The moment after Sir Robert Peel succeeded in passing his great measure of free trade he himself fell from power.

Continuing Corn Laws Repealed in England,

our selection from Epoch of Reform by Justin Mccarthy published in 1892. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Corn Laws Repealed in England.

Time: 1846

Place: England

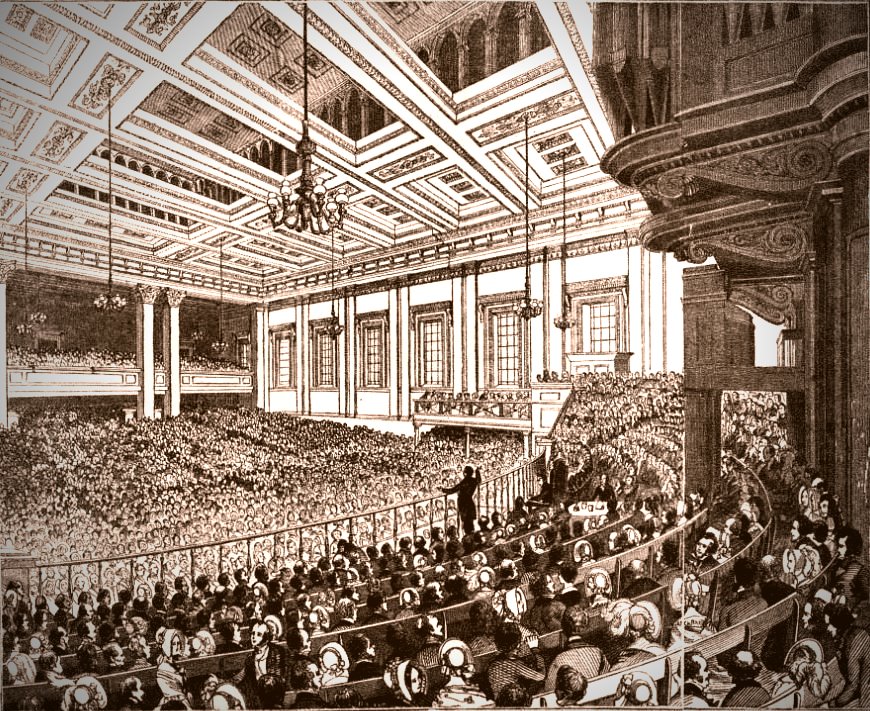

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Parliament met on January 22, 1846. The “speech from the throne,” delivered by the Queen in person, recommended the legislature to take into consideration the necessity of still further applying the principle on which it had formerly acted, when measures were presented “to extend commerce and to stimulate domestic skill and industry, by the repeal of prohibitive and the relaxation of protective duties.” In the debate on the “address” Sir Robert Peel rose, after the mover and seconder had spoken and the question had been put from the Chair, and at once proceeded to explain the policy which he intended to adopt. His speech was long and labored, and somewhat wearied the audience by the elaborate manner in which he explained how his opinions had been brought into gradual change with regard to free trade and protection. He made it, however, perfectly clear that he was now a convert to Cobden’s opinions, and that he intended to introduce some measure which should practically amount to the abolition of protection.

It was in this debate, and immediately after Peel had spoken, that Benjamin Disraeli made his first great impression on Parliament. He had been in the House for many years, and had made many attempts, had sometimes been laughed at, had sometimes been disliked, and occasionally for a moment admired. But it was when he rose immediately after Sir Robert Peel, and denounced Peel as one who had betrayed his party and his principles, that he made the first deep impression on the House of Commons, and came to be considered as a serious and influential Parliamentary personage. “I am not one of the converts,” Disraeli said, “I am perhaps a member of a fallen party.” A new Protection party was formed almost immediately under the leadership of George Lord Bentinck, a man of great energy and tenacity of purpose, who had hitherto spent his life almost altogether on the turf, who had had almost no previous preparation for leadership or even for debate, but who certainly, when he did accept the responsible position offered to him, showed a considerable capacity for leadership and an unwearying attention to his duties.

