This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Kosciuszko;s Revolt .

Introduction

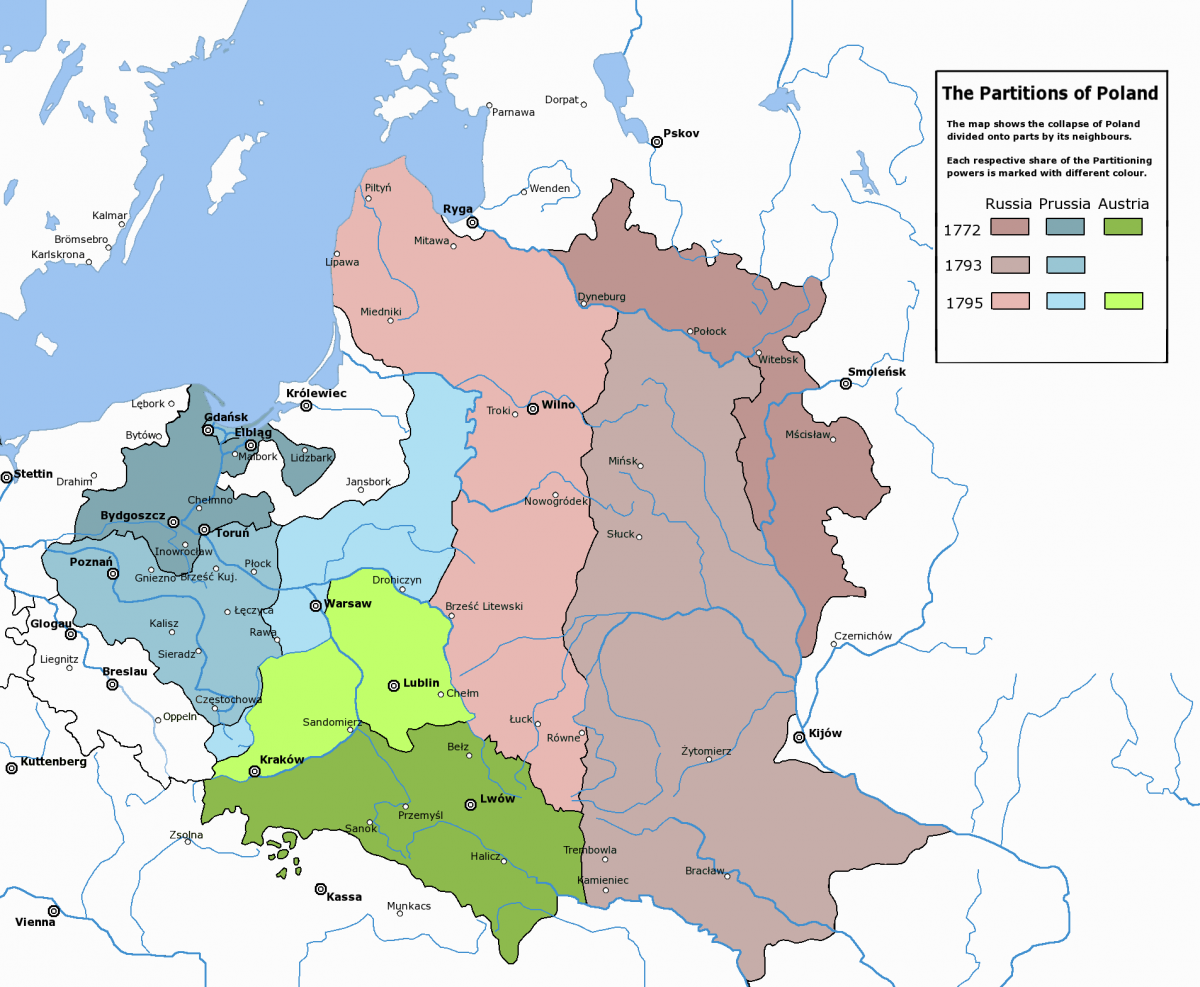

That the French Revolution was not more actively interfered with by the powers of Eastern Europe was largely due to the fact that they were all busy with a spoliation of their own. When Kosciuszko, the great Polish patriot and hero, failed in his endeavor to rescue his country from foreign thraldom, the doom of the ancient kingdom was sealed. In the following year (1795) the third and final partition of Poland — between Russia, Austria, and Prussia — was made. This destruction of a heroic nationality was bewailed by the friends of liberty throughout the world, and it was told in passionate regret how “Freedom shrieked, as Kosciuszko fell.”

Although brave and liberty-loving, the people of Poland had not kept pace with political progress among the more advanced nations. In the fourteenth century Poland had risen to her greatest power. Her political character, from ancient days, was peculiar, being at once monarchical and republican. But she had a feudalism of her own, which survived long after the European feudal system was outgrown by other nations. Her political system was cumbrous and lacking in unity. The first partition, by the powers above named (1772), left her in still worse disorder. A new constitution proved unsatisfactory, one party favoring it, another seeking to overthrow it. Russian interference was invoked, the Polish patriots resisted, but in 1792 they were defeated, and Russia, with Prussia, made the second partition of Poland in 1793.

