Small as the Polish army was, its maintenance was too great an effort for the resources of the kingdom.

Continuing Poland’s Downfall,

our selection from History of Europe by Sir Archibald Alison published in 1854. The selection is presented in three easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Poland’s Downfall.

Time: 1794

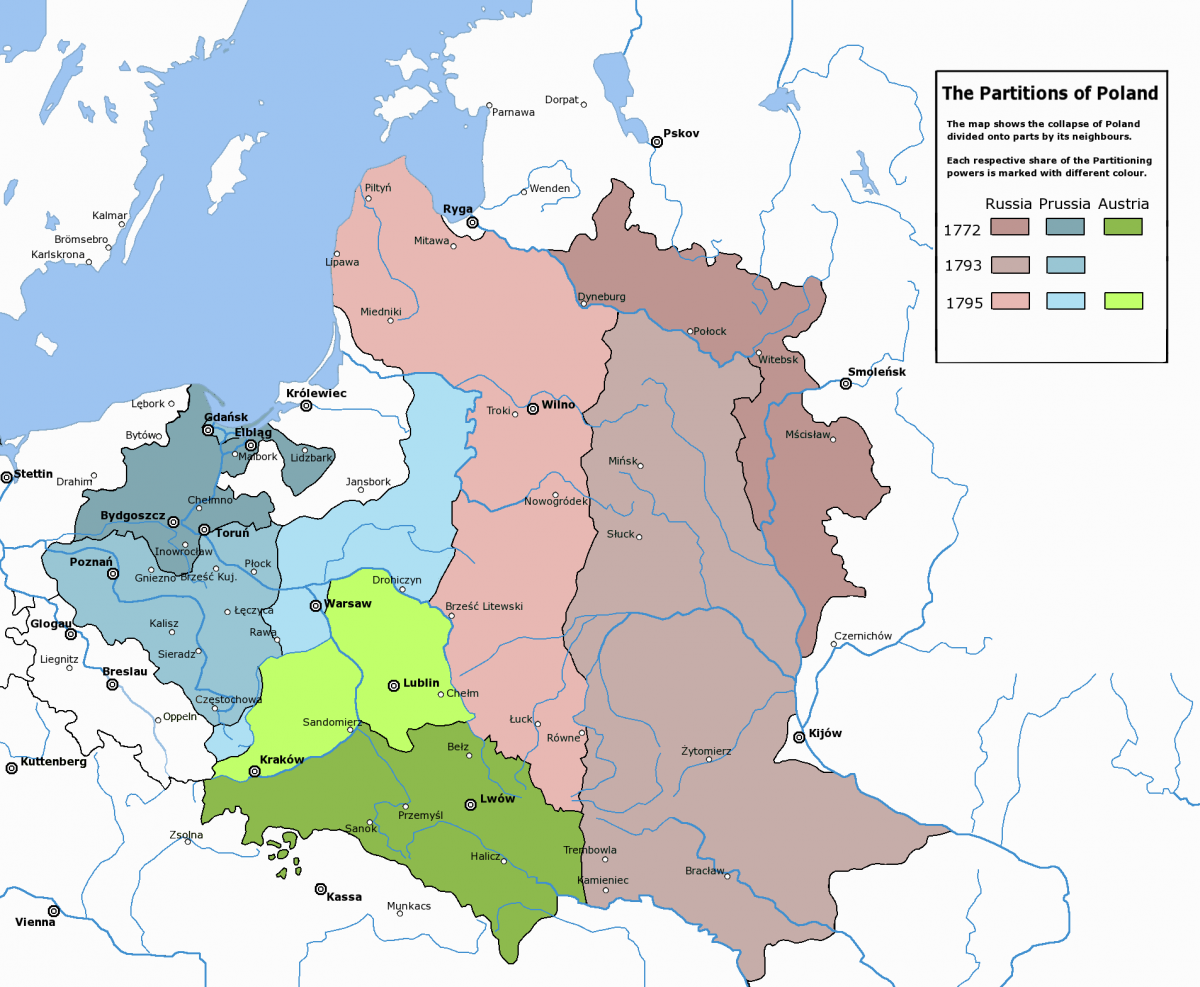

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

One of the most embarrassing circumstances in the situation of the Russians was the presence of above sixteen thousand Poles in their ranks, who were known to sympathize strongly with these heroic efforts of their fellow-citizens. Orders were immediately dispatched to Suvaroff to assemble a corps and disarm the Polish troops scattered in Podolia before they could unite in any common measures for their defense. By the energy and activity of this great commander, the Poles were disarmed brigade after brigade, and above twelve thousand men reduced to a state of inaction without much difficulty — a most important operation, not only by destroying the nucleus of a powerful army, but by stifling the commencement of the insurrection in Volhynia and Podolia. How different might have been the fate of Poland and Europe had they been enabled to join the ranks of their countrymen!

