Today’s installment concludes Poland’s Downfall,

our selection from History of Europe by Sir Archibald Alison published in 1854.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Poland’s Downfall.

Time: 1795

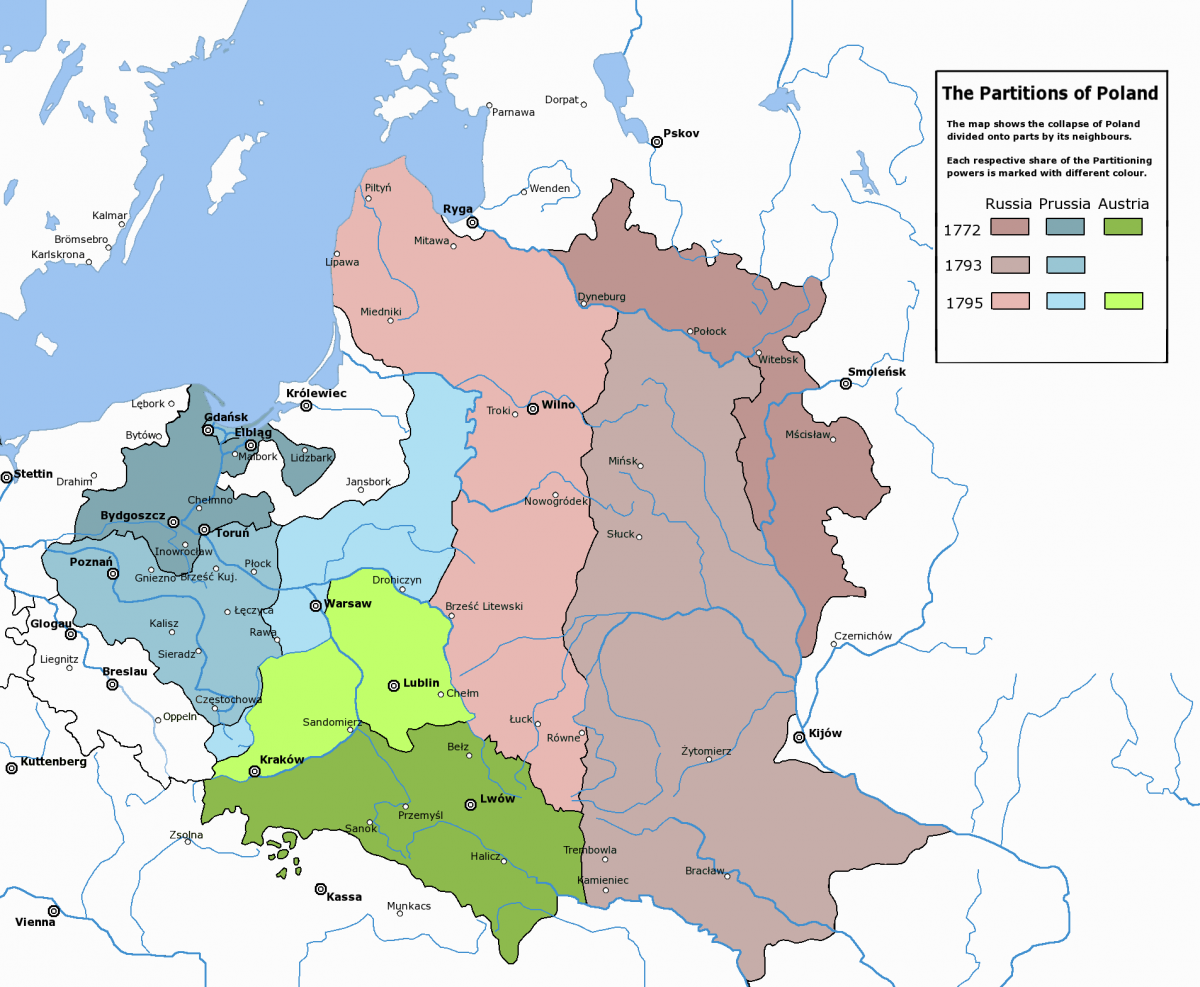

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Scarcely had the Poles recovered from their intoxication at the raising of the siege of Warsaw when intelligence was received of the defeat of Sizakowsky, who commanded a corps of ten thousand men beyond the Bug, by the Russian grand army under Suvaroff. This celebrated General, to whom the principal conduct of the war was now committed, followed up his successes with the utmost vigor. The retreating column was again assailed on the 19th by the victorious Russians, and after a glorious resistance driven into the woods between Janoff and Biala, with the loss of four thousand men and twenty-eight pieces of cannon. Scarcely three thousand Poles, with Sizakowsky at their head, escaped into Siedlice.