In 1794 Kosciuszko was made commander-in-chief and dictator of Poland. The insurrection began with the murder of the Russians in Warsaw. But the Poles suffered from their own dissensions as before, and met with the disaster that led to their national extinction.

This selection is from History of Europe by Sir Archibald Alison published in 1854. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Sir Archibald Alison (1757-1839) was a Scottish Episcopalian priest and essayist.

Time: 1794

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

There is a certain degree of calamity which overwhelms the courage; but there is another, which, by reducing men to desperation, sometimes leads to the greatest and most glorious enterprises. To this latter state the Poles were now reduced. Abandoned by all the world, distracted with internal divisions, destitute alike of fortresses and resources, crushed in the grasp of gigantic enemies, the patriots of that unhappy country, consulting only their own courage, resolved to make a last effort to deliver it from its enemies. In the midst of their internal convulsions, and through all the prostration of their national strength, the Poles had never lost their individual courage, or the ennobling feelings of civil independence. They were still the redoubtable hussars who broke the Mussulman ranks under the walls of Vienna, and carried the Polish eagles in triumph to the towers of the Kremlin; whose national cry had so often made the Osmanlis tremble, and who had boasted in their hours of triumph that if the heaven itself were to fall they would support it on the points of their lances. A band of patriots at Warsaw resolved at all hazards to attempt the restoration of their independence, and they made choice of Kosciuszko, who was then at Leipsic, to direct their efforts.

[Thaddeus Kosciuszko was born in 1755, of a poor but noble family, and received the first elements of his education in the corps of cadets at Warsaw. There he was early distinguished by his diligence, ability, and progress in mathematical science, insomuch that he was selected as one of the four students annually chosen at that institution to travel at the expense of the State. He went abroad, accordingly, and spent several years in France, chiefly engaged in military studies; from whence he returned in 1778, with ideas of freedom and independence unhappily far in advance of his country at that period. As war did not seem likely at that period in the north of Europe, he set sail for America, then beginning the War of Independence, and was employed by Washington as his adjutant, and distinguished himself greatly in that contest beside Lafayette, Lameth, Dumas, and so many of the other ardent and enthusiastic spirits from the Old World. He returned to Europe on the termination of the war, decorated with the order of Cincinnatus, and lived in retirement till 1789, when, as King Stanislaus was adopting some steps with a view to the assertion of national independence, he was appointed major-general by the Polish Diet. In 1791 he joined with enthusiasm in the formation of the Constitution which was proclaimed on May 5th of that year. — ED]

This illustrious hero, who had received the rudiments of military education in France, had afterward served, not without glory, in the War of Independence in America. Uniting to Polish enthusiasm French ability, the ardent friend of liberty and the enlightened advocate for order, brave, loyal, and generous, he was in every way qualified to head the last struggle of the oldest republic in existence for its national independence. But a nearer approach to the scene of danger convinced him that the hour for action had not yet arrived. The passions, indeed, were awakened; the national enthusiasm was full; but the means of resistance were inconsiderable, and the old divisions of the Republic were not so healed as to afford the prospect of the whole national strength being exerted in its defense. But the public indignation could brook no delay; several regiments stationed at Pultusk revolted, and moved toward Galicia; and Kosciuszko, albeit despairing of success, determined not to be absent in the hour of danger, hastened to Cracow, where on March 3rd he closed the gates and proclaimed the insurrection.

Having, by means of the regiments which had revolted, and the junction of some bodies of armed peasants — imperfectly armed, indeed, but full of enthusiasm — collected a force of five thousand men, Kosciuszko left Cracow, and boldly advanced into the open country. He encountered a body of three thousand Russians at Raslowice, and, after an obstinate engagement, succeeded in routing it with great slaughter. This action, inconsiderable in itself, had important consequences; the Polish peasants exchanged their scythes for the arms found on the field of battle, and the insurrection, encouraged by this first gleam of success, soon communicated itself to the adjoining provinces. In vain Stanislaus disavowed the acts of his subjects; the flame of independence spread with the rapidity of lightning, and soon all the freemen in Poland were in arms. Warsaw was the first great point where the flame broke out. The intelligence of the success at Raslowice was received there on April 12th and occasioned the most violent agitation. For some days afterward it was evident that an explosion was at hand; and at length, at daybreak on the morning of the 17th, the brigade of Polish guards, under the direction of their officers, attacked the governor’s house and the arsenal, and was speedily joined by the populace. The Russian and Prussian troops in the neighborhood of the capital were about seven thousand men; and after a prolonged and obstinate contest in the streets for thirty-six hours, they were driven across the Vistula with the loss of above three thousand men in killed and prisoners, and the flag of independence was hoisted on the towers of Warsaw.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.