This series has two easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Miguel Grau, Hero .

Introduction

When the Monitor and the Merrimac fought their celebrated battle in 1862 they made obsolete forever all the war-vessels of antiquity. Iron superseded wood. Engines superseded sail. The first ironclads, however, were not sea-going ships. They fought better than they floated and while of inestimable value for the defense of a harbor, they were worthless for cruising. The inventors of the entire world, in Europe as well as in America, set at once to work to remedy this defect and the next decade saw a further revolution in the construction of fighting-ships. The cumbrous rams of the Merrimac type, the unseaworthy imitations of the Monitor, gave place to swift, alert, and almost unsinkable metallic ships, which are the pride of navies and the burden of taxpayers today.

The construction of these huge monsters was continued for some time on lines merely theoretical. As they never had been employed in actual battle, no one knew how they would succeed in the practical, final test of attack and resistance. Their first trial came in 1879, in the war between Peru and Chile.

At the outset of this war each of the contestants was the proud possessor of two modern, European-built ironclads, those of Chile being the newer and stronger. Both sides possessed also a number of wooden vessels. A few of the latter, venturing north from Chile, were attacked by the Peruvian ironclads and overwhelmed. But in the course of the pursuit the larger Peruvian ship, the pride of the nation, the Independencia, ran upon a shoal and was wrecked.

This left the smaller Peruvian ironclad, the Huascar, the sole protector of her country against the Chilean fleet. The story of her final fight, with all the vastly important lessons in naval construction which were drawn therefrom, is here narrated by Mr. Markham, the well-known English historian of the entire war.

This selection is from War Between Peru and Chile by Clements R. Markham published in 1882. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Clements R. Markham (1830-1916) was an English geographer, explorer, and writer. He was President of the Royal Geographic Society for twelve years.

Time: October 8, 1879

Place: Punta Angamos

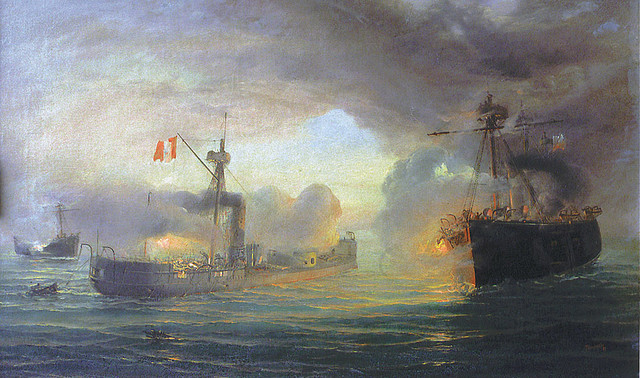

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The career of the Peruvian battleship Huascar, after the loss of her consort — when, single-handed, she long eluded the chase of two Chilean ironclads, each more powerful than herself, and kept the enemy in a state of constant alarm — is the most interesting episode of the naval war in the Pacific, a war of which Miguel Grau is the hero.

This man was the son of a Colombian officer, whose father was a merchant at Cartagena. The name indicates Catalonian ancestry. A descendant of that race of sturdy seamen which long lorded it in the Mediterranean was now to win undying fame in the Pacific. The father, Juan Miguel Grau, came to Peru with General Bolivar, and was a captain at the Battle of Ayacucho. His comrades returned to Colombia in 1828; but the attractions of a fair Peruvian induced the elder Grau to settle at Piura, and there young Miguel was born, in June, 1834. The child was named for the patron saint of his native town. His father held some post in the Payta custom-house, but he does not appear to have been in good circumstances, for his son was shipped on board a merchant-vessel at Payta at the age of ten. He knocked about the world as a sailor-boy, learning his profession thoroughly by hard work before the mast for the next seven years, and it was not until he was eighteen that he obtained an appointment as midshipman in the very humble navy of Peru. He was on board the Apurimac when Lieutenant Montero mutinied in the roadstead of Arica against the Government of Castilla and declared for his rival Vivanco. The friendless mid shipman probably had no choice but to obey orders and follow the fortunes of the insurgents until the downfall of their leader; besides, Montero was a fellow-townsman, being also a native of Piura. As soon as the rebellion was suppressed, in 1858, Grau once more returned to the merchant service, and traded to China and India for about two years.

