblesse he took care that it should not bear hard on the country.

[On the seigniorial tenure, I have examined the whole of the mass of papers printed at the time when the question of its abolition was under discussion. A great deal of legal research and learning was then devoted to the subject. The argument of Mr. Dunkin in behalf of the seigniors, and the observations of Judge Lafontaine, are especially instructive, as is also the collected correspondence of the governors and intendants with the central government on matters relating to the seigniorial system.]

Under a genuine feudalism, the ownership of land conferred nobility; but all this was changed. The king and not the soil was now the parent of honor. France swarmed with landless nobles, while roturier land-holders grew daily more numerous. In Canada half the seigniories were in roturier or plebeian hands, and in course of time some of them came into possession of persons on very humble degrees of the social scale. A seigniory could be bought and sold, and a trader or a thrifty habitant might, and often did become the buyer. [4] If the Canadian noble was always a seignior, it is far from being true that the Canadian seignior was always a noble.

[4: In 1712, the engineer Catalogne made a very long and elaborate report on the condition of Canada, with a full account of all the seigniorial estates. Of ninety-one seigniories, fiefs, and baronies, described by him, ten belonged to merchants, twelve to husbandmen, and two to masters of small river craft. The rest belonged to religious corporations, members of the council, judges, officials of the Crown, widows, and discharged officers or their sons]

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In France, it will be remembered, nobility did not in itself imply a title. Besides its titled leaders, it had its rank and file, numerous enough to form a considerable army. Under the later Bourbons, the penniless young nobles were, in fact, enrolled into regiments, turbulent, difficult to control, obeying officers of high rank, but scorning all others, and conspicuous by a fiery and impetuous valor which on more than one occasion turned the tide of victory. The gentilhomme, or untitled noble, had a distinctive character of his own, gallant, punctilious, vain; skilled in social and sometimes in literary and artistic accomplishments, but usually ignorant of most things except the handling of his rapier. Yet there were striking exceptions; and to say of him, as has been said, that “he knew nothing but how to get himself killed,” is hardly just to a body which has produced some of the best writers and thinkers of France.

Sometimes the origin of his nobility was lost in the mists of time; sometimes he owed it to a patent from the king. In either case, the line of demarcation between him and the classes below him was perfectly distinct; and in this lies an essential difference between the French noblesse and the English gentry, a class not separated from others by a definite barrier. The French noblesse, unlike the English gentry, constituted a caste.

The gentilhomme had no vocation for emigrating. He liked the army and he liked the court. If he could not be of it, it was something to live in its shadow. The life of a backwoods settler had no charm for him. He was not used to labor; and he could not trade, at least in retail, without becoming liable to forfeit his nobility. When Talon came to Canada, there were but four noble families in the colony. [5] Young nobles in abundance came out with Tracy; but they went home with him. Where, then, should be found the material of a Canadian noblesse? First, in the regiment of Carignan, of which most of the officers were gentilshommes; secondly, in the issue of patents of nobility to a few of the more prominent colonists. Tracy asked for four such patents; Talon asked for five more; [6] and such requests were repeated at intervals by succeeding governors and intendants, in behalf of those who had gained their favor by merit or otherwise. Money smoothed the path.

[5: Talon, Mémoire sur l’Etat présent du Canada, 1667. The families of Repentigny, Tilly, Poterie, and Aillebout appear to be meant.]

[6: Tracy’s request was in behalf of Bourdon, Boucher, Auteuil, and Juchereau. Talon’s was in behalf of Godefroy, Le Moyne, Denis, Amiot, and Couillard to advancement, so far had noblesse already fallen from its old estate.]

Thus Jacques Le Ber, the merchant, who had long kept a shop at Montreal, got himself made a gentleman for six thousand livres.

[Faillon, Vie de Mademoiselle Le Ber, 325.]

All Canada soon became infatuated with noblesse; and country and town, merchant and seignior, vied with each other for the quality of gentilhomme. If they could not get it, they often pretended to have it, and aped its ways with the zeal of Monsieur Jourdain himself. “Everybody here,” writes the intendant Meules, “calls himself Esquire, and ends with thinking himself a gentleman.” Successive intendants repeat this complaint. The case was worst with roturiers who had acquired seigniories. Thus Noel Langlois was a good carpenter till he became owner of a seigniory, on which he grew lazy and affected to play the gentleman. The real gentilshommes, as well as the spurious, had their full share of official stricture. The governor Denonville speaks of them thus: “Several of them have come out this year with their wives, who are very much cast down; but they play the fine lady, nevertheless. I had much rather see good peasants; it would be a pleasure to me to give aid to such, knowing, as I should, that within two years their families would have the means of living at ease; for it is certain that a peasant who can and will work is well off in this country, while our nobles with nothing to do can never be any thing but beggars. Still they ought not to be driven off or abandoned. The question is how to maintain them.”

