This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Origin of the Corn Laws.

Introduction

The Corn Laws were the most prominent of England’s system of protective tariffs that Parliament had established after the fall of Napoleon. The so-called “corn laws” affected the food. These laws affected mostly the poor. With the prices of this most basic of human needs kept artificially high, public displeasure grew. This is what happened.

This selection is from Epoch of Reform by Justin Mccarthy published in 1892. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Justin Mccarthy (1830-1912) was an Irish nationalist and Liberal historian, novelist and politician.

Time: 1846

Place: England

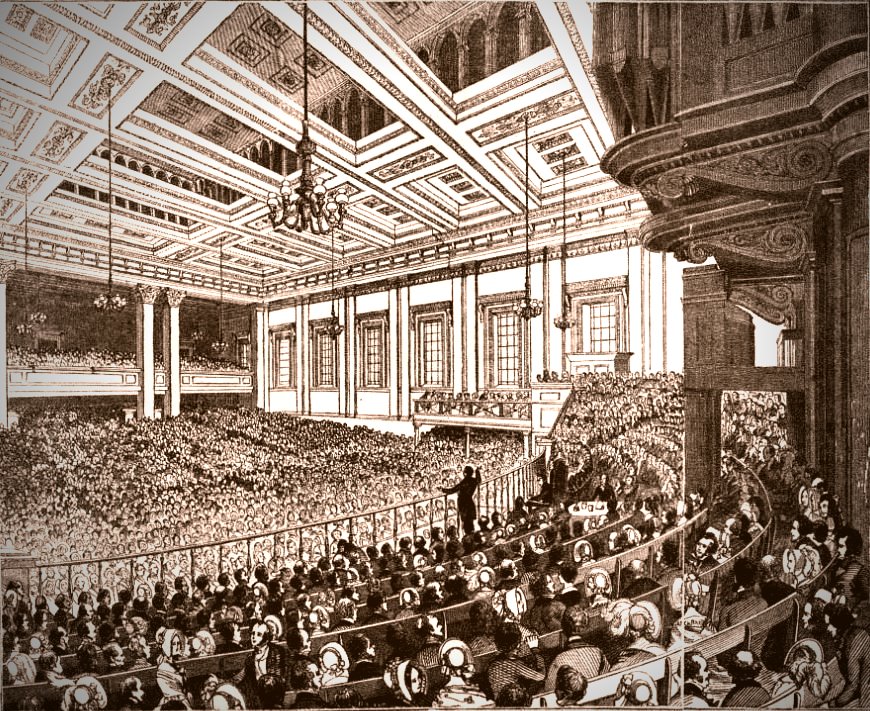

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In 1815 the celebrated Corn Law was passed, which was itself molded on the Corn Law of 1670. By the Act of 1815 wheat might be exported upon a payment of one shilling per quarter customs duty, but the importation of foreign grain was practically prohibited until the price of wheat in England had reached eighty shillings a quarter, that is to say, until a certain price had been secured for the grower of grain at the expense of all the consumers in this country. It was not permitted to Englishmen to obtain their supplies from any foreign land, unless on conditions that suited the English corn-grower’s pocket.

We may perhaps make this principle a little more clear, if it be necessary, by illustrating its working on a small scale and within narrow limits. In a particular street in London, let us say, a law is passed declaring that no one must buy a loaf of bread out of that street, or even round the corner, until the price of bread has risen so high in the street itself as to secure to its two or three bakers a certain enormous scale of profit on their loaves. When the price of bread has been forced up so high as to pass this scale of profit, then it would be permissible for those who stood in need of bread to go round the corner and buy their loaves of the baker in the next street; but the moment that their continuing to do this caused the price of the baker’s bread in their own street to fall below the prescribed limit, they must instantly take to buying bread within their own bounds and of their own bakers again. This is a fair illustration of the principle on which the corn laws were molded. The Corn Law of 1815 was passed in order to enable the landowners and farmers to recover from the depression caused by the long era of foreign war. It was “rushed through” Parliament, if we may use an American expression; petitions of the most urgent nature poured in against it from all the commercial and manufacturing classes, and in vain. Popular disturbances broke out in many places. The poor everywhere saw the bread of their family threatened, saw the food of their children almost taken out of their mouths, and they naturally broke into wild extremes of anger. In London there were serious riots, and the houses of some of the most prominent supporters of the bill were attacked. The incendiary went to work in many parts of the country. At that time it was still the way in England, as it is now in Russia and other countries, for popular indignation to express itself in the frequent incendiary fire. At one place near London a riot lasted for two days and nights; the soldiers had to be called out to put it down, and five men were hanged for taking part in it.

After the passing of the Corn Law of 1815, and when it had worked for some time, there were sliding-scale acts introduced, which established a varying system of duty, so that when the price of home-grown grain rose above a certain figure, the duty on imported wheat was to sink in proportion. The principle of all these measures was the same. How, it may be asked, could any sane legislator adopt such measures? As well might it be asked, How can any civilized nation still, as some still do, believe in such a principle? The truth is that the principle is one which has a strong fascination for most persons, the charm of which it is difficult for any class in its turn wholly to shake off. The idea is that if our typical baker be paid more than the market price for a loaf, he will be able in turn to pay more to the butcher than the fair price for his beef; the butcher thus benefited will be enabled to deal on more liberal terms with the tailor; the tailor so favored by legislation will be able in his turn to order a better kind of beer from the publican and pay a higher price for it. Thus, by some extraordinary process, everybody pays too much for everything, and nevertheless all are enriched in turn. The absurdity of this is easily kept out of sight where the protective duties affect a number of varying and complicated interests, manufacturing, commercial, and productive.

In the United States, for example, where the manufacturers are benefited in one place and the producers are benefited in another, and where the country always produces food abundant to supply its own wants, men are not brought so directly face to face with the fallacy of the principle as they were in England at the time of the Anti-Corn Law League. In America “protection” affects manufacturers for the most part, and there is no such popular craving for cheap manufactures as to bring the protective principle into collision with the daily wants of the people. But in England, during the reign of the Corn Law, the food which the people put into their mouths was the article mainly taxed, and made cruelly costly by the working of protection.

Nevertheless, the country put up with this system down to the close of the year 1836. At that time there was a stagnation of trade and a general depression of business. Severe poverty prevailed in many districts. Inevitably, therefore, the question arose in the minds of most men, in distressed or depressed places, whether it could be a good thing for the country in general to have the price of bread kept high by factitious means when wages had sunk and work become scarce. An Anti-Corn-Law association was formed in London, It began pretentiously enough, but it brought about no result. London is not a place where popular agitation finds a fitting center. In 1838, however, Bolton, in Lancashire, suffered from a serious commercial crisis. Three-fifths of its manufacturing activity became paralyzed at once. Many houses of business were actually closed and abandoned, and thousands of workmen were left without the means of life. Lancashire suddenly roused itself into the resolve to agitate against the corn laws, and Manchester became the headquarters of the movement which afterward accomplished so much.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.