On January 27th Sir Robert Peel explained his financial policy. His intention was to abandon the sliding scale altogether, to impose for the present a duty of ten shillings a quarter on corn when the price of it was under forty-eight shillings a quarter, to reduce that duty by one shilling for every shilling of rise in price until it reached fifty-three shillings a quarter, when the duty should fall to four shillings. This, however, was to be only a temporary arrangement. It was to last but three years, and at the end of that time protective duties on grain were to be wholly abandoned. We need not go at any length into the history of the long debates on Peel’s propositions. The discussion of one amendment, which was in substance a motion to reject the scheme altogether, lasted for twelve nights. The third reading of the bill passed the House of Commons on May 15th, by a majority of ninety-eight.

The bill went up at once to the House of Lords, and at the urgent pressure of the Duke of Wellington was carried through that House without any serious opposition. The Duke made no secret of his own opinions. He assured many of his brother peers that he disliked the measure just as much as anyone could do, but he insisted that they had all better vote for it nevertheless. Sir Robert Peel had triumphed, but he found himself deserted by a large and influential section of the party he once had led. Most of the great landowners and country gentlemen of the Conservative party abandoned him. Some of them felt the bitterest resentment toward him. They believed he had betrayed them, although nothing could be more clear than that for years he had distinctly been making it known to the House that his principles inclined him toward free trade, and thereby leaving it to be understood that, if opportunity or emergency should compel him, he would be glad to declare himself a Free Trader, even in the matter of grain.

Strange to say, the day when the bill was read in the House of Lords for the third time saw the fall of Peel’s Ministry. The fall was due to the state of Ireland. The Government had been bringing in a coercion bill for Ireland. It was introduced while the Corn Bill was yet passing through the House of Commons. The situation was critical. All the Irish followers of Daniel O’Connell would be sure to oppose the Coercion Bill. The Liberal party, at least when out of office, had usually made it their principle to oppose coercion bills if they were not attended with some promises of legislative reform. The English Radical members, led by Cobden and Bright, were certain to oppose coercion. If the Protectionists should join with these other opponents of the Coercion Bill the fate of the measure was assured, and with it the fate of the Government. This was exactly what happened. Eighty Protectionists followed Lord George Bentinck into the lobby against the bill, in combination with the Free Traders, the Whigs, and the Irish Catholic and national members. The division took place on the second reading of the bill on Thursday, June 25th, and there was a majority of seventy-three against the Ministry.

The moment after Sir Robert Peel succeeded in passing his great measure of free trade he himself fell from power. His political epitaph, perhaps, could not be better written than in the words with which he closed the speech that just preceded his fall: “It may be that I shall leave a name sometimes remembered with expressions of good-will in those places which are the abode of men whose lot it is to labor and to earn their daily bread by the sweat of their brow — a name remembered with expressions of good-will when they shall recreate their exhausted strength with abundant and untaxed food, the sweeter because it is no longer leavened with a sense of injustice.”

With the fall of the principle of the protection in corn may be said to have practically fallen the principle of protection in that country altogether. That principle was a little complicated in regard to the sugar duties and to the navigation laws. The sugar produced in the West Indian colonies was allowed to enter that country at rates of duty much lower than those imposed upon the sugar grown in foreign lands. The abolition of slavery in the colonies had made labor there somewhat costly and difficult to obtain continuously, and the impression was that if the duties on foreign sugar were reduced it would tend to enable those countries which still maintained the slave trade to compete at great advantage with the sugar grown in the colonies by that free labor to establish which England had but just paid so large a pecuniary fine. Therefore the question of free trade became involved with that of free labor; at least, so it seemed to the eyes of many a man who was not inclined to support the protective principle in itself. When it was put to him, whether he was willing to push the free-trade principle so far as to allow countries growing sugar by slave labor to drive our free-grown sugar out of the market, he was often inclined to give way before this mode of putting the question, and to imagine that there really was a collision between free trade and free labor. Therefore a certain sentimental plea came in to aid the Protectionists in regard to the sugar duties.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.