A violent wind arose; it came from the south, and spread the flames, the smoke, the horror of the immense conflagration in a squall of fire toward the west

Continuing The 1871 Paris Commune,

our selection from Histoire de la France contemporaine by Gabriel Hanotaux published in 1903. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The 1871 Paris Commune.

Time: 1871

Place: Paris

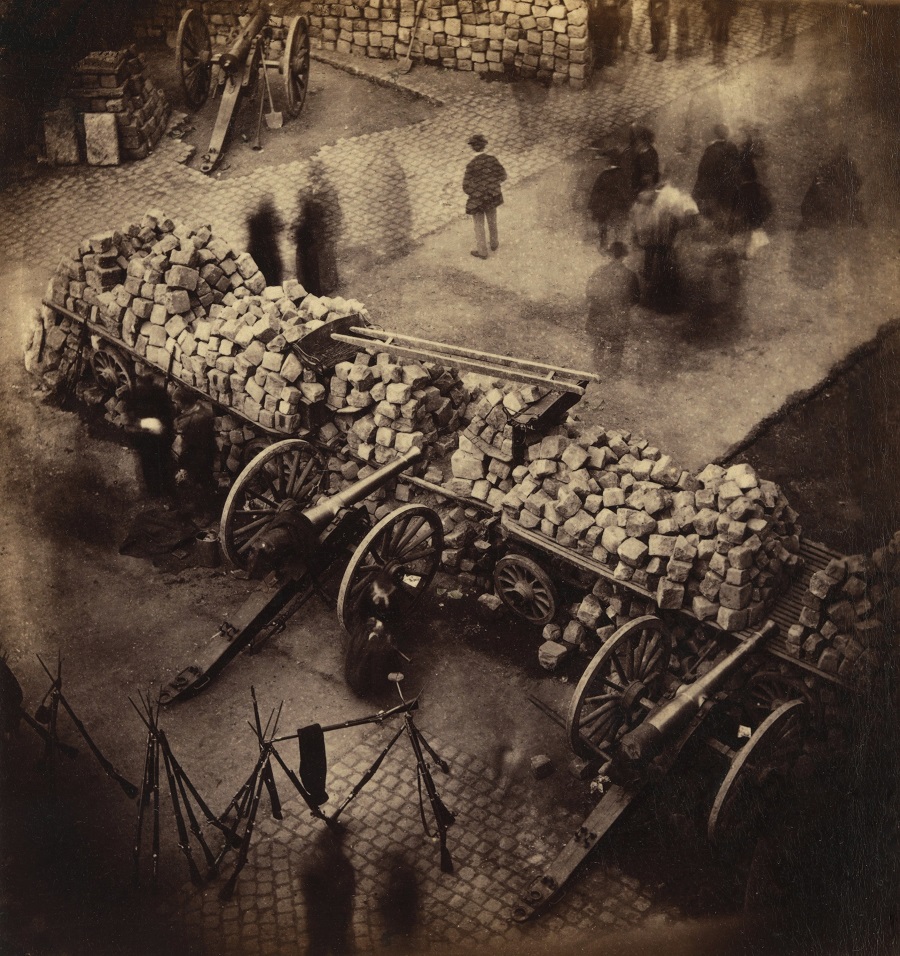

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

When night came, Brunel abandoned the Rue Royale. At three o’clock in the morning Bergeret blew up the Tuileries. Notre-Dame and the Hotel-Dieu were saved only by the courage of the staff of the hospital, led by M. Brouardel. Everything was burning; explosions were everywhere. It was a night of terror. The Porte Saint-Martin, the church of Saint-Eustache, the Rue Royale, the Rue de Rivoli, the Tuileries, the Palais Royale, the Hotel de Ville, the left bank from the Legion d’Honneur to the Palais de Justice and the Police Office were immense red braziers, and above all rose lofty blazing columns. From outside, all the forts were firing upon Paris. Inside Paris, Montmartre, now in the hands of the Versailles troops, was firing upon Pere la Chaise; the Point-du-Jour upon the Butte-aux-Cailles, which returned the fire. The gunners were cannonading one another across the town and above the town. Shells fell in every direction. All central quarters were a battlefield. It was a chaos; bodies and souls in collision over a crumbling world.