Upon receiving the accounts of this disaster, Kosciuszko resolved, by drawing together all his detachments, to fall upon Fersen before he joined Suvaroff and the other corps which were advancing against the capital. With this view he ordered General Poninsky to join him, and marched with all his disposable forces to attack the Russian General, who was stationed at Maccowice; but fortune on this occasion cruelly deceived the Poles. Arrived in the neighborhood of Fersen’s position he found that Poninsky had not yet come up; and the Russian commander, overjoyed at this circumstance, resolved immediately to attack him. In vain Kosciuszko despatched courier after courier to Poninsky to advance to his relief. The first was intercepted by the Cossacks, and the second did not reach that leader in time to enable him to take a decisive part in the approaching combat. Nevertheless the Polish commander, aware of the danger of retreating with inexperienced troops in presence of a disciplined and superior enemy, determined to give battle on the following day, and drew up his little army with as much skill as the circumstances would admit.

The forces on the opposite sides in this action, which decided the fate of Poland, were nearly equal in point of numbers; but the advantages of discipline and equipment were decisively on the side of the Russians. Kosciuszko commanded about ten thousand men, a part of whom were recently raised and imperfectly disciplined; while Fersen was at the head of twelve thousand veterans, including a most formidable body of cavalry. Nevertheless, the Poles in the centre and right wing made a glorious defense; but the left, which Poninsky should have supported, having been overwhelmed by the cavalry under Denisoff, the whole army was, after a severe struggle, thrown into confusion. Kosciuszko, Sizakowsky, and other gallant chiefs in vain made the most heroic efforts to rally the broken troops. They were wounded, struck down, and made prisoners by the Cossacks who swarmed over the field of battle; while the remains of the army, now reduced to seven thousand men, fell back in confusion toward Warsaw.

After the fall of Kosciuszko, who sustained in his single person the fortunes of the Republic, nothing but a series of disasters overtook the Poles. The Austrians, taking advantage of the general confusion, entered Galicia, and occupied the palatinates of Lublin and Sandomir; while Suvaroff, pressing forward toward the capital, defeated Mokronowsky, who, at the head of twelve thousand men, strove to retard the advance of that redoubtable commander. In vain the Poles made the utmost efforts; they were routed with the loss of four thousand men; and the patriots, though now despairing of success, resolved to sell their lives dearly, and shut themselves up in Warsaw to await the approach of the conqueror. Suvaroff was soon at the gates of Praga, the eastern suburb of that capital, where twenty-six thousand men and one hundred pieces of cannon defended the bridge of the Vistula and the approach to the capital. To assault such a position with forces hardly superior was evidently a hazardous enterprise; but the approach of winter, rendering it indispensable that if anything was done at all it should be immediately attempted, Suvaroff, who was habituated to successful assaults in the Turkish wars, resolved to storm the city. On November 2d the Russians made their appearance before the glacis of Praga, and Suvaroff, having in great haste completed three powerful batteries and breached the defenses with imposing celerity, made his dispositions for a general assault on the following day.

The conquerors of Ismail advanced to the attack in the same order which they had adopted on that memorable occasion. Seven columns at daybreak approached the ramparts, rapidly filled up the ditches with their fascines, broke down the defenses, and pouring into the intrenched camp carried destruction into the ranks of the Poles. In vain the defenders did their utmost to resist the torrent. The wooden houses of Praga speedily took fire, and amid the shouts of the victors and the cries of the inhabitants the Polish battalions were borne backward to the edge of the Vistula. The multitude of fugitives speedily broke down the bridges; and the citizens of Warsaw beheld with unavailing anguish their defenders on the other side perishing in the flames, or by the sword of the conquerors. Ten thousand soldiers fell on the spot, nine thousand were made prisoners, and above twelve thousand citizens, of every age and sex, were put to the sword — a dreadful instance of carnage which has left a lasting stain on the name of Suvaroff and which Russia expiated in the conflagration of Moscow. The tragedy was at an end. Warsaw capitulated two days afterward; the detached parties of the patriots melted away, and Poland was no more. On November 6th Suvaroff made his triumphant entry into the blood-stained capital. King Stanislaus was sent into Russia, where he ended his days in captivity, and the final partition of the monarchy was effected.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Poland’s Downfall by Sir Archibald Alison from his book History of Europe published in 1854. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Poland’s Downfall here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.