[Lettre de Denonville au Ministre, 10 Nov., 1686.]

The intendant Duchesneau writes to the same effect: “Many of our gentilshommes, officers, and other owners of seigniories, lead what in France is called the life of a country gentleman, and spend most of their time in hunting and fishing. As their requirements in food and clothing are greater than those of the simple habitants, and as they do not devote themselves to improving their land, they mix themselves up in trade, run in debt on all hands, incite their young habitants to range the woods, and send their own children there to trade for furs in the Indian villages and in the depths of the forest, in spite of the prohibition of his Majesty. Yet, with all this, they are in miserable poverty.” [7] Their condition, indeed, was often deplorable. “It is pitiful,” says the intendant Champigny, “to see their children, of which they have great numbers, passing all summer with nothing on them but a shirt, and their wives and daughters working in the fields.” [8] In another letter he asks aid from the king for Repentigny with his thirteen children, and for Tilly with his fifteen. “We must give them some corn at once,” he says, “or they will starve.” [9] These were two of the original four noble families of Canada. The family of Aillebout, another of the four, is described as equally destitute. “Pride and sloth,” says the same intendant, “are the great faults of the people of Canada, and especially of the nobles and those who pretend to be such. I pray you grant no more letters of nobility, unless you want to multiply beggars.” [10] The governor Denonville is still more emphatic: “Above all things, monseigneur, permit me to say that the nobles of this new country are everything that is most beggarly, and that to increase their number is to increase the number of do-nothings. A new country requires hard workers, who will handle the axe and mattock. The sons of our councilors are no more industrious than the nobles; and their only resource is to take to the woods, trade a little with the Indians, and, for the most part, fall into the disorders of which I have had the honor to inform you. I shall use all possible means to induce them to engage in regular commerce; but as our nobles and councillors are all very poor and weighed down with debt, they could not get credit for a single crown piece.” [11] “Two days ago,” he writes in another letter, “Monsieur de Saint-Ours, a gentleman of Dauphiny, came to me to ask leave to go back to France in search of bread. He says that he will put his ten children into the charge of any who will give them a living, and that he himself will go into the army again. His wife and he are in despair; and yet they do what they can. I have seen two of his girls reaping grain and holding the plough. Other families are in the same condition. They come to me with tears in their eyes. All our married officers are beggars; and I entreat you to send them aid. There is need that the king should provide support for their children, or else they will be tempted to go over to the English.” [12] Again he writes that the sons of the councilor D’Amours have been arrested as coureurs de bois, or outlaws in the bush; and that if the minister does not do something to help them, there is danger that all the sons of the noblesse, real or pretended, will turn bandits, since they have no other means of living.

[7: Lettre de Duchesneau au Ministre, 10 Nov., 1679.]

[8: Lettre de Champigny au Ministre, 26 Août, 1687.]

[9: Ibid., 6 Nov., 1687.]

[10: Mémoire instructif sur le Canada, joint a la lettre de M. de Champigny du 10 May, 1691.]

[11: Lettre de Denonville au Ministre, 13 Nov., 1685.]

[12: Lettre de Denonville au Ministre, 10 Nov., 1686. (Condensed in the translation.)]

– The Old Regime In Canada, Chapter 15 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Introduction.

If, at times, it may seem that range has been allowed to fancy, it is so in appearance only; since the minutest details of narrative or description rest on authentic documents or on personal observation.

Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than a research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. Such facts may be detailed with the most minute exactness, and yet the narrative, taken as a whole, may be unmeaning or untrue. The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time. He must study events in their bearings near and remote; in the character, habits, and manners of those who took part in them, he must himself be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.

With respect to that special research which, if inadequate, is still in the most emphatic sense indispensable, it has been the writer’s aim to exhaust the existing material of every subject treated. While it would be folly to claim success in such an attempt, he has reason to hope that, so far at least as relates to the present volume, nothing of much importance has escaped him. With respect to the general preparation just alluded to, he has long been too fond of his theme to neglect any means within his reach of making his conception of it distinct and true.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

Here is a Kindle version: Complete Works for just $2.

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle.

- History and Culture of the Mississippi River.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.