The night was dark, the sky black; a violent wind arose; it came from the south, and spread the flames, the smoke, the horror of the immense conflagration in a squall of fire toward the west, toward the enemy, toward Versailles, and toward those slopes of Saint-Cloud from the heights of which the members of the Government, the members of the Assembly, came to look on at a catastrophe in which the city was on the point of sinking.

M. Thiers had returned to Paris on Monday, the 22nd, at three o’clock in the morning, by the Point-du-Jourgate. M. Jules Ferry, Mayor of Paris, had accompanied the first battalion of infantry, which, following the left bank, had occupied the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, just quitted by M. Pascal Grousset. Here was the seat of government; here Marshal MacMahon established his headquarters. M. Thiers, however, maintained constant relations with the National Assembly, which continued to sit at Versailles.

Prisoners were already coming in. But the Commune was not yet defeated. In the city all the furies were unchained. In the course of a deadly struggle, in which all minds appeared to lose their balance, the blood frenzy became universal. The most hideous rumors spread abroad; the soldiers were being murdered, were being poisoned; the firemen were putting petroleum in their engines. Then it was affirmed that the Commune, in a last convulsion of its rage, had assassinated the hostages.

In fact, on Wednesday, the 24th, in one quarter, police agents, prisoners, were shot in cold blood at Sainte-Pélagie by order of the pretended revolutionary tribunal presided over by Raoul Rigault. At La Roquette, in the night between the 24th and 25th, on the written order of Fen‘é, transmitted by Genton, a magistrate of the Commune, a squad commanded by a Fédérate captain, Vérig, massacred Georges Darboy, Archbishop of Paris, Abbé Deguerry, Fathers Clerc, Ducoudray, and Allard, and M. Bonjean. Death was everywhere. On both sides henceforth the word of command was to be, “No quarter.” On the same day, at ten o’clock in the morning, fifteen members of the Commune met at the Hotel de Ville and determined to burn it down. The fire was started in the roof, and soon the ancient municipal building was in flames.

On the 25th, Thursday, the new line of defense was at the bridge of Austerlitz, resting on Mazas. Another siege began and a second assault had to be made. The troops were exhausted. But the last combatants were resolved to perish. Women and children were on the barricades and delivered fire. A strange frenzy excited these brave but feeble beings, and they continued to struggle after the men had left the barricades. At Mazas the civil prisoners revolted. At the Avenue d’Italie the Dominicans of Arcueil and their servants were killed by National Guards of the 101st Fédérate battalion, commanded by Serizier.

Meanwhile the bridge of Austerlitz was carried. The Butte aux-Cailles, where Wroblewski resisted with energy, was occupied. The whole left bank was taken as far as the Orléans station. Fighting was still going on at the Chateau-d’Eau and the Bastille. The Place de la Bastille was turned by way of the Vincennes railway. All the survivors of the struggle, the desperates, met at the town hall of the Eleventh Ward, on the Boulevard Voltaire, around Delescluze, who was still obeyed; Vermorel on horseback, wearing the red scarf, was visiting the barricades, encouraging the men, seeking and bringing in reinforcements. At midday twenty-two members of the Commune and the Central Committee met, and Arnold informed them of the proposal of Mr. Washburne, Minister of the United States, suggesting the mediation of the Germans. Delescluze lent himself to this negotiation; he wished to make for the Vincennes gate, but he was repulsed by the Fédérates, who accused him of desertion. He came back, returned to the town hall, and wrote a letter of fare well to his sister.

Toward seven o’clock in the evening Delescluze set out, ac companied by Jourde and about fifty Fédérates, marching in the direction of the Place du Chateau-d’Eau. Delescluze was dressed correctly — silk hat, light overcoat, black frock-coat and trousers, red scarf round the waist, as he used to wear it; he was distinguished by his neat civilian costume from his company with their tattered uniforms. He had no arms and supported himself on a walking-stick. He met Lisbonne, wounded, who was being carried in a litter, then Vermoral, wounded to death, held up by Chièze and Ayrial. Delescluze spoke to him and left him. The sun was setting behind the square. Delescluze, without looking to see whether he was being followed, went on at the same pace, the only living being on the pavement of the Boulevard Voltaire. He had only a breath left, his steps dragged. Arriving at the barricade he turned to the left and climbed the paving-stones. His face was seen to appear with its short white beard, then his tall figure. Suddenly he disappeared. He had just fallen, stricken to death.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.