Kosciuszko and his countrymen did everything that courage or energy could suggest to put on foot a formidable force to resist their adversaries; a provisional government was established and in a short time a force of forty thousand men was raised. But this force, though highly honorable to the patriotism of the Poles, was inconsiderable when compared with the vast armies which Russia and Prussia could bring up for their subjugation. Small as the army was, its maintenance was too great an effort for the resources of the kingdom, which, torn by intestine factions, without commerce, harbors, or manufactures; having no national credit, and no industrious class of citizens but the Jews, now felt the fatal effects of its long career of democratic anarchy. The population of the country, composed entirely of unruly gentlemen and ignorant serfs, was totally unable at that time to furnish those numerous supplies of intelligent officers which are requisite for the formation of an efficient military force; while the nobility, however formidable on horseback in the Hungarian or Turkish wars, were less to be relied on in a contest with regular troops, where infantry and artillery constituted the great strength of the army, and courage was unavailing without the aid of science and military discipline.

The central position of Poland, in the midst of its enemies, would have afforded great military advantages, had its inhabitants possessed a force capable of turning it to account; that is, if they had had, like Frederick the Great in the Seven Years’ War, a hundred fifty thousand regular troops — which the population of the country could easily have maintained — and a few well-fortified towns, to arrest the enemy in one quarter, while the bulk of the national force was precipitated upon them in another. The glorious stand made by the nation in 1831, with only thirty thousand regular soldiers at the commencement of the insurrection, and no fortifications but those of Warsaw and Modlin, proves what immense advantages this central position affords, and what opportunities it offers to military genius like that of Skrynecki to inflict the most severe wounds even on a superior and well-conducted antagonist. But all these advantages were wanting to Kosciuszko; and it augments our admiration of his talents, and of the heroism of his countrymen, that with such inconsiderable means they made so honorable a stand for their national independence.

No sooner was the King of Prussia informed of the revolution at Warsaw than he moved forward at the head of thirty thousand men to besiege that city; while Suvaroff, with forty thousand veterans, was preparing to enter the southeastern parts of the kingdom. Aware of the necessity of striking a blow before the enemy’s forces were united, Kosciuszko advanced with twelve thousand men to attack the Russian General, Denisoff; but, upon approaching his corps, he discovered that it had united to the army commanded by the King in person. Unable to face such superior forces, he immediately retired, but was attacked next morning at daybreak near Sekoczyre by the allies, and after a gallant resistance his army was routed, and Cracow fell into the hands of the conquerors. This check was the more severely felt, as about the same time General Zayonscheck was defeated at Chelne and obliged to recross the Vistula, leaving the whole country on the right bank of that river in the hands of the Russians.

These disasters produced a great impression at Warsaw; the people as usual ascribed them to treachery, and insisted that the leaders should be brought to punishment; and although the chiefs escaped, several persons in an inferior situation were arrested and thrown into prison. Apprehensive of some subterfuge if the accused were regularly brought to trial, the burghers assembled in tumultuous bodies, forced the prisons, erected scaffolds in the streets, and after the manner of the assassins of September 2nd, put above twelve persons to death with their own hands. These excesses affected with the most profound grief the pure heart of Kosciuszko; he flew to the capital, restored order, and delivered over to punishment the leaders of the revolt. But the resources of the country were evidently unequal to the struggle; the paper money, which had been issued in their extremity, was at a frightful discount; and the sacrifices required of the nation were, on that account, the more severely felt, so that hardly a hope of ultimate success remained.

The combined Russian and Prussian armies, about thirty-five thousand strong, now advanced against the capital, where Kosciuszko occupied an intrenched camp with twenty-five thousand men. During the whole of July and August the besiegers were engaged in fruitless attempts to drive the Poles into the city; and at length a great convoy, with artillery and stores for a regular siege, which was ascending the Vistula, having been captured by a gentleman named Minewsky at the head of a body of peasants, the King of Prussia raised the siege, leaving a portion of his sick and stores in the hands of the patriots. After this success the insurrection spread immensely and the Poles mustered nearly eighty thousand men under arms. But they were scattered over too extensive a line of country in order to make head against their numerous enemies — a policy tempting by the prospect it holds forth of exciting an extensive insurrection, but ruinous in the end, by exposing the patriotic forces to the risk of being beaten in detail.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.