This series has six easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: After the Germans Left Paris.

Introduction

Immediately following the Franco-Prussian War occurred a crisis in France that precipitated a new reign of terror. This was the uprising of the Commune in Paris against the authority of the Assembly-the legislative body of the Third Republic. After the conclusion of preliminary peace agreement between Prussia and France (March 2, 1871), Paris was abandoned by nearly all the ruling and influential men. Those who remained in the city — ]ules Favre, Ernest Picard, and Jules Ferry-were unpopular and left the direction of affairs to Generals Vinoy and Pala dines. Paris was filled with unrest and apprehension. It was rumored that the Republic was threatened with a coup d’état, and Paris with the entrance of the Germans. The walls of the city were placarded with calls to resistance. The actual entry of German troops (March 1st), in accordance with the preliminaries of peace, was declared by Thiers to be one of the principal causes of the insurrection.

The revolutionaries embraced several parties — Blanquists, followers of Louis Blanqui, traditional insurrectionists ; the later Jacobins, violent partisans of a strong republican government; socialists of various schools; and the International or workingmen’s party. These were the chief elements that formed the politico-social body known as the Commune of Paris, which had its precursor in the revolutionary committee of 1789-1794, also called the Commune. The city was full of idle persons, among whom were many of the more than two hundred fifty thousand soldiers just released from active service; a great influx came from the provinces ; fragments of the army of Garibaldi in the late war gathered and below all others was “ a nameless collection ” of the criminal population. Arms were plentifully supplied for the rising, and the streets were barricaded. How far the National Guard could be trusted by the Assembly no man could tell. It mainly went over to the Commune.

Such was the condition of Paris after the withdrawal of the German troops from the city (March 3d). At this point begins the narrative of Hanotaux, the noted French statesman and historian, who has made valuable additions to our knowledge of these exciting events.

This selection is from Histoire de la France contemporaine by Gabriel Hanotaux published in 1903. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Gabriel Hanotaux (1853-1944) was a French historian and statesman.

Time: 1871

Place: Paris

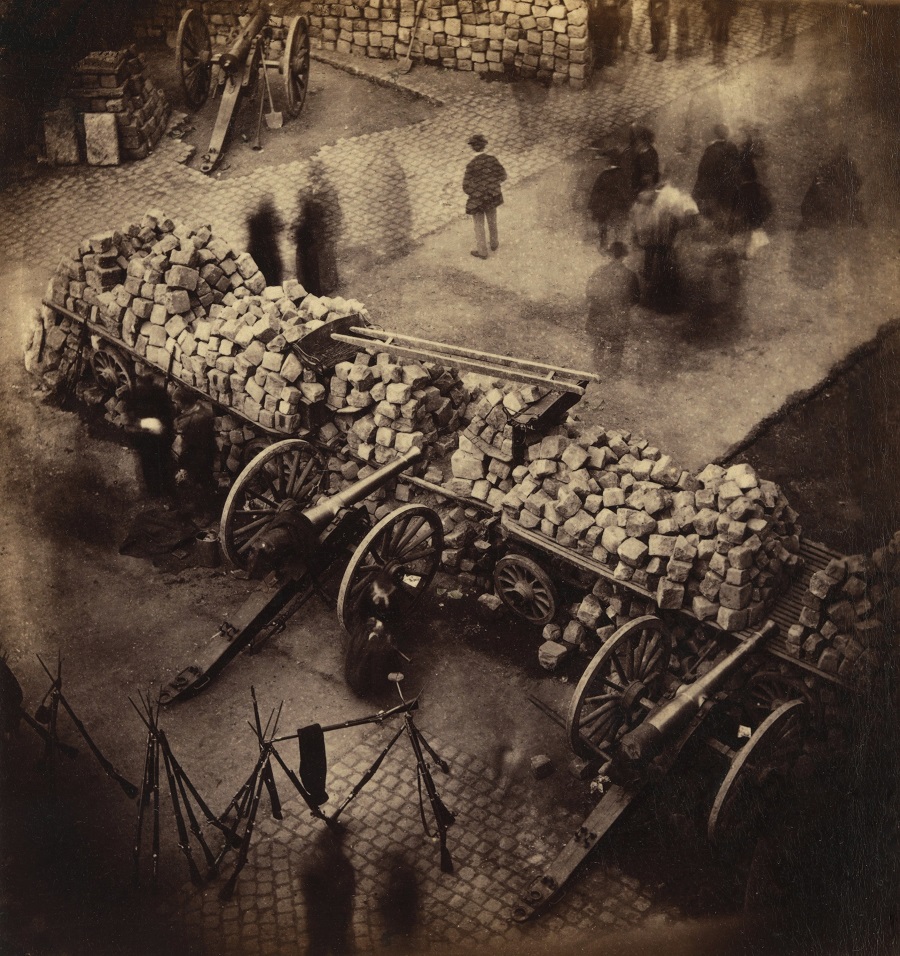

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

After the foreign troops left Paris, fifteen days passed away in alternations of fear and hope. The question of the government was raised at Bordeaux, the question of disarmament at Paris. A conclusion was necessary. Both sides made their preparations.

On March 8th Duval, the future general of the Commune, established an insurrectional section at the Barrier d’Italie, and organized for resistance. The Central Committee approached the International. Meanwhile M. Jules Ferry, Mayor of Paris, was still writing to the Government on March 5th: “The city is calm; the danger is over. At the bottom of the situation here, great weariness, need of resuming the normal life: but no lasting order in Paris without government or assembly. The Assembly returning to Paris can alone reestablish order, consequently work which Paris so much needs; without that, nothing possible. Come back quickly.”

Then came the news relative to the law of debts and the question of rents, to the transference of the Assembly to Versailles; it was affirmed that a coup d’etat was in preparation. M. Thiers, head of the Provisional Government, installed himself, March 15th, at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The moment had come to act. It was necessary to proceed to disarmament. Paris could not be left thus, beside herself, rifle in hand.

The knot was at Belleville and Montmartre. A council of ministers was called on the 17th at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The subject of deliberation was the opportuneness of a stroke on the part of authority which was defined in this formula: “Recover the guns.” * M. Thiers says: “The general opinion was in favor of recovering the guns.” He says again: “An opinion in favor of immediate action was universally pronounced.” He says again: “Many persons, concerning themselves with the financial question, said that we must after all think of paying the Prussians. The businessmen went about everywhere repeating: ‘You will never do anything in the way of financial operations unless you finish with this pack of rascals, and take the guns away from them. That must be done with, and then you can treat of business.” And he concludes: “The idea that it was necessary to remove the guns was dominant, and it was difficult to resist it. In the situation of men’s minds, with the noises and rumors that circulated in Paris, inaction was a demonstration of feebleness and impotence.”

[* Many cannon had been removed to these places by the National Guard and the Commune.—ED.]

The stroke was decided on; it consisted in bringing into the interior of Paris the guns that were guarded on the heights of Montmartre. There were at most twenty thousand troops of the Assembly to execute the plan.

It was arranged that action should begin at two o’clock in the morning. M. Thiers was at the Louvre, anxious, with General Vinoy, who answered for success. The operation seemed at first to be succeeding. General Lecomte occupied the plateau. The whole hill was surrounded. But a large number of teams would have been necessary to operate such a colossal removal before daybreak. The teams were not there; the army had no longer any horses. Several days were necessary to take away all the guns. Then it was seen that the operation was badly planned. However, seventy guns were carried off and the remainder were guarded by troops, waiting with grounded arms.

Little by little the news that the guns were being taken away spread in Montmartre. The alarm-bell was rung. Some shots were fired and roused the quarter. The eminence and surround ing regions were astir. There was a shout of “Coup d’etat1″ The National Guards assembled. The crowd of women and children pushed around the soldiers who were guarding the guns. “Hurrah for the Linel” they cry on all sides. “You are our brothers; we do not wish to fight you.” They penetrate into the ranks of the soldiers, offer them drink, disarm them. They hold up the stocks of their rifles, disbanding themselves. General Lecomte was surrounded and taken prisoner, along with his staff.

M. Thiers returned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. At the Hotel de Ville, where the Mayor of Paris, M. Jules Ferry, remained permanently on duty, they waited for news. At first it was good; then it was worse; at half-past ten the disaster was defined; the head police-office telegraphed: “Very bad news from Montmartre. Troops refused to act. The heights, the guns, and the prisoners retaken by the insurgents, who do not appear to be coming down. The Central Committee should be at the park in the Rue Basfroi!”

At the Ministry of Foreign Affairs the Government sat in permanence in the great gallery that looks upon the garden and over the quay. Men bringing news come in and go out. The generals deliberate in a corner,

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.