Miguel Grau was now one of the best practical seamen in Peru, well known for his ability, readiness of resource, and courage, as well as for his genial and kindly disposition. When, therefore, he rejoined the navy in 1860, he at once received command of the steamer Lersundi, and soon afterward he was sent to Nantes with the duty of bringing out two new corvettes.

He attained the rank of full captain in 1868, and commanded the Union for nearly three years, and afterward the Huascar, the turret-ship on board which he won his deathless fame. In 1875 he was a Deputy in Congress for his native town and was an ardent supporter of the Government of Don Manuel Pardo. He visited Chile in 1877, was at Santiago, and for a short time at the baths of Cauquenes. The object of this visit was to bring the body of his father, who had died at Valparaiso, to Piura, to be buried beside his mother. When the war broke out he had completed twenty-nine years of service in the Peruvian navy, and was Member of Congress for Payta. Admiral Grau had married a Peruvian lady of good family, Dona Dolores Cavero, who, while mourning her irreparable loss, found some consolation in the way the services of her gallant husband were appreciated.

The last great sacrifice for that country, now in her utmost need, was about to be made. On October 1st a squadron, consisting of two ironclads and several other vessels, all carefully and thoroughly refitted, was dispatched from Valparaiso for the purpose of forcing the Huascai to fight, single-handed, against hopeless odds. This fleet first visited Arica, and there it was ascertained on October 4th that the Huascar, in company with the Union, was cruising to the southward. The speed of the Chilean ironclads was superior to that of the Huascar.

The Chilean Admiral ordered his fastest ships — the Cochrane, under Captain Latorre, with the O’Higgins and the Loa — to cruise from twenty to thirty miles off the land, between Mexillones Bay and Cobija, while he himself in the Blanco, with the Covadonga and the Matias Cousino, vessels of inferior speed, pa trolled the coast between Mexillones and Antofagasta. Thus the fleet was posted in such a manner as to intercept all vessels proceeding to the northward, unless they had previously been made acquainted with the disposition of the Chilean ships.

The Peruvian Government had recognized the energy and gallantry of Don Miguel Grau since he had commanded the Huascar, by advancing him to the rank of Rear- Admiral ; while the ladies of the town of Truxillo, in the northern part of Peru, as a further reward for his great services, had presented him with a handsomely embroidered ensign, made by their own hands.

The Huascar and the Union were cruising together in the vicinity of Antofagasta, watching the Chilean vessels in that port, and doing their utmost to impede the military preparations for the invasion of Peru. Early in the morning of October 8th, in total ignorance of the proximity of his enemies, Grau steamed quietly to the northward, closely followed by the Union. The weather was thick and foggy, as is not unusual on the coast at that time of the year. As the dawn broke, the fog lifted slightly, and they were able to make out three distinct jets of smoke appearing on the horizon immediately to the northeast and close under the land near Point Angamos. This is the western extreme of Mexillones Bay. Admiral Grau at once suspected that these jets of smoke could proceed from no other funnels than those of the hos tile vessels that were in pursuit of him. He signaled the presence of the enemy to his consort, steered to the westward for a short distance, trusting to what he believed to be the superior speed of his two ships for the means of escape, and then hauled up to the northwest. Soon the light enabled him to recognize the Chilean ironclad Blanco, the sloop Covadonga, and the transport Matias Cousino. All was going well for the Peruvian ships, which appeared to be gradually but surely increasing the distance from their pursuers, when, at 7:30 a.m., three more jets of smoke came in sight, in the very direction in which they were steering. It was soon discovered that they were issuing from the funnels of the ironclad Cochrane, the O’Higgins, and the Loa.

Grau’s situation now became critical in the extreme. Escape was barred in every direction and soon it became evident that the advancing Chilean ironclad would intercept the Huascar before she could cover the distance between her position and